United States Circuit Judge Thomas L. Ambro has sat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit hearing countless legal challenges of federal government rules, regulations, and laws since 2000. In fact, he has heard so many cases it might have worried petitioners when he opened his majority-held ruling with the words “Here we are again.”

United States Circuit Judge Thomas L. Ambro has sat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit hearing countless legal challenges of federal government rules, regulations, and laws since 2000. In fact, he has heard so many cases it might have worried petitioners when he opened his majority-held ruling with the words “Here we are again.”

Ambro (from the court’s decision):

“Here we are again. After our last encounter with the periodic review by the Federal Communications Commission (the “FCC” or the “Commission”) of its broadcast ownership rules and diversity initiatives, the Commission has taken a series of actions that, cumulatively, have substantially changed its approach to regulation of broadcast media ownership. First, it issued an order that retained almost all of its existing rules in their current form, effectively abandoning its long-running efforts to change those rules going back to the first round of this litigation. Then it changed course, granting petitions for rehearing and repealing or otherwise scaling back most of those same rules. It also created a new “incubator” program designed to help new entrants into the broadcast industry. The Commission, in short, has been busy. Its actions unsurprisingly aroused opposition from many of the same groups that have battled it over the past fifteen years, and that opposition has brought the parties back to us.”

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai is presiding over a sweeping deregulatory agenda that critics fear will further consolidate an already corporate dominated media landscape that has given a handful of companies approval to own and operate hundreds of radio and television stations, many in the same profitable media markets. One corporate owner can already own several local radio and TV stations and the FCC is working to further ease already relaxed ownership limits that could allow companies like Sinclair, Nexstar, and iHeartMedia to buy even more radio and TV stations.

The History of Broadcast Deregulation (1996-2019)

Judge Ambro

Deregulators targeting media ownership limits have been on a tear since the mid-1990s, with the first major changes in decades ushered in by the Clinton Administration’s 1996 Telecommunications Act, which required the FCC to conduct a review of media ownership rules every two years. The 1996 law required the FCC to determine “whether any of such rules are necessary in the public interest as the result of competition.” If not, the Commission is required by law to “repeal or modify any regulation it determines to be no longer in the public interest.”

What is in the “public interest” has historically been in the eye of the beholder. Democrats on the FCC have been wary of media consolidation and take a skeptical view of arguments that consolidation enhances competition and improves the efficiency of radio and television stations that can share resources. Democrats worry about the loss of diversity, cost-cutting, and consolidated control over news gathering operations. Republicans have been traditionally friendly to the argument that consolidation has allowed marginal stations to sell operations to a better funded corporate owner, with healthier broadcast competition the result. Republicans also argue regulation is unnecessary in a diverse media market where consumers have a choice of traditional broadcasters, satellite radio, cable television, internet streaming, etc. That makes strict ownership limits no longer necessary.

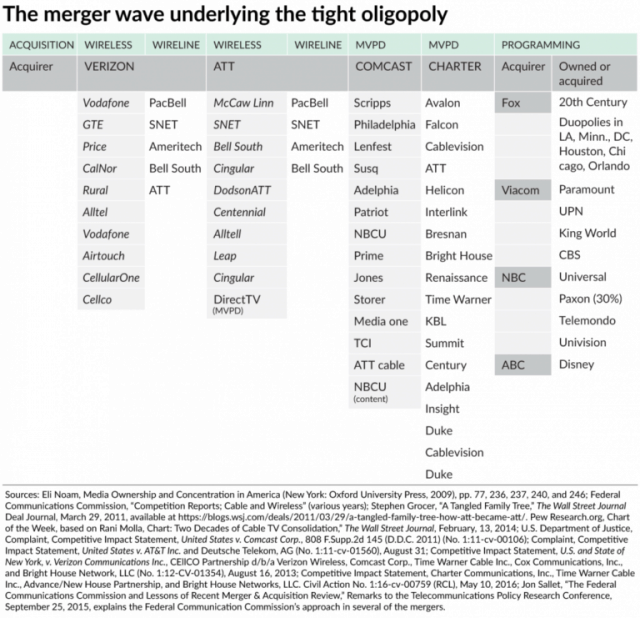

Neither side can argue with the fact that as a result of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, over 4,000 local radio stations were purchased from independent and small corporate owners and merged under the umbrella of a handful of giant corporate media companies. Although proponents of the 1996 Act claimed it would increase competition, in fact it did the exact opposite. With many stations now under the ownership of a handful of companies, corporate owners frequently programmed each station with a different format specifically to avoid head-to-head competition. While some listeners felt this increased the diversity of music formats heard on the air, many also noticed local voices began disappearing from those stations, replaced with automation or voices that originated in other cities. Some corporate owners cut costs by hiring a small team of announcers to program dozens of radio stations around the country. Local news coverage was also often among the first things to be cut.

