Andre Vrignaud of Seattle has been benched for a year by Comcast for using too much of its Internet service.

From time to time, we get reports from Comcast customers victimized by the company’s 250GB usage cap. The nation’s largest cable broadband provider implemented that arbitrary limit back in 2008 after the Federal Communications Commission told the company they could not throttle the speeds of customers using applications like peer-to-peer file sharing software — then pegged as the usual suspect for turning “ordinary” broadband users into “data hogs.”

For at least 18 months, Comcast’s usage cap came with no measurement tools or real explanation most customers could find about what a “gigabyte” was, much less how many of them they “used” that month. Only last year, Comcast finally rolled out usage measurement tools for customers who bother to find them on their website. New customers signing up for service never even realize there is a usage cap until a thick brochure of legalize comes with the installer outlining the company’s Acceptable Use Policy.

Still, compared to some of the usage cap battles Stop the Cap! was fighting three years ago, Comcast was the least of our problems. Frontier’s infamous 5GB usage allowance was the worst we’d ever seen, Cable One’s IRS-like usage policies required an academic to explain them, and Time Warner Cable’s ‘lil experiment in broadband rationing with a 40GB usage cap experiment crashed and burned soon after being announced in the lucky test cities scheduled to endure it. That doesn’t make Comcast’s cap fair or right, but protecting consumers from these schemes requires triage.

But we remember well Comcast’s promise that it would regularly revisit and adjust its usage cap to reflect the dynamic usage of its customers. That’s just one more broken promise from a broadband provider with an Internet Overcharging scheme. In fact, Comcast has not moved its cap one inch since the day it was announced, although they have increased their rates. The only thing going for the cable giant is that it doesn’t treat “250GB” as a guillotine. In fact, the cable company only sends the usage police after the top few percent of users that exceed it, issuing a warning not to exceed the cap again during the next six months, or face a year without having the service.

This punitive policy is what Time Warner Cable CEO Glenn Britt loves to rail against. For him, broadband usage should never be penalized — it should be exploited for all the money the provider can possibly get from customers. That’s why Britt favors a consumption billing system that starts off with a high monthly price for everyone, than goes much higher the more you use. Would the neighborhood crack dealer cut you off for using too much? Of course not. Feeding your broadband usage habits can mean fat profits, and investors love it.

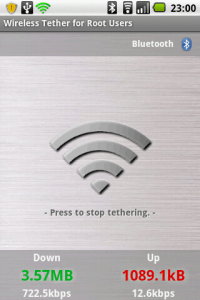

Andre Vrignaud, a 39-year-old gaming consultant in Seattle, wrote us (and many others) about his own experience with Comcast’s usage ban. He’s a victim of it, having been warned once about usage and then ultimately told his cable modem was disabled for a year. For Vrignaud, it was a case of using a cloud storage file backup provider, moving very high resolution images around, and having roommates. Since Comcast counts upload and download traffic towards its usage limit, it’s not hard to see what can happen to anyone trying to back up today’s supersized hard drives. What’s especially ironic is that Comcast itself sells online file backup services — which also counts towards your cap.

Comcast’s attitude about its decision to ban Vrignaud from its broadband service for a year was simple enough: it’s a clear cut case of violating their usage caps. In their view, heavy users slow down broadband service for everyone else in the neighborhood. So they set a policy that cuts them off when they use too much.

Comcast’s attitude about its decision to ban Vrignaud from its broadband service for a year was simple enough: it’s a clear cut case of violating their usage caps. In their view, heavy users slow down broadband service for everyone else in the neighborhood. So they set a policy that cuts them off when they use too much.

To add insult to injury, broadband-disabled Comcast customers have to call Comcast’s Retentions & Cancellations Department to get the billing stopped on his disabled service. Vrignaud had to negotiate with a representative whose instinct is to keep you a Comcast customer at all costs, even when the company won’t allow you to be one!

But is Comcast really facing a congestion issue? Not if you happen to be a business customer at the same address, using the exact same infrastructure that residential customers in the neighborhood use. Business Class service has no usage limits at all — “congested neighborhood” or not. And that is where Comcast’s argument simply starts to fall apart.

We’ve been in touch with Vrignaud privately in an effort to help him find a way back to his broadband service. The alternative is DSL from Qwest/CenturyLink, and unless you live in an area where the phone company has upgraded their networks to support ADSL 2+ or other advanced flavors of DSL, that represents quite a speed downgrade.

Our readers have told us Comcast representatives have several unofficial ways of dealing with heavy users who have gotten their first warning from the company. Some have told customers to sign up for a second residential account under the name of someone else in the home to allot themselves an additional 250GB of usage. Others recommend signing up for a business account, which means no usage cap at all. For those who have been cut off, signing up as a new customer under the name of someone else in the household usually gets you back in the door, albeit facing the same usage cap issue all over again.

The problem Vrignaud encountered is Comcast’s clumsy way of dealing with customers, like himself, who have been sentenced to a year without broadband service (from them).

Vrignaud explored the route we recommended — Business Class service — and found he couldn’t sign up. Evidently Comcast’s ban is tied to his personal Social Security number, and when he tried to enroll in Business Class service using it, he was stopped dead in his tracks.

Turns out that once Comcast has cut your broadband account for violating their data cap policy you are verboten from being a Comcast customer for 1 year. That’s right:

After being cut off from Comcast’s consumer internet plan due to using too much data, I’m told I’m ineligible to use Comcast’s recommended solution, their business internet plan that allows the unlimited use of data — solely because I made the mistake of actually using “too much” data in the first place.

As the sales rep said in my Google Voicemail message, “what’s interesting is that if you would have started off on the business side of the house, since we don’t have a cap limitations [sic] you would’ve been fine.”

Vrignaud also mentioned he was unsure if Comcast required a business Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN) in order to sign up for Business Class service. In fact, for our readers who have gone this route, it turned out not to be necessary. They just put their Social Security number in the space reserved for a TIN and had no problems. Vrignaud would have a problem, however, because his Social Security number is effectively “poisoned” for the year. He would need to obtain a specific kind of TIN — an Employer Identification Number (EIN) to proceed. Luckily, it takes less than five minutes to apply for one online and is free. The number displayed at the end of the process would be the one to use with Comcast. An alternative suggestion would be to sign up for service under the name of someone else in the household.

For those on Comcast’s bad side, there is more hoop-jumping to get your service back than at the Ringling Bros. circus.

Should all this even be necessary?

Broadband service carries up to a 90% profit margin.

Stop the Cap! thinks not. While Comcast may have endured last-mile congestion on its shared cable broadband network in days past, the company’s aggressive upgrades to DOCSIS 3 technology makes congestion-based usage limits more of an excuse than a reality. Comcast is pitching faster broadband speeds than ever, all hampered by the same 250GB usage limit. While residential and business class customers share the same physical cable lines strung across neighborhoods, one faces a usage cap and the other does not. It’s simply not credible. Comcast’s punitive usage cap scheme throws away their own customers and the revenue they bring.

Vrignaud wants the option of getting his service back, perhaps by buying additional usage. That’s Time Warner Cable’s dream-come-true, and one we are concerned about. Once broadband usage is limited and monetized, it becomes a commodity that can be priced to earn enormous additional revenue for cable operators, regardless of the actual cost of providing the service. That’s a dangerous precedent in today’s duopolistic broadband marketplace, because the cost per gigabyte will likely be on the order of a thousand times or more the actual cost, with no competitive pressure to keep that cost down. That’s how Canada ended up in its Internet Overcharging pickle, where providers call $1.50-$5 per gigabyte “reasonable,” even though it costs them only pennies (and dropping) to deliver. Some providers are even raising those prices, even as their costs plummet. That’s not a road we want the cable or telephone industry walking down, or else we’ll find today’s enormous cable TV bills pale in comparison to the outrageous broadband service bills of the future. Time Warner Cable provided a helpful preview in 2009 when they proposed unlimited 15/1Mbps residential service at the low, low price of $150 a month.

Vrignaud is just one more example of why Internet Overcharging risks America’s broadband future. It’s an end run around Net Neutrality, its arbitrary, and unjustified. The rest of the world is racing to discard what they called congestion pricing almost as fast as America’s providers (and their Wall Street cheerleaders) are racing towards Internet Overcharging. The United States should be following Canada’s lead and hold providers to account for this kind of Internet pricing and force them to prove its warranted, or be rid of it. With virtually every provider earning enormous profits off Internet service at today’s speed-based pricing, there remains no justification to overcharge customers for their broadband usage.

Stop the Cap! reader Larry Posk from Atlanta just threw AT&T overboard, fed up with the company’s anti-consumer policies, and Sprint paid him $125 to walk.

Stop the Cap! reader Larry Posk from Atlanta just threw AT&T overboard, fed up with the company’s anti-consumer policies, and Sprint paid him $125 to walk.

Subscribe

Subscribe