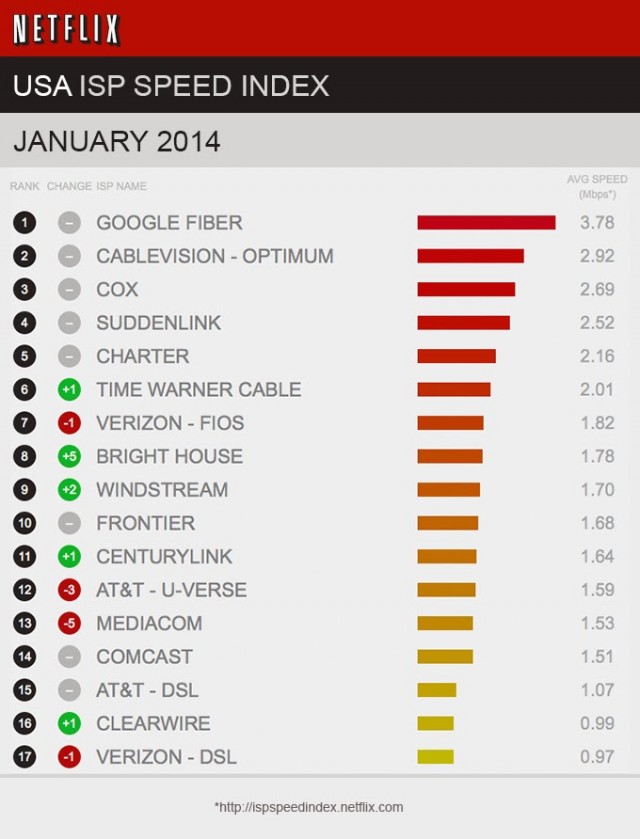

The largest drops in Netflix streaming speeds are coming from ISPs that may be stalling necessary upgrades at the cost of their paying customers’ online experience.

Netflix performance for Verizon customers is deteriorating because Verizon may be delaying bandwidth upgrades until it receives compensation for handling the growing amount of traffic coming from the online video provider.

Verizon customers have increasingly complained about Netflix slowdowns during prime-time, especially in the northeast, and Netflix’s latest statistics confirm FiOS customers have seen average performance drop by as much as 14% in the last month alone.

Verizon told Stop the Cap! a few weeks ago the company was not interfering with Netflix traffic or degrading its performance, but there is growing evidence that may not be the whole story. The Wall Street Journal reports Netflix and at least one bandwidth provider suspect phone and cable companies are purposely stalling on upgrading connections to handle traffic growth from Netflix until they are compensated for carrying its video traffic.

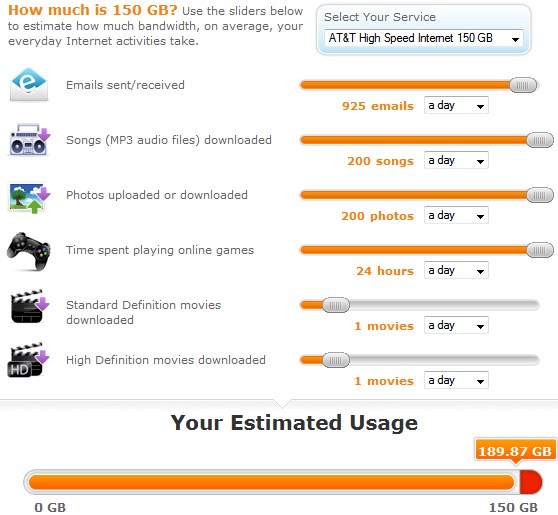

The dispute involves the plumbing behind parts of the Internet that are invisible to consumers. As more people stream movies and television, that infrastructure is getting strained, intensifying the debate over who should pay for upgrades needed to satisfy America’s online-video habit.

Netflix wants broadband companies to hook up to its new video-distribution network without paying them fees for carrying its traffic. But the biggest U.S. providers—Verizon, Comcast, Time Warner Cable and AT&T Inc. —have resisted, insisting on compensation.

The bottleneck has made Netflix unwatchable for Jen Zellinger, an information-technology manager from Carney, Md., who signed up for the service last month. She couldn’t play an episode of “Breaking Bad” without it stopping, she said, even after her family upgraded their FiOS Internet service to a faster, more expensive package. “We tried a couple other shows, and it didn’t seem to make any difference,” she said. Mrs. Zellinger said she plans to drop her Netflix service soon if the picture doesn’t improve, though she will likely hold on to her upgraded FiOS subscription.

She and her husband thought about watching “House of Cards,” but she said they probably will skip it. “We’d be interested in getting to that if we could actually pull up the show,” she said.

Netflix relies on third-party traffic distributors to deliver much of its streamed programming to customers around the country. Cogent Communications Group is a Netflix favorite. Cogent maintains two-way connections with many Internet Service Providers. When incoming and outgoing traffic are generally balanced, providers don’t complain. But when Cogent started delivering far more traffic to Verizon customers than what it receives from them, Verizon sought compensation for the disparity.

