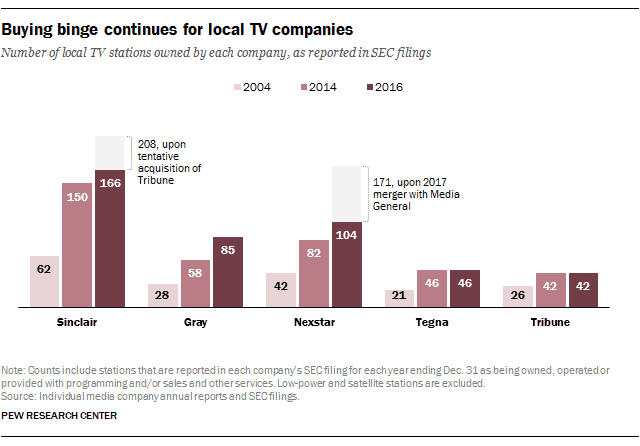

Along with a new TV season starting this fall, the Federal Communications Commission plans to launch a new season of sweeping deregulation in the broadcasting industry, allowing a handful of companies to acquire masses of local TV stations as a result of easing ownership limits.

Bloomberg News reports FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, with likely support from fellow Republican commissioner Mike O’Rielly, will unveil new rules that will allow TV station owners like Nexstar, Tegna, E.W. Scripps, and Meredith to acquire dozens of local stations, even in cities where they already own stations.

The new rules, likely to pass on a party line vote, would allow companies to own two of the four most-viewed stations in a market, in addition to several other lesser-rated outlets. Broadcasters are also heavily lobbying Republicans to insert another new rule that would lift the current ban on owning both the local daily newspaper and a TV station.

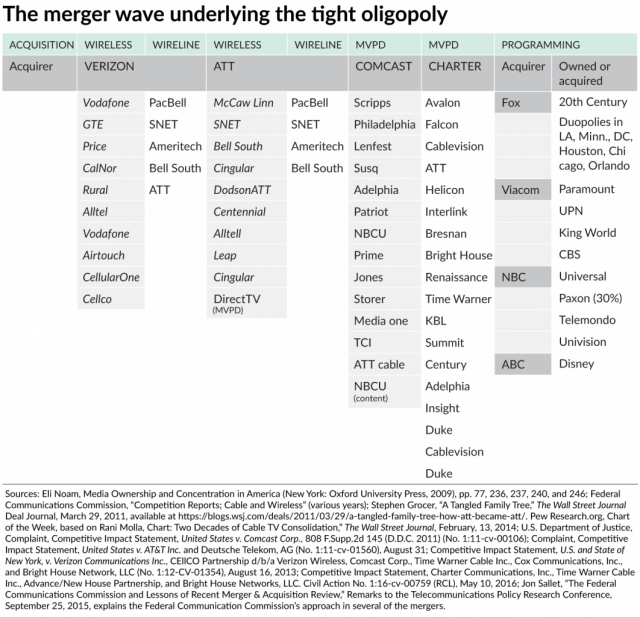

Broadcasters have been itching to launch a sweeping wave of station ownership consolidation to boost advertising revenue, cut costs, and gain more leverage over cable and satellite companies as they continue to raise fees charged for consent to carry those stations on pay television lineups.

The Obama Administration not only supported existing rules designed to protect local media diversity, it also strengthened them. The former administration believed that allowing local stations to consolidate was stripping some cities of competing local newscasts, reducing diversity of voices on local stations, and shifting local broadcasting further away from its public service obligations.

Public policy groups have criticized deregulation efforts for decades, particularly the 1996 Telecom Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton. That legislation lifted ownership limits on radio stations, triggering a sweeping consolidation tsunami that allowed companies like iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel Communications) to build an empire of more than 1,200 stations nationwide (as many as eight stations in a single market) after a $30 billion spending blitz.

As a result of its heavy indebtedness, the company has struggled to pay back its $20 billion outstanding debt and has committed to multiple rounds of slashing expenses at its stations, resulting in dramatic cuts in local service and staff, and turning many of its stations into automated music jukeboxes with no local announcers or staff. Listener ratings declined as a result and on April 20, the company warned investors that it may not survive the next 10 months without bankruptcy reorganization protection. These groups worry consolidation will have a similar effect on free over-the-air TV’s sense of localism.

Ironically, Sinclair Broadcasting, now attempting to acquire the station portfolio owned by Tribune Media, will not be able to participate in the next wave of consolidation because it arguably has already broken another long-standing FCC rule prohibiting one company from owning over-the-air TV stations that reach more than 39% of the U.S. audience. That rule would not be changed as a consequence of the current deregulation proposals, but it would surprise no one to see Mr. Pai and Mr. O’Rielly attempt to repeal or modify it next year.

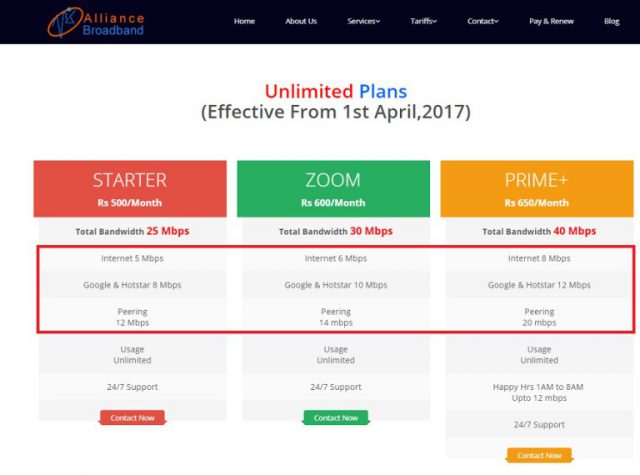

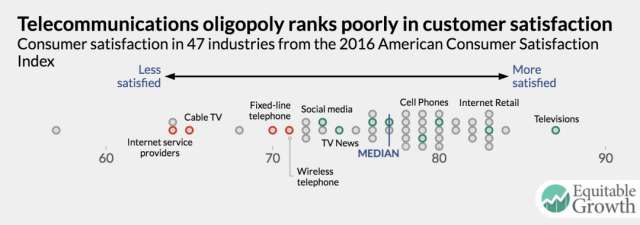

Pai and O’Rielly have been extremely critical of ownership restrictions in general. Pai has thus far advocated loosening local-TV limits, but O’Rielly has gone further calling for their complete repeal, arguing it “defies belief” that over-the-air stations have limits while they compete with “literally hundreds of competitive pay TV channels and essentially unlimited competitive internet content”

The Obama Administration argued the difference between over the air broadcasting and pay TV networks was primarily in their public service obligations. As a license holder, TV stations are required to provide service in the public interest in return for being granted a license to use the publicly owned airwaves. Since pay television networks do not use public property, they are not required to meet those obligations. Local stations, particularly those with local newsrooms, also have a long tradition of being critically important in times of public emergencies. Without an in-house staff, stations airing little or no local programming would be unlikely to continue that tradition.

Large TV owner conglomerates are already arranging financing for the impending station roundup. John Janedis, an analyst with Jeffries, told Bloomberg all of the larger TV station owners are eager for the relaxation of ownership rules so they can purchase their peers.

“The reality is everyone is talking to everybody,” Janedis said. “There are a lot of buyers out there.”

Subscribe

Subscribe