Promises made during election campaigns that are later dropped for political expediency are broken promises.

Those are wise words for both the Obama Administration and the FCC as they ponder what to do about broadband regulation. President Obama campaigned on developing an effective National Broadband Plan and preserving the integrity of the Internet with Net Neutrality policies. Both will now be tested in how they respond to a recent court decision which has thrown a wrench into broadband policy initiatives. At issue:

- How Americans access the Internet;

- What kind of Internet they find once they access it;

- How much money is it going to cost at the end of the month for what kind of service.

These are all laid on the table of FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski with a big bow attached, courtesy of Comcast. The nation’s largest cable company threw a hissyfit when the FCC rebuked them for throttling the speeds of their Internet customers. They sued and won more than they bargained for when the DC District Court ruled the Commission lacked the authority to regulate broadband as an “information service,” a dubious premise cooked up by former FCC chairman Michael Powell. The concept was akin to a police officer placing you under arrest on the authority of a bottle of green tea. Of course you could get away with that too as long as nobody challenged it in court.

Chairman Genachowski could choose to kick the ball down the field to be played another day by appealing the court decision or trying to get Congress to pass new legislation. Or he can strike decisively and effectively by declaring broadband to be what it actually is — a “telecommunications service.” Under that declaration, the FCC can implement its National Broadband Plan, which will dramatically improve access for rural America and promote better broadband service for those who already have it. The Commission can also move forward on common sense Net Neutrality policies that tell providers not to interfere with online traffic for monetary reasons. It can even give the Commission the authority to keep a watchful eye for the next clever scheme that benefits providers at the customer’s expense.

But that depends on Chairman Genachowski standing up to the broadband industry, their friends in Congress, and the inevitable industry-funded BS Festival from astroturfers designed to sucker people into supporting industry positions.

The threats and concern trolling are already parading across the Beltway:

- “The industry would declare war on the FCC“: That war has been underway ever since the litigious broadband industry first started running to friendly courts whenever it encountered a regulatory nuisance just waiting to be overturned on “free speech for corporations”-grounds. Chairman Genachowski needs to borrow from President George W. Bush and declare, “bring ’em on!” He can fight industry propaganda about “lost jobs” and “investment” with facts found in every provider’s quarterly financial reports showing bountiful harvests of profits, while spending and costs decline. It’s not the FCC’s fault Verizon fired more than 13,000 employees in the past few years. The FCC didn’t tell Verizon to stop upgrading its copper wire network to fiber optics to remake traditional landline phone service into something far better and eventually even more profitable.

- “Congress would be upset by an overreaching Obama Administration”: That would mostly be the same Republican members who reflexively oppose every aspect of the Obama Administration’s legislative agenda. Considering warmed-over health care reform is still being called “socialist” and an “apocalypse” by these people, there isn’t a Pick-Me-Up Bouquet in the world that could get them to support this administration. Ordering a ham sandwich and leaving the Swiss cheese off would probably result in some members of Congress reciting Glenn Beck’s declaration the omission is proof Obama is working with lactose-intolerant high officials of the Chinese Communist regime.

- “Verizon, AT&T, and others will step up spending on Astroturf Campaigns”: If a consumer like myself can sniff out an industry-funded campaign to convince consumers to support policies directly challenging their own wallets, why can’t Washington policymakers? The industry talking points rarely change anyway, and those shouting the loudest usually try to obscure who paid for the megaphone. When in doubt, simply ask “is there any industry money funding your organization?” If they won’t say, you have your answer.

- “But they’ll sue”: When are they not suing? Of course the industry will challenge the legality of any policy that puts their quest for unlimited profits at a disadvantage. We live in a system of checks and balances between private enterprise and public oversight and regulation. The struggle for the perfect balance between the two will persist forever, but after an era of reckless deregulation and abdicated oversight responsibility, the resulting Great Recession should provide strong evidence the pendulum needs to swing in the opposite direction.

USA Today today published a piece on Genachowski’s coming decision which hit all the aforementioned bases.

Astroturf Campaigns and Legal Threats: “If the FCC changes the way it treats high-speed Internet, then “everybody in the industry would sue,” says Scott Cleland, chairman of NetCompetition.org, an Internet forum supported by cable and phone companies. “It would be like an 8.0 earthquake under the sector,” he adds. “Hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested (in broadband) in the belief that there’d be a market rate of return, not a regulated rate.”

Cleland is a notorious industry mouthpiece, but at least he openly acknowledges his strings are pulled by the industry that generously funds his anti-consumer, pro-provider rhetoric.

