A controversial proposal by Montana’s largest cable operator to use public funding for construction of a fiber optic network linking the state’s seven Indian reservations has been rejected by federal officials.

A controversial proposal by Montana’s largest cable operator to use public funding for construction of a fiber optic network linking the state’s seven Indian reservations has been rejected by federal officials.

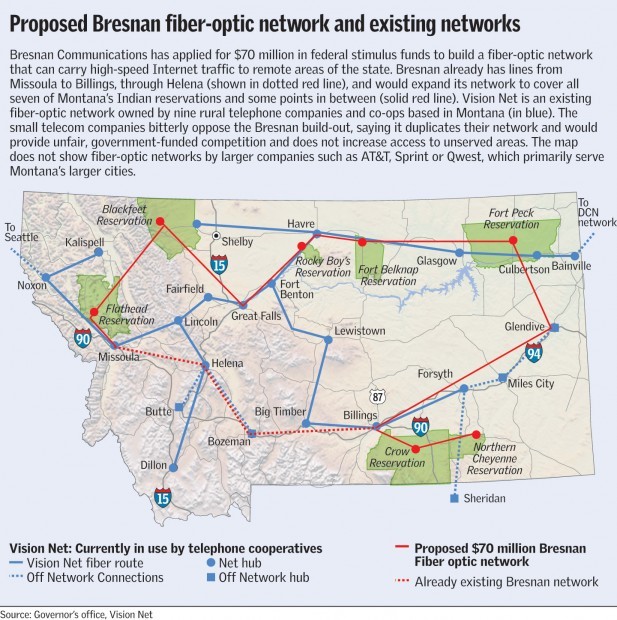

Bresnan Communications sought $70 million broadband stimulus grant to construct the 1,885-mile fiber-optic network to improve broadband connectivity. Independent and cooperative telephone providers objected, claiming the proposal would duplicate services they already provide.

The debate over broadband stimulus funding in rural Montana has been contentious, particularly after incumbent telephone providers accused Bresnan of lying on their application — implying funds would directly improve broadband service to Native American communities. They accused the cable operator of using public funds to enhance their own “middle mile network,” infrastructure that helps Bresnan distribute broadband traffic between its central offices and data centers, but not “the last mile” connection customers actually rely on to obtain service.

Montana is not alone in the debate over how federal broadband stimulus money should be spent. With a limited pool of funds, and an overwhelmed National Telecommunications and Information Agency tasked with processing an unexpected flood of applications, funding decisions have become increasingly political, and many incumbent providers have learned they can jam up an applicant just by flooding federal agencies with comments opposing projects that impact on their service areas.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/KULR Billings Montana Broadband Workshop and Broadband Speed 1-19-2009 and 8-30-2009.flv[/flv]

KULR-TV in Billings covered the NTIA Grant Broadband Workshop held last January and also covered Montana’s woeful existing broadband speeds in these two reports. (1/19/2009 & 8/30/2009 – 2 minutes)

Because “last mile” projects are the most threatening to incumbent providers, these applications typically get the most opposition. The NTIA, in an effort to reduce their workload, has in turn started focusing on “middle mile” projects which often benefit incumbents, pushing public tax dollars into pre-existing private networks. That looks great on provider balance sheets — that’s money they don’t have to raise from stockholders or other investors. Diverting those funds away, even from currently unserved areas, also protects providers’ flanks from the potential threat of competition, both now and in the future.

In Montana, chasing few potential customers spread out over vast distances in rural areas makes the potential threat from competition even scarier. There, many small phone companies exist as co-ops, less concerned with raking in profits. They fear the potential threat Bresnan Communications could bring to their viability if the cable operator gets a stronger foothold in their territories, especially when using tax dollars to do so. But is the threat that large for well-run, customer-oriented companies and co-ops?

Many rural areas served by co-ops and other small independent companies actually receive better and faster broadband service than their more urban counterparts, argues Bonnie Lorang, general manager of Montana Independent Telecommunications Systems, an independent phone company trade group. That’s because the state’s large urban phone company – Qwest, does not provide DSL into more distant suburban and rural service areas, and has only reached 75 percent of its customers with broadband service. Smaller independent providers, particularly member-owned cooperatives, are accustomed to serving residents Qwest has been slow to reach.

While true for those forced to rely on Qwest DSL service, those with access to cable modem service can do better. Bresnan provides up to 8Mbps service for residents in its mountain west region covering parts of Wyoming, Montana, and the western slope of Colorado. Expanding Bresnan’s service where economically feasible remains a priority for the company, and broadband stimulus funding may make the difference between an “unprofitable” area and one that can be profitable if certain infrastructure costs are underwritten.

“Bresnan has a history of investing in communities that are not considered larger communities,” according to said Shawn Beqaj, spokesman for Bresnan. “Our philosophy is that smaller communities deserve every bit of the services that large communities have.”

Bresnan’s grant application received support from Montana governor Brian Schweitzer, the state’s Native American population, and some consumers unhappy with their current broadband choices, if any.