Another consequence of the 1996 Act was a steep decline in minority ownership of stations. In particular, minority ownership of TV stations dropped to an all-time low since the federal government began tracking such data in 1990.

The consolidation wave did some corporate owners no favors either. Clear Channel Communications (now iHeartMedia), became a ripe target for a leveraged buyout after successfully acquiring hundreds of local stations. In 2008, Bain Capital and Thomas H. Lee Partners launched a successful takeover of Clear Channel for $24 billion, largely financed with debt that Bain and THL Partners put on Clear Channel’s books. Over 2,440 employee layoffs and cost cutting quickly followed, while the new owners leveraged the stations it now owned to maintain adequate financing to cover interest payments on its enormous debts. As The Great Recession took hold, advertising revenue diminished and credit markets became stingy and unforgiving. By 2010, the company faced bankruptcy and debt holders were growing impatient. Over the next several years, several debt restructuring efforts were undertaken to help the company pay down its debts, but debt holders finally had enough in 2018, forcing what is now known as iHeartMedia into bankruptcy reorganization.

The FCC itself later admitted that the consolidation frenzy caused negative effects that should be addressed. But the incoming George W. Bush Administration initially had other ideas and under the leadership of FCC Chairman Michael Powell, the majority of Republicans on the Commission supported further relaxation of ownership rules. In early 2003, the FCC held a single public hearing on the matter, which sparked outrage among many Americans concerned about the impact media consolidation had already had on their local stations. By June of that year, nearly two million letters from the public opposing further media consolidation had arrived at the FCC. The Commission, despite the public outcry, ultimately voted 3-2 to repeal a long-standing ban prohibiting a local newspaper from also owning a local television station (or vice versa) and also relaxed other ownership rules, claiming they were no longer necessary to protect competition, localism, or ownership diversity.

The FCC itself later admitted that the consolidation frenzy caused negative effects that should be addressed. But the incoming George W. Bush Administration initially had other ideas and under the leadership of FCC Chairman Michael Powell, the majority of Republicans on the Commission supported further relaxation of ownership rules. In early 2003, the FCC held a single public hearing on the matter, which sparked outrage among many Americans concerned about the impact media consolidation had already had on their local stations. By June of that year, nearly two million letters from the public opposing further media consolidation had arrived at the FCC. The Commission, despite the public outcry, ultimately voted 3-2 to repeal a long-standing ban prohibiting a local newspaper from also owning a local television station (or vice versa) and also relaxed other ownership rules, claiming they were no longer necessary to protect competition, localism, or ownership diversity.

Among the changes:

- Any one company could now own up to 45% of local stations in a market (it was 25% in 1985, relaxed to 35% in the 1990s).

- The newspaper/TV station cross-ownership ban was eliminated.

- Alternative forms of media and their popularity would now be considered when determining whether a company owned or controlled too much of a local media market. The FCC would now also consider magazines, cable channels, and internet services to decide if one owner had become too dominant.

- License renewals no longer considered whether a station was adequately serving in the “public interest.”

Community Activists Strike Back at Corporate Consolidation and Media Homogenization

The FCC’s ability to ram through the rules changes, despite public opposition, was immediately met with a formidable 2003 court challenge by the Prometheus Radio Project, a non-profit advocacy and community organizing group that opposed corporate consolidation of radio stations and supported the low-power (LPFM) radio movement, which sought low-cost licensing of community radio stations to preserve localism and provide diverse radio programming.

The FCC’s ability to ram through the rules changes, despite public opposition, was immediately met with a formidable 2003 court challenge by the Prometheus Radio Project, a non-profit advocacy and community organizing group that opposed corporate consolidation of radio stations and supported the low-power (LPFM) radio movement, which sought low-cost licensing of community radio stations to preserve localism and provide diverse radio programming.