Republicans: The FCC’s two Republican commissioners have said they’d fight a move to reclassify broadband.

No surprises there, and you can expect most Republicans in Congress to also take the industry’s position on these matters. Guess what? They still won’t vote for you even if you compromise with the broadband industry.

USA Today, itself headquartered in suburban Washington, delivers up the beltway solution always pressed on pliable Democrats – compromise away your principles and split the difference:

If Genachowski wants to defuse the issue, he could try to engineer a compromise. For example, he could agree to take broadband reclassification off the table as long as providers make legally binding promises to offer consumer protections called for in the National Broadband Plan and to agree to treat all Web services equally. But it will be hard to please everybody as advocates gear up for a fight.

That’s the understatement of the year. It’s also a classic case of reinventing the wheel. What USA Today‘s reporter suggests is exactly what the FCC used prior to the Comcast case to regulate broadband — an “understanding” with the industry without clear-cut regulatory authority. That lasted until the three judge panel laughed it out of court. The FCC has no authority in its current form to make legally binding promises with an industry that contemptuously dismisses the notion it should have any in the first place. Without reclassification, the judge certain to hear the next court case challenging the “understanding” will almost certainly throw that out as well.

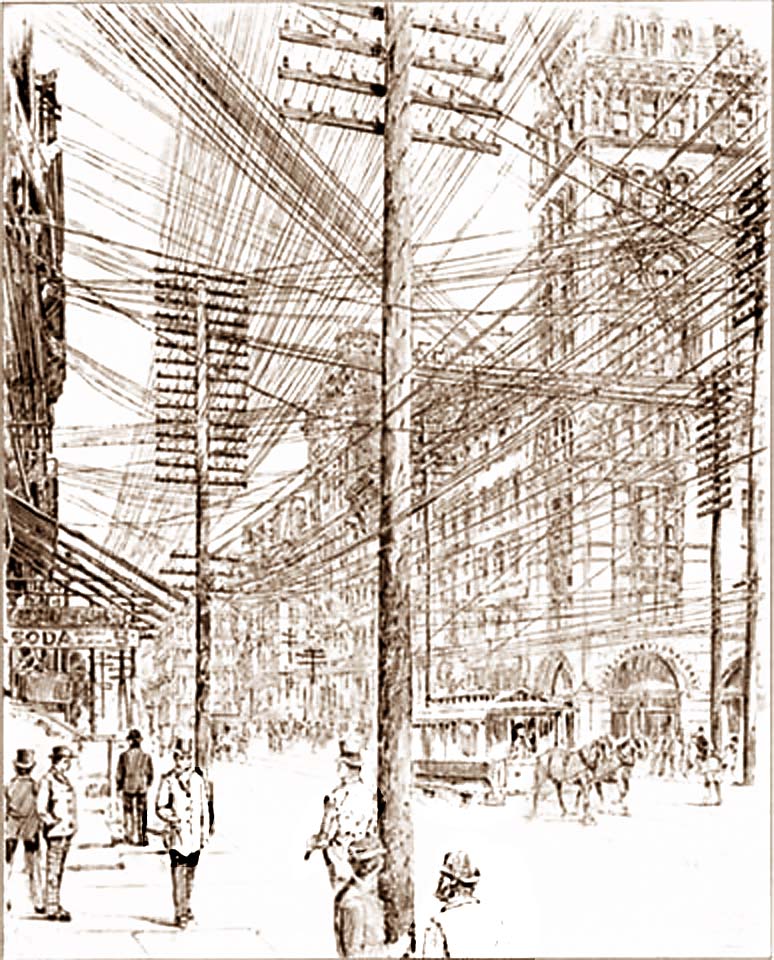

Declaring regulatory authority does not, as the industry likes to pretend, mean that your Internet Service Provider will be saddled with 1930s telephone rules. It merely gives the FCC the authority to move forward on its agenda to improve broadband, protect its integrity, and help coordinate a plan for the future that first takes your interests to heart, not simply those on Wall Street.

For a change of pace, let’s choose the clearly marked road of reclassification and avoid the deregulatory dead end of broken promises offered by the broadband industry or the equally awful decision to build a new road in a futile effort to win bipartisan brownie points.

[Article Correction 4/15/2010: The original piece laid blame for the classification of broadband as an “information service” on former FCC Chairman Kevin Martin. In fact, the classification was made by former FCC Chairman Michael Powell, who served during the first term of the Bush Administration. We regret the error.]

Subscribe

Subscribe