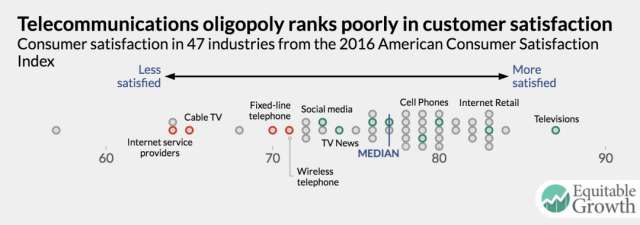

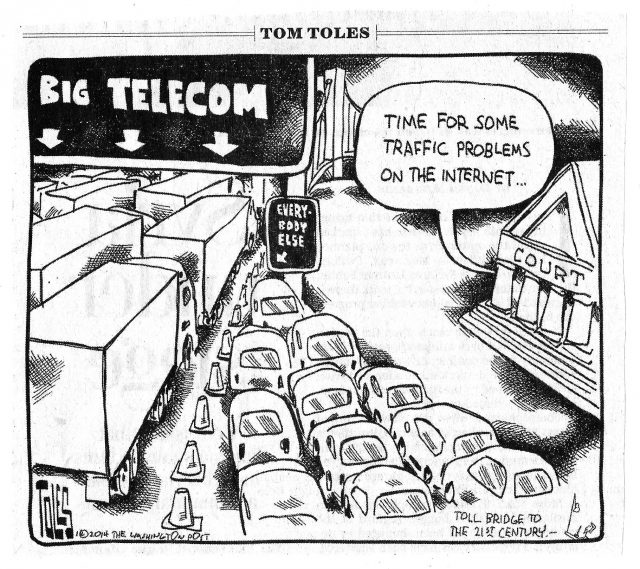

Copps (Image: Peretz Partensky)

Former interim FCC chairman and commissioner Michael Copps has become so disillusioned with the agenda of the Trump Administration’s FCC, he’s ready to conclude its current leadership under Chairman Ajit Pai represents the worst FCC ever.

In an effort to erase the Obama Administration, President Trump has made it a priority to actively reverse the former administration’s policies. The FCC is no exception, and according to an article published by Moyers & Co., the Republican majority running the FCC these days are actively on board White House strategist Steve Bannon’s campaign to “deconstruct the administrative state.”

Author Michael Winship calls Pai an enthusiastic supporter of Donald Trump’s “doctrine of regulatory devastation,” and it appears Copps agrees as he comments on the current FCC agenda to dismantle set-top box competition, Net Neutrality, Lifeline internet service for the poor, restricting media consolidation, consumer’s privacy rights, and general oversight of the telecom industry.

Pai’s Garbage

“I think the April 26 speech that Ajit Pai gave at the Newseum, which was partially funded, I think, by conservative activist causes, was probably the worst speech I’ve ever heard a commissioner or a chairman of the FCC give,” Copps said. “It was replete with distorted history and a twisted interpretation of judicial decisions. And then, about two-thirds of the way through, it became intensely political and ideological, and he was spouting all this Ronald Reagan nonsense — if the government is big enough to do what you want, it’s big enough to take away everything you have, and all that garbage. It was awful. It’s maybe the worst FCC I’ve ever seen or read about.”

Today, Copps is special adviser for the Media and Democracy Reform Initiative at the nonpartisan grassroots organization Common Cause. He “just may be,” Bill Moyers once said, “the most knowledgeable fellow in Washington on how communications policy affects you and me.”

Ajit Pai at Newseum, Apr. 26, 2017 (Image: C-SPAN)

Under the Trump Administration, Copps believes we are watching a wholesale transfer of the most important tools in a democracy — real news, diversity of ideas, and access to an open internet into the hands of a handful of mega-corporations and special interests that have bankrolled the Republican party and the election of Donald Trump.