“When one party’s getting all the benefit and the other’s carrying all the cost, issues will arise,” Craig Silliman, Verizon’s head of public policy and government affairs told the newspaper. The imbalance is primarily coming from the growth of online video, and as higher definition video grows more popular, traffic imbalances can grow dramatically worse.

A spat last summer between Cogent and some ISPs is nearly identical to the current slowdown. Ars Technica reported the traditional warning signs providers used to start upgrades are increasingly being ignored:

“Typically what happened is when the connections reached about 50 percent utilization, the two parties agreed to upgrade them and they would be upgraded in a timely manner,” Cogent CEO Dave Schaeffer told Ars. “Over the past year or so, as we have continued to pick up Netflix traffic, Verizon has continuously slowed down the rate of upgrading those connections, allowing the interconnections to become totally saturated and therefore degrading the quality of throughput.”

Schaeffer said this is true of all the big players to varying degrees, naming Comcast, Time Warner, CenturyLink, and AT&T. Out of those, he said that “AT&T is the best behaved of the bunch.”

Letting ports fill up can be a negotiating tactic. Verizon and Cogent each have to spend about $10,000 for equipment when a port is added, Schaeffer said—pocket change for companies of this size. But instead of the companies sharing equal costs, Verizon wants Cogent to pay because more traffic is flowing from Cogent to Verizon than vice versa.

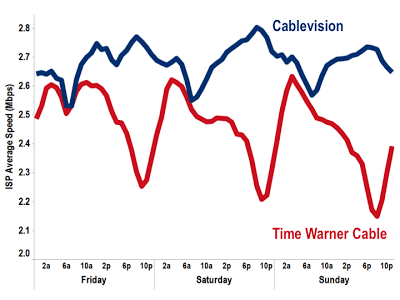

Cablevision, which participates in Netflix’s Open Connect program, experiences no significant speed degradation during prime time. The same cannot be said of Time Warner Cable, which refuses to take part.

Netflix offered a solution to help Internet Service Providers manage its video traffic. Netflix’s Open Connect offers free peering at common Internet exchanges as well as free storage appliances that ISPs can connect directly to their network to distribute video to customers. Free is always good, and Netflix claims many ISPs around the world have already taken them up on the offer, slashing their transit costs along the way.

A few major North American ISPs have also agreed to take part in Open Connect, including Frontier Communications, Clearwire, Telus, Bell, Cablevision and Google Fiber. Open Connect participating ISPs also got an initial bonus for participating they could offer customers – exclusive access to SuperHD streaming.

But most Americans would not get super high-resolution streaming because the largest ISP’s refused to participate, seeking direct compensation from content providers to carry traffic across their digital pipes instead.

On Sep. 26, 2013 Netflix decided to offer SuperHD streaming to all customers, regardless of their ISP. As a result, one major ISP told the newspaper Netflix traffic from Cogent at least quadrupled. ISPs taking Netflix up on Open Connect saw almost no degradation from the increased traffic, but not so for Verizon, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, and Comcast customers.

Net Neutrality advocates fear the country’s largest phone and cable companies are making an end-run around the concept of an Open Internet. Providers can honestly guarantee not to interfere with certain web traffic, but also refuse to keep up with needed upgrades to accommodate it unless they receive payment. The slowdowns and unsatisfactory performance are the same in the end for those caught in the middle – paying customers.

“Customers are already paying for it,” said industry observer Benoît Felten. “You sell a service to the end-user which is you can access the Internet. You make a huge margin on that. Why should they get extra revenue for something that’s already being paid for?”

Some of the web’s biggest players including Microsoft, Google and Facebook may have already capitulated — agreeing to pay major providers for direct connections that guarantee a smoother browsing experience. Netflix has, thus far, held out against paying ISPs to properly manage the video content their subscribers want to watch but in some cases no longer can.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Gizmodo

Gizmodo

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications.

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications. According to Bloomberg News, the

According to Bloomberg News, the

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

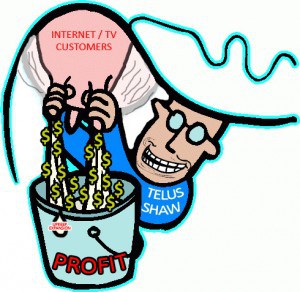

Bigger discounts can be had for television and Internet service — cable television remains immensely profitable in Canada and broadband is cheap to offer, especially in cities. Americans often pay $80 or more for digital cable television packages, Canadians pay an average of $60.

Bigger discounts can be had for television and Internet service — cable television remains immensely profitable in Canada and broadband is cheap to offer, especially in cities. Americans often pay $80 or more for digital cable television packages, Canadians pay an average of $60.