Montana's phone companies are running these print ads objecting to the broadband stimulus proposal from Bresnan Communications (click to enlarge and see the full ad)

On the other side, the phone companies and their trade groups: the Montana Telecommunications Association and Montana Independent Telecommunications Systems, and the state’s utility oversight agency. They protested Bresnan was unnecessarily duplicating existing service, and potentially getting taxpayer money to do so. They also hinted Bresnan exploited Native Americans in an application tailor-written to appeal to federal officials seeking improved service for disadvantaged and challenged minority groups. Besides, the phone companies argued, Bresnan broke the rules from the outset by only agreeing to provide $6 million in company-provided matching funds, less than the 20 percent in matching dollars required by the stimulus program.

“If an area is unserved, prove it and spend the money on that,” Geoff Feiss, a representative of the Montana Telecommunications Association (MTA), told the Billings Gazette. “But don’t spend $70 million on an overbuild network that’s going to deprive investment from existing networks and leave behind collateral damage that we’ll never recover from.”

Montana’s Public Service Commission ended up on the side of the MTA, calling Bresnan’s proposal “seriously flawed.”

Bresnan and their allies shot back that phone companies complaining about federal dollars being spent on broadband projects was hypocritical, considering many of those companies receive government assistance from the Universal Service Fund to stay in business themselves.

Consumers looking for broadband were left in the middle or left out entirely. Many residents of the state are forced to rely on dial-up, satellite, or have been left indefinitely on waiting lists for future DSL expansion projects that take forever to materialize. Choice is an option too many residents don’t have. The Great Falls Tribune shared a story familiar to many Montanans:

Tim Lanham can’t get Qwest DSL at his eastside Great Falls home. It’s available to his neighbors across the street and at his office a block away.

He’s called Qwest about the situation, but typically can’t get through to a real person. The whole thing is frustrating, he said.

Lanham used to use Sofast. After its service went down, he switched to a Verizon Wireless card, but that can only be used on one computer at time. Now he has broadband Internet through Bresnan. Still, he wishes he had more options.

“I’d like the different options,” Lanham said. “Essentially they leave us with very few choices.”

At the heart of the debate is how to address the “digital divide” between those with Internet access and those without, and improving connectivity for those stuck with outdated, expensive, and slow “broadband.”

The state’s utility commission believes Montana’s primary problem exists in “the last mile,” namely getting broadband service to rural residents who currently are forced to use dial-up or satellite fraudband service that offers slow speed, tiny usage allowances, and a high price tag. In most cases, telephone companies have deemed these rural residents too few in number and too far apart to make investments in DSL service worthwhile. Using broadband stimulus money to subsidize the costs of providing service to rural America provides a direct path to broadband for those who may not obtain access any other way short of moving.

Larger providers have been urging that less money be spent on “last mile” projects and that funding be redirected into “middle mile” projects, which could dramatically reduce the costs companies have to pay to maintain and upgrade their own backbone infrastructure. Examples of these kinds of projects include installing fiber optic cables between telephone company central offices or extended service “remotes” which reduce the distances between customers and telephone company facilities, extending the distance DSL can cover in rural areas.

Larger providers have been urging that less money be spent on “last mile” projects and that funding be redirected into “middle mile” projects, which could dramatically reduce the costs companies have to pay to maintain and upgrade their own backbone infrastructure. Examples of these kinds of projects include installing fiber optic cables between telephone company central offices or extended service “remotes” which reduce the distances between customers and telephone company facilities, extending the distance DSL can cover in rural areas.

For now, Montana will have to wait for both.

Bresnan officials will meet with tribal and state commerce officials before deciding what to do next.

Walter White Tail Feather, director of economic development for the Assiniboine and Sioux tribes on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana, told the Gazette he hopes Bresnan reapplies for the funding.

“We think we can make a better proposal this second round,” he said. “This first one was a learning experience. … What we really are doing is working with the state to empower ourselves as a tribal government to create a business, to create opportunities that we don’t have.”

The state’s small phone companies may have won the battle, but are now concerned they could ultimately lose the war over obtaining broadband stimulus money themselves, at least from the NTIA.

Jay Preston, chief executive officer of Ronan Telephone Co., told the Gazette two federal agencies now will be deciding who gets broadband stimulus money: The National Telecommunications and Information Administration and the Rural Utilities Service.

The NTIA “seems to be really, really focusing on the middle-mile idea,” Preston said, while RUS probably will approve funds for rural telephone companies that already are the federal agency’s customers. The RUS loans money to rural co-ops for a variety of projects.

Regardless of where the money comes from, frustrated Montana residents just want better service. The state ranks dead last, tied with Alaska, in broadband speed, according to a study from the Communications Workers of America. Residents enjoy an average broadband speed of just 2.3Mbps.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/KFBB Great Falls Montana ISP Flounders 11-10 – 11-13-2009.flv[/flv]

Already-broadband-challenged Montana residents faced a major headache when one of the state’s large Internet Service Providers, SoFast, suddenly shut down last November. KFBB-TV in Great Falls followed the story over three days in these three reports from November 10-13th, 2009. (5 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe