Phillip “Reality Check” Dampier

The city of Los Angeles believes if they ask for it, they will get it – gigabit fiber broadband, that is. It is too bad we have to run a reality check.

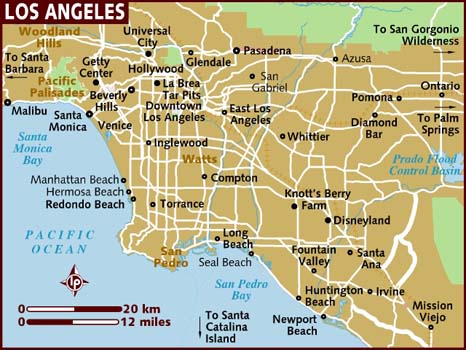

In December, the city plans to issue an ambitious Request for Proposals (RFP) inviting at least one private company to run fiber service to all 3.5 million residents (and businesses and public buildings) within the city limits. The idea, which won unanimous support from the City Council, does not exactly come with many risks for the city. The Council acknowledges the project is likely to cost up to $5 billion (we suspect more), and the city has made it clear it won’t be contributing a penny.

“The city is going into it and writing the agreement, basically saying, ‘we have no additional funding for this effort.’ We’re requiring the vendors that respond to pay for the city resources needed to expedite any permitting and inspection associated with laying their fiber,” Los Angeles IT Agency general manager Steve Reneker told Ars Technica. “If they’re not willing to do that, our City Council may consider a general fund transfer to reimburse those departments, but we’re going in with the assumption that the vendor is going to absorb those up-front costs to make sure they can do their buildout in a timely fashion.”

That is wishful thinking.

The winning vendor is not just on the hook for the cost of building the network. It also has to comply with a city requirement to give away basic 2-5Mbps broadband service, possibly recouping the lost revenue with advertising. Customers wanting faster access will pay for it. Although not required to offer phone or television service, Reneker anticipates the winning vendor will offer both to earn more revenue to pay off construction costs.

Greater Los Angeles is now served by a mix of AT&T, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, Cox, and Charter. Only Verizon has a history of providing a significant fiber optic broadband service, but it has suspended further expansion of its network. AT&T is the dominant landline provider, but considers its U-verse fiber-to-the-neighborhood design adequate for southern California. It seems unlikely any incumbent provider is likely to seriously contemplate such an expensive fiber project, especially because the city requires the winner to build an open access network that competitors can also use. Cable operators have also stated repeatedly that their existing infrastructure is more than adequate. The question providers are likely to ask is, “why do we need to partner with the City Council to build a fiber network we could build ourselves, on our own terms, that we ultimately own and control?”

The city can offer some incentives to attract an outsider, such as promising a lucrative contract to manage the city government’s telecom needs. It can also ease bureaucratic red tape that often stalls big city infrastructure projects. But Los Angeles is not exactly prime territory for a fiber build. Its notorious sprawling boundaries encompass 469 square miles, with many residents and businesses in free-standing buildings, not cheaper to serve multi-dwelling units.

The city can offer some incentives to attract an outsider, such as promising a lucrative contract to manage the city government’s telecom needs. It can also ease bureaucratic red tape that often stalls big city infrastructure projects. But Los Angeles is not exactly prime territory for a fiber build. Its notorious sprawling boundaries encompass 469 square miles, with many residents and businesses in free-standing buildings, not cheaper to serve multi-dwelling units.

Google avoided California for its fiber project reportedly because of environmental law and bureaucracy concerns. Even Google cherry-picks neighborhoods where it will deploy its fiber project in Austin, Provo, and Kansas City. The Los Angeles RFP will likely require universal coverage for the fiber network, although it will probably allow a lengthy amount of time for construction.

The City Council’s RFP comes close to promising Gigabit Fiber-to-the-Press Release.

Private providers govern their expansion efforts by an increasingly stiff formula to recover construction costs by measuring potential Return On Investment (ROI), which basically means when a company can expect to earn back the amount initially invested. Spending $5 billion on a fiber network that could actually cut expected Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) with a free broadband offer is going to raise eyebrows. Convincing investors to chip in on a fiber network “open to competitors” will also elicit a lot of frowning faces.

Wall Street analysts rolled their eyes when Verizon rolled out FiOS. It was “too expensive” and provided too few avenues for a quick ROI. ‘Verizon built a Lamborghini Aventador fiber network when a Honda Accord would have done just fine in the absence of fierce competition,’ analysts complained. Why spend all this money on fiber when fat profits were waiting to be harvested from high-ARPU wireless service? Verizon got the message and ceased expansion. AT&T never walked that Wall Street plank in the first place, delivering a less capable Chevrolet Spark network known as U-verse.

The city is likely to be disappointed with the proposals they receive, in much the same way local governments begging for competition from other cable companies get no positive results. The economics and expectations of today’s private broadband market makes it extremely unlikely an incumbent provider is going to rock a boat that has delivered comfortable broadband profits with a minimum of investment.

Breaking the broadband duopoly of high prices for slow service is only likely in the private sector if deep-pocketed revolutionaries like Google can self-finance game-changing projects. Los Angeles will likely have to sweeten its invitation to attract interest from players serious enough to spend $5 billion. It will likely have to invest some money of its own in a public-private partnership. Perhaps an even better idea is to take control of the city’s broadband destiny more directly with a community project administered by a qualified broadband authority with proven experience in the telecom business.

There is no reason private companies cannot be active participants in whatever project is ultimately built, but these companies are not charities and if their financial backers don’t see a pathway to profit running fiber rings around LA today, an RFP to build a fiber network with city strings-attached isn’t likely to garner serious interest tomorrow.

Subscribe

Subscribe