“This is not populism; this is a plutocracy,” Copps warned. “Trump has surrounded himself with millionaires and billionaires, plus some ideologues who believe in, basically, no government. And the Trump FCC already has been very successful in dismantling lots of things — not just the Net Neutrality that they’re after now, but privacy, and Lifeline, which is subsidized broadband for those who can’t afford it. And just all sorts of things up and down the line. The whole panoply of regulation and public interest oversight — if they could get rid of it all, they would; if they can, they will.”

In fact, Copps noted, there were several conservative advisers on Trump’s transition team that advocated abolishing the FCC outright, believing consolidated telecom companies and media empires can successfully regulate themselves.

“I don’t know if Donald Trump is good for the country. but he’s damn good for CBS.”

“[CBS CEO Les] Moonves said it best: ‘I don’t know if Donald Trump is good for the country. but he’s damn good for CBS,'” Copps said. “The election was just a glorified reality show and I do not think it was an aberration. Until we get that big picture straightened out and we get a civic dialogue that’s worthy of the American people and that actually advances citizens’ ability to practice the art of self-government — that informs citizens so they can cast intelligent votes and we stop making such damn-fool decisions — we’re in serious trouble.”

Copps complained the mainstream media isn’t even covering stories about digital democracy, instead preoccupied with 24/7 coverage of the circus in Washington, D.C.

Copps complained the mainstream media isn’t even covering stories about digital democracy, instead preoccupied with 24/7 coverage of the circus in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t think right now that commercial media is going to fix itself or even that we can save it with any policy that’s likely in the near-term, so we have to start looking at other alternatives,” Copps advised. “We have to talk about public media — public media probably has to get its act together somewhat, too. It’s not everything that Lyndon Johnson had in mind back in 1967 [when the Public Broadcasting Act was signed], but it’s still the jewel of our media ecosystem. So I’m more worried than ever about the state of our media — not just fake news but the lack of real news.”

Exposing what is really going on in Washington these days requires reporting beyond the latest misstep or tweet from the president, says Copps. For him, it’s the pervasive influence of corporate cash that really matters.

“I think there is that right-wing, pro-business, invisible hand ideology, and then there’s just the unabashed and unprecedented and disgusting level of money in politics,” Copps said. “I don’t blame just the Republicans; the Democrats are just about as beholden to it, too.”

Pai is a True Believer

Copps believes Pai is a true believer of an ideology that regulations do more harm than good.

Copps believes Pai is a true believer of an ideology that regulations do more harm than good.

“He has this Weltanschauung [world view] or whatever you want to call it that is so out of step with modern politics and where we should be in the history of this country that it’s potentially extremely destructive,” Copps said. “And Michael O’Rielly, the other Republican commissioner, is about the same. He’s an ideologue, too.”

“The problem is that Republicans inside the Beltway are joined in lockstep opposition on almost all these issues, and the level of partisanship, lobbying, big money, and ideology have thus far been insurmountable obstacles,” said Copps. “But I believe if members of Congress spent more time at home, holding more town hall meetings, they would quickly learn that many, many of their constituents are on the pro-consumer, pro-citizen side of these issues.”