Prometheus Radio Project v. FCC garnered support from several independent broadcasters and community groups like the Consumer Federation of America, the National Council of Churches of Christ, and the Media Alliance. In 2004, the same U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals that heard the most recent case against the FCC’s deregulation efforts ruled 2-1 in favor of Prometheus. The decision was written by the same Judge Ambro that remarked ‘here we are again’ this week. The ruling required the FCC to re-examine its media ownership rules and found the FCC’s justifications for the changes to be inadequate and in one case relied on “irrational assumptions and inconsistencies.” The Supreme Court later affirmed the Court of Appeals’ decision, frustrating the efforts of deregulators.

Media consolidation was once again a priority item on the FCC’s agenda after the election of President Donald Trump. Republican FCC Chairman Ajit Pai once again took aim at the already-relaxed media ownership rules to relax them even further. In a Republican-dominated 3-2 decision in November, 2017, the FCC once again eliminated the newspaper/TV station cross-ownership ban and would now permit one company to own two of the four largest television stations in a market, instead of just one.

Those changes were the ones struck down this week by the Court of Appeals.

FCC and Its Allies: Since You Don’t Stand to Make Millions from Consolidation, You Should Have No Say

An exasperated Judge Ambro repeatedly took the FCC (and indirectly Ajit Pai, the current chairman) to task for ignoring the Court’s instructions on formulating media ownership policies that would survive court challenges.

An exasperated Judge Ambro repeatedly took the FCC (and indirectly Ajit Pai, the current chairman) to task for ignoring the Court’s instructions on formulating media ownership policies that would survive court challenges.

But first, Ambro’s decision eviscerated attempts by the FCC and interest groups allied with its deregulation policies to undercut public and opposition participation in the debate. First, both argued that the opposition lacked standing to sue the FCC in court over its new deregulation policy because they do not have any business interests at risk and cannot be harmed directly by the decision to deregulate. When the opposition filed legal briefs to prove standing, the FCC and its allies argued it was too late to submit proof and it should not be considered by the court.

Ambro’s decision rejected those arguments, noting “the same parties have been litigating before us for a decade and a half. It was not unreasonable […] to assume that their qualification to continue in the case was readily apparent.”

Ambro also took issue with the FCC’s argument that those in opposition to its new rules were only speculating it would lead to consolidation.

“The problem is that encouraging consolidation is a primary purpose of the new rules. This is made clear throughout the Reconsideration Order, see, e.g., 32 F.C.C.R. at 9811, 9836,” Ambro wrote. “The Government cannot adopt a policy expressly designed to have a certain effect and then, when the policy is challenged in court by those who would be harmed by that effect, respond that the policy’s consequences are entirely speculative.”

But it did not stop the FCC from trying.

The FCC also argued that opponents were worrying too much about the impact of the new rules. FCC lawyers reminded the court the agency would still carefully consider any new merger proposals put before it. Judge Ambro found that argument “immaterial.”

“The point is that, under the new rules, it will approve mergers that it would have rejected previously, with the rule changes in the Reconsideration Order the key factor causing those grants of approval,” Ambro wrote.

“We emerge from the bramble to hold that Regulatory Petitioners have standing,” Ambro concluded, signaling his irritation with attempts to stymie the lawsuit against the FCC.

Why the Top-Four Station Limit Matters

One of the groups allied with the FCC attempted to argue that the “top-four rule” that forbids any one company from owning or controlling more than one of the top-four television stations in a major local market is arbitrary, irrational, and indefensible.

But the court ruling explained why the rule exists and why it matters.

“The basic logic of the top-four rule, as we recognized in 2004, is that while consolidation may offer efficiency gains in general, mergers between the largest stations in a market pose a unique threat to competition. Although there might be other more tailored, and more complex, ways to identify those problematic mergers, the simplest is to declare, as the Commission has done, that mergers between two or more of the largest X stations in a market are not permitted. The choice of X must be somewhat arbitrary: each market’s contours will be slightly different, and no single bright-line rule can capture all this complexity. But the television industry does generally feature a distinct top-four, corresponding to the four major national networks, and four is therefore a sensible number to pick. And this is exactly the kind of line-drawing, where any line drawn may not be perfect, to which courts are the most deferential.

“[…]The Commission has the discretion to adopt a blunt instrument such as the top-four rule if it chooses. Indeed we confronted, and rejected, this exact argument—that treating all top-four stations the same wrongly ignored the variation in market structures—in Prometheus I. Id. at 417–18.

“Nor is it improper that the FCC’s justification for this rule is the same as it was in the 2002 review cycle. Section 202(h) requires only that the Commission think about whether its rules remain necessary every four years. It does not imply that the policy justifications for each regulation have a shelf-life of only four years, after which they expire and must be replaced.”

The fear is that if one company owns the local NBC and CBS affiliate in a large city, that company automatically will control a much larger percentage of the TV audience than any other station in the market. That can directly impact advertising rates charged by those stations, force other stations to consider similar mergers to maintain their market share, and leave many cities with two owners controlling the ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC stations in a market. That would also put independent stations at a marked disadvantage, unable to attract advertisers that will expect the audience numbers combined stations would get.

The group opposed to this rule also claimed that the FCC must reaffirm and defend the very existence of this rule during each regulatory review period, an argument that was also rejected by the court decision. A FCC hostile to the rule would likely not mount much of a defense to justify it.

The FCC’s Newest Loophole: Alleged Diversity

One FCC proposal that partly escaped criticism from the court was a new radio “incubator” program that would relax ownership limits for radio station owners participating in the project. The incubator program is designed to “support new and diverse entrants in the radio broadcasting industry by encouraging larger, experienced broadcasters to assist small, aspiring or struggling broadcasters that otherwise lack the financing or operational expertise necessary to own and operate a full-service radio station.”

One FCC proposal that partly escaped criticism from the court was a new radio “incubator” program that would relax ownership limits for radio station owners participating in the project. The incubator program is designed to “support new and diverse entrants in the radio broadcasting industry by encouraging larger, experienced broadcasters to assist small, aspiring or struggling broadcasters that otherwise lack the financing or operational expertise necessary to own and operate a full-service radio station.”

Critics contend the incubator program is a giant ownership limit loophole waiting to be exploited by large corporate station owners. Although initially protecting the new station’s independence for at least two years, the large corporate owner “helping” the new station become established can later buy the station, or manage the station’s programming and advertising inventory as soon as two years after the station gets on the air. Further, the corporate owner that will receive a waiver on station ownership limits for participating can ‘cash in’ that voucher in any market of “a similar proportion” to the one where the new station is launching. Most assumed that meant a market similar in size to population. But in fact it was defined as a market with a similar number of licensed radio stations.

The “market size” epic loophole would allow a corporate entity to set up a station in a relatively small sized city with a lot of licensed radio stations, such as Wilkes-Barre, Pa., which has 45, and take the resulting ownership waiver and “cash it in” by buying up a sixth extraordinarily valuable FM station in New York City, which has around 40 licensed stations on a very crowded radio dial.

The FCC attempted to place some limits on obvious loophole exploitation, like finding a front person to participate in the incubation program but allow the corporate “helper” to silently and secretly operate the station. But there are no obvious limits on allowing family members of corporate entities to participate. A similar loophole allowed Sinclair Broadcasting to acquire a significant number of additional TV stations above ownership caps by claiming they were in fact run independently by a family member of the CEO. There are multiple ways to abuse or exploit the program, but the court found the FCC gave adequate notice of the scope and rules of the project. The program’s impact on minority ownership was another matter, and the incubation program was put on hold as well because the FCC did not provide enough evidence of how the program would impact minority station ownership.

Judge Calls FCC’s Analysis Skills Insubstantial

“Problems abound with the FCC’s analysis,” Ambro wrote regarding the impact the FCC’s rules changes would have on minority ownership. “Most glaring is that, although we instructed it to consider the effect of any rule changes on female as well as minority ownership, the Commission cited no evidence whatsoever regarding gender diversity. It does not contest this. Instead it notes that ‘no data on female ownership was available’ and argues that it ‘reasonably relied on the data that was available and was not required to fund new studies.'”

“Problems abound with the FCC’s analysis,” Ambro wrote regarding the impact the FCC’s rules changes would have on minority ownership. “Most glaring is that, although we instructed it to consider the effect of any rule changes on female as well as minority ownership, the Commission cited no evidence whatsoever regarding gender diversity. It does not contest this. Instead it notes that ‘no data on female ownership was available’ and argues that it ‘reasonably relied on the data that was available and was not required to fund new studies.'”

Judge Ambro warned courts have frequently found certain FCC rules that were introduced without careful consideration of their impact are “arbitrary and capricious” and subject to be overturned at any time.

Ambro told the FCC it must do better.

“The only ‘consideration’ the FCC gave to the question of how its rules would affect female ownership was the conclusion there would be no effect. That was not sufficient, and this alone is enough to justify remand,” Ambro wrote. “Even just focusing on the evidence with regard to ownership by racial minorities, however, the FCC’s analysis is so insubstantial that it would receive a failing grade in any introductory statistics class.”

Ambro called the FCC’s analysis “woefully simplistic” because it attempted to use disparate data from two different federal agencies to measure minority ownership of broadcast stations, but the two entities asked different questions and used different methodologies.

“Attempting to draw a trendline between the [one agency’s data with another’s] is plainly an exercise in comparing apples to oranges, and the Commission does not seem to have recognized that problem or taken any effort to fix it,” Ambro complained.

Ambro also noted the FCC did not bother to estimate the number of minority-owned stations that would theoretically exist if the agency never changed its ownership rules.

Come Back to the Court With Your Homework… Finished

Judge Scirica

Ambro predicted an inevitable appeal of the court decision and additional litigation surrounding this week’s ruling. He warned the FCC that using the current majority to ram new rules through is not adequate and the FCC must prove the merits of its arguments if it wants to survive a court challenge. Ambro “remanded” or sent the proposed new rules back to the FCC to review and revise.

“On remand the Commission must ascertain on record evidence the likely effect of any rule changes it proposes and whatever ‘eligible entity’ definition it adopts on ownership by women and minorities, whether through new empirical research or an in depth theoretical analysis. If it finds that a proposed rule change would likely have an adverse effect on ownership diversity but nonetheless believes that rule in the public interest all things considered, it must say so and explain its reasoning,” Ambro wrote. “If it finds that its proposed definition for eligible entities will not meaningfully advance ownership diversity, it must explain why it could not adopt an alternate definition that would do so. Once again we do not prejudge the outcome of any of this, but the Commission must provide a substantial basis and justification for its actions whatever it ultimately decides.”

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai blasted the court decision and vowed an appeal, citing the partial dissent of Judge Anthony Joseph Scirica, who has consistently supported a number of the FCC’s deregulation efforts.

“For more than twenty years, Congress has instructed the Federal Communications Commission to review its media ownership regulations and revise or repeal those rules that are no longer necessary,” Pai said. “But for the last 15 years, a majority of the same Third Circuit panel has taken that authority for themselves, blocking any attempt to modernize these regulations to match the obvious realities of the modern media marketplace. It’s become quite clear that there is no evidence or reasoning — newspapers going out of business, broadcast radio struggling, broadcast TV facing stiffer competition than ever — that will persuade them to change their minds. We intend to seek further review of today’s decision and are optimistic that the views set forth today in Judge Scirica’s well-reasoned opinion ultimately will carry the day.”

Subscribe

Subscribe United States Circuit Judge Thomas L. Ambro has sat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit hearing countless legal challenges of federal government rules, regulations, and laws since 2000. In fact, he has heard so many cases it might have worried petitioners when he opened his majority-held ruling with the words “Here we are again.”

United States Circuit Judge Thomas L. Ambro has sat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit hearing countless legal challenges of federal government rules, regulations, and laws since 2000. In fact, he has heard so many cases it might have worried petitioners when he opened his majority-held ruling with the words “Here we are again.”

The FCC itself later admitted that the consolidation frenzy caused negative effects that should be addressed. But the incoming George W. Bush Administration initially had other ideas and under the leadership of FCC Chairman Michael Powell, the majority of Republicans on the Commission supported further relaxation of ownership rules. In early 2003, the FCC held a single public hearing on the matter, which sparked outrage among many Americans concerned about the impact media consolidation had already had on their local stations. By June of that year, nearly two million letters from the public opposing further media consolidation had arrived at the FCC. The Commission, despite the public outcry, ultimately voted 3-2 to repeal a long-standing ban prohibiting a local newspaper from also owning a local television station (or vice versa) and also relaxed other ownership rules, claiming they were no longer necessary to protect competition, localism, or ownership diversity.