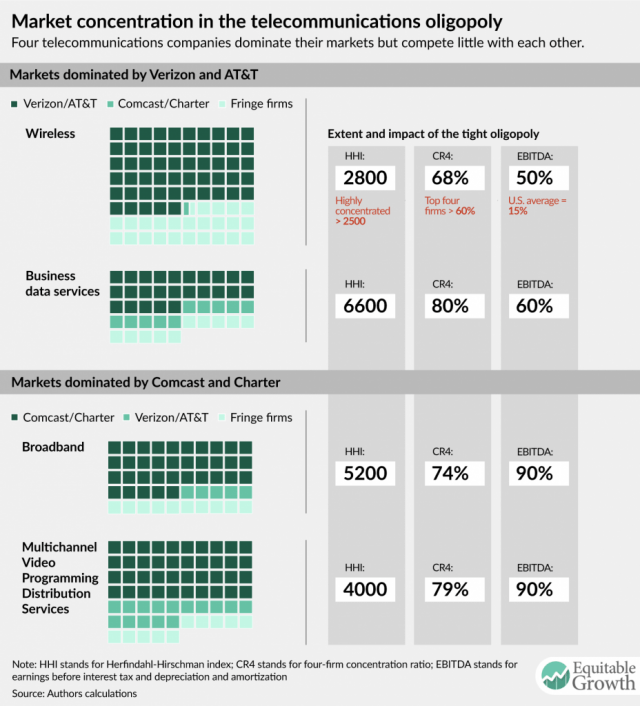

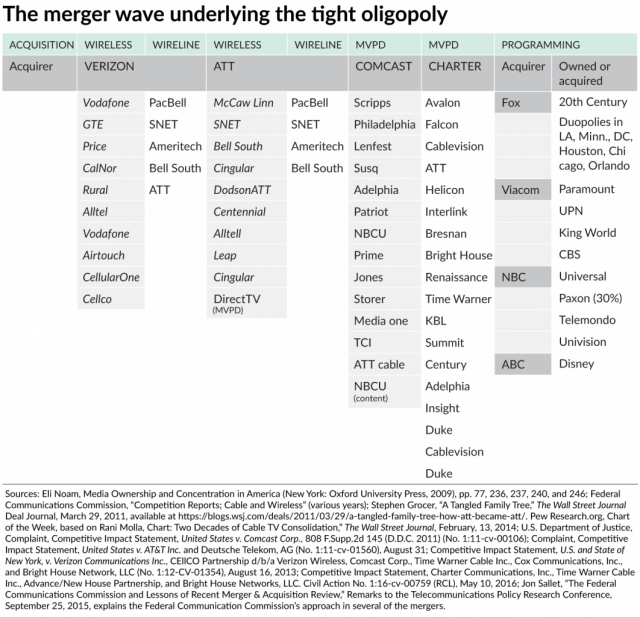

Copps is worried that prior mergers set precedents for even larger ones, and the ongoing consolidation of the media and telecom industry is only going to get worse under the Trump Administration.

“I don’t know how long you can let this go on. How long can you open the bazaar to all this consolidation, how much can you encourage all this commercialization, how much can you ignore public media until you get to the point of no return where you can’t really fix it anymore,” Copps asked. “And I also think that the national discourse on the future of the internet has really suffered while we play ping pong with Net Neutrality; one group comes in, does this, the other group, comes in and reverses it, boom, boom, boom. And Net Neutrality is not the salvation or the solution to all of the problems of the internet. As you know, it’s kind of the opening thing you have to have, it lays a foundation where we can build a truly open internet.”

“It’s all about the ideology, the world of big money, the access that the big guys have and continue to have,” Copps concluded. “It’s not that the FCC outright refuses to let public interest groups through the door or anything like that; it’s just the lack of resources citizens and public interest groups have compared to what the big guys have. The public interest groups don’t have much of a chance, but I think they’ve done a pretty good job given the lack of resources.”

What Should the Public Do?

“Figure out how you really make this a grass-roots effort — and not just people writing, in but people doing more than that,” Copps advised. “In July, we will have a day devoted to internet action, so stay tuned on that. In addition, as Bill Moyers says, ‘If you can sing, sing. If you can write a poem, write a poem.’ Different initiatives attract different audiences, so whatever you can do, do. John Oliver made a huge difference in getting us to Net Neutrality and now he’s helping again. If you went up to the Hill right after that first John Oliver show on Net Neutrality [in 2014], you saw immediately that it made a difference with the members and the staff. There’s no one silver bullet, no “do this” and it suddenly happens. You just have to do whatever you can do to get people excited and organized. It’s as simple as that.”

Three unnamed sources told the New York Post Charter Communications is seeking to acquire privately held Cox Communications, despite repeated assertions from the family owned Cox it is not for sale.

Three unnamed sources told the New York Post Charter Communications is seeking to acquire privately held Cox Communications, despite repeated assertions from the family owned Cox it is not for sale. Cox told the newspaper all of this attention is unwanted.

Cox told the newspaper all of this attention is unwanted.

Subscribe

Subscribe