The FCC itself later admitted that the consolidation frenzy caused negative effects that should be addressed. But the incoming George W. Bush Administration initially had other ideas and under the leadership of FCC Chairman Michael Powell, the majority of Republicans on the Commission supported further relaxation of ownership rules. In early 2003, the FCC held a single public hearing on the matter, which sparked outrage among many Americans concerned about the impact media consolidation had already had on their local stations. By June of that year, nearly two million letters from the public opposing further media consolidation had arrived at the FCC. The Commission, despite the public outcry, ultimately voted 3-2 to repeal a long-standing ban prohibiting a local newspaper from also owning a local television station (or vice versa) and also relaxed other ownership rules, claiming they were no longer necessary to protect competition, localism, or ownership diversity. The FCC’s ability to ram through the rules changes, despite public opposition, was immediately met with a formidable 2003 court challenge by the Prometheus Radio Project, a non-profit advocacy and community organizing group that opposed corporate consolidation of radio stations and supported the low-power (LPFM) radio movement, which sought low-cost licensing of community radio stations to preserve localism and provide diverse radio programming.

The FCC’s ability to ram through the rules changes, despite public opposition, was immediately met with a formidable 2003 court challenge by the Prometheus Radio Project, a non-profit advocacy and community organizing group that opposed corporate consolidation of radio stations and supported the low-power (LPFM) radio movement, which sought low-cost licensing of community radio stations to preserve localism and provide diverse radio programming. An exasperated Judge Ambro repeatedly took the FCC (and indirectly Ajit Pai, the current chairman) to task for ignoring the Court’s instructions on formulating media ownership policies that would survive court challenges.

An exasperated Judge Ambro repeatedly took the FCC (and indirectly Ajit Pai, the current chairman) to task for ignoring the Court’s instructions on formulating media ownership policies that would survive court challenges. One FCC proposal that partly escaped criticism from the court was a new radio “incubator” program that would relax ownership limits for radio station owners participating in the project. The incubator program is designed to “support new and diverse entrants in the radio broadcasting industry by encouraging larger, experienced broadcasters to assist small, aspiring or struggling broadcasters that otherwise lack the financing or operational expertise necessary to own and operate a full-service radio station.”

One FCC proposal that partly escaped criticism from the court was a new radio “incubator” program that would relax ownership limits for radio station owners participating in the project. The incubator program is designed to “support new and diverse entrants in the radio broadcasting industry by encouraging larger, experienced broadcasters to assist small, aspiring or struggling broadcasters that otherwise lack the financing or operational expertise necessary to own and operate a full-service radio station.” “Problems abound with the FCC’s analysis,” Ambro wrote regarding the impact the FCC’s rules changes would have on minority ownership. “Most glaring is that, although we instructed it to consider the effect of any rule changes on female as well as minority ownership, the Commission cited no evidence whatsoever regarding gender diversity. It does not contest this. Instead it notes that ‘no data on female ownership was available’ and argues that it ‘reasonably relied on the data that was available and was not required to fund new studies.'”

“Problems abound with the FCC’s analysis,” Ambro wrote regarding the impact the FCC’s rules changes would have on minority ownership. “Most glaring is that, although we instructed it to consider the effect of any rule changes on female as well as minority ownership, the Commission cited no evidence whatsoever regarding gender diversity. It does not contest this. Instead it notes that ‘no data on female ownership was available’ and argues that it ‘reasonably relied on the data that was available and was not required to fund new studies.'”

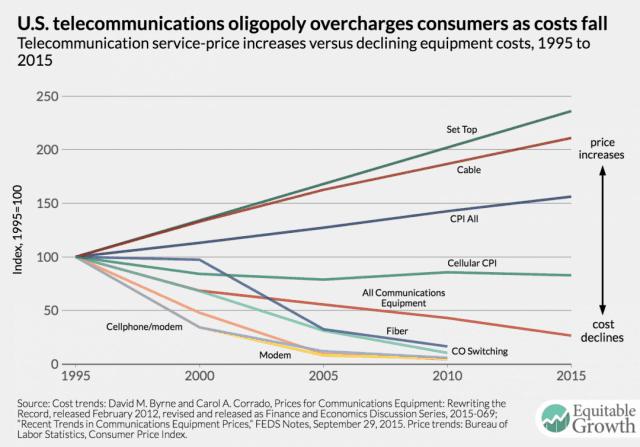

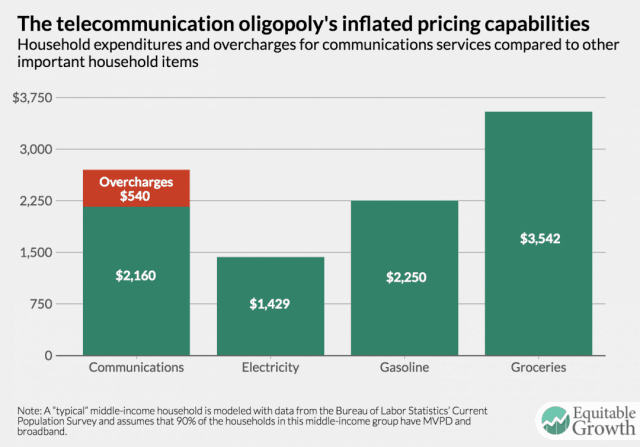

The original premise of the 1996 Telecom Act was that it would eliminate regulations that discouraged competition. Promoters of the legislation asked why there should only be one phone or cable company in each city and why maintain regulations that kept cable and phone companies out of each others’ markets. Fears about market power and allowing domineering cable and phone companies to grow even larger were dismissed on the premise that a wide open marketplace, with regulations in place to protect consumers and competition would avoid creating telecom robber barons.

The original premise of the 1996 Telecom Act was that it would eliminate regulations that discouraged competition. Promoters of the legislation asked why there should only be one phone or cable company in each city and why maintain regulations that kept cable and phone companies out of each others’ markets. Fears about market power and allowing domineering cable and phone companies to grow even larger were dismissed on the premise that a wide open marketplace, with regulations in place to protect consumers and competition would avoid creating telecom robber barons. Some of the bill’s industry backers were also there, some who would ironically see its signing as directly responsible for the eventual demise of their independent companies. John Hendricks of the Discovery Channel, Glenn Jones of Jones Intercable (acquired by Comcast in 1999), Jean Monty of Northern Telecom (later Nortel), Donald Newhouse of Advance Publications (eventual part owner of Bright House Networks and later Charter Communications), William O’Shea of Reuters Ltd. and Ray Smith of Bell Atlantic (today part of Verizon) were on hand. Also in the audience was Jack Valenti of the Motion Picture Association of America, representing Hollywood Studios.

Some of the bill’s industry backers were also there, some who would ironically see its signing as directly responsible for the eventual demise of their independent companies. John Hendricks of the Discovery Channel, Glenn Jones of Jones Intercable (acquired by Comcast in 1999), Jean Monty of Northern Telecom (later Nortel), Donald Newhouse of Advance Publications (eventual part owner of Bright House Networks and later Charter Communications), William O’Shea of Reuters Ltd. and Ray Smith of Bell Atlantic (today part of Verizon) were on hand. Also in the audience was Jack Valenti of the Motion Picture Association of America, representing Hollywood Studios. For example, lawmakers insisted on unbundling telecommunications network elements, an arcane way of saying new competitors must be granted access to existing networks to be shared at wholesale rates. In practice, this meant if a phone company entered the internet service provider business, it must also make its network available for other ISPs as well. In some areas, competing local telephone companies also offered landline service over existing telephone lines, paying wholesale connection fees to the incumbent local phone company. As competition emerged, the incumbent company usually petitioned for a lifting of the regulations governing their business, claiming competition had arrived.

For example, lawmakers insisted on unbundling telecommunications network elements, an arcane way of saying new competitors must be granted access to existing networks to be shared at wholesale rates. In practice, this meant if a phone company entered the internet service provider business, it must also make its network available for other ISPs as well. In some areas, competing local telephone companies also offered landline service over existing telephone lines, paying wholesale connection fees to the incumbent local phone company. As competition emerged, the incumbent company usually petitioned for a lifting of the regulations governing their business, claiming competition had arrived.

The country’s largest cable industry lobbying group has decided to drop the word “cable” from its name, rebranding itself NCTA – The Internet & Television Association.

The country’s largest cable industry lobbying group has decided to drop the word “cable” from its name, rebranding itself NCTA – The Internet & Television Association.