Big Telecom companies like Verizon and AT&T use phony numbers and perpetuate myths about broadband traffic and network investments that have conned investors out of at least $1 trillion in unnecessary investments and consolidation.

Big Telecom companies like Verizon and AT&T use phony numbers and perpetuate myths about broadband traffic and network investments that have conned investors out of at least $1 trillion in unnecessary investments and consolidation.

Alexander Goldman, former chief analyst for CTI’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grants, is warning Wall Street and investors they are at risk of losing millions more because some of the largest telecom companies in the country are engaged in disseminating bad math and conventional wisdom that relies more on repetition of their talking points than actual facts.

Goldman’s editorial, published by Broadband Breakfast, believes the campaign of misinformation is perpetuated by a media that accepts industry claims without examining the underlying facts and a pervasive echo chamber that delivers credibility only by the number of voices saying then same thing.

Goldman takes Verizon Communications CEO Lowell McAdam to task for an editorial published in 2013 in Verizon’s effort to beat back calls on regulators to oversee the broadband industry and correct some of its anti-competitive behavior.

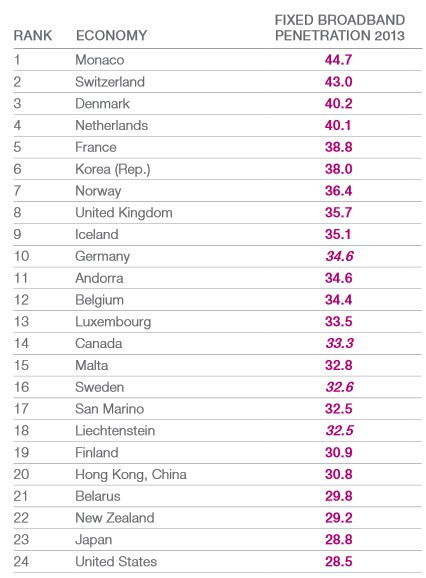

McAdam claimed the U.S. built a global lead in broadband on investments of $1.2 trillion over 17 years to deploy “next generation broadband networks” because networks were deregulated.

Setting aside the fact the United States is not a broadband leader and continues to be outpaced by Europe and Asia, Goldman called McAdam’s impressive-sounding dollar figures meaningless, considering over the span of that 17 years, the United States progressed from dial-up to fiber broadband. Wired networks have been through a generational change that required infrastructure to be replaced and wireless networks have been through at least two significant generations of change over that time — mandatory investments that would have occurred with or without deregulation.

Over the past 17 years, the industry has gotten more of its numbers wrong than right. An explosion of fiber construction in the late 1990s based on predictions of data tsunamis turned out to be catastrophically wrong. University of Minnesota professor Andrew Odlyzko, the worst enemy of the telecom industry talking point, has been debunking claims of broadband traffic jams and the need to implement usage-based pricing and speed throttling for years. In 1998, when Wall Street was listening intently to forecasts produced by self-interested telecom companies like Worldcom that declared broadband traffic was going to double every 100 days, Odlyzko was telling his then-employer AT&T is was all a lot of nonsense. The broadband traffic emperor had no clothes, and statistics from rival telecom companies suggested Worldcom was telling tall tales. But AT&T executives didn’t listen.

“We just have to try harder to match those growth rates and catch up with WorldCom,” AT&T executives told Odlyzko and his colleagues, believing the problem was simply ineffective sales, not real broadband demand. When sales couldn’t generate those traffic numbers and Wall Street analysts began asking why, companies like Global Crossing and Qwest resorted to “hollow swaps” and other dubious tricks to fool analysts, prop up the stock price and executive bonuses, and invent sales.

“We just have to try harder to match those growth rates and catch up with WorldCom,” AT&T executives told Odlyzko and his colleagues, believing the problem was simply ineffective sales, not real broadband demand. When sales couldn’t generate those traffic numbers and Wall Street analysts began asking why, companies like Global Crossing and Qwest resorted to “hollow swaps” and other dubious tricks to fool analysts, prop up the stock price and executive bonuses, and invent sales.

Nobody bothered to ask for an independent analysis of the traffic boom that wasn’t. Wall Street and investors saw dollars waiting to be made, if only providers had the networks to handle the traffic. This began the fiber boom of the late 1990s, “an orgy of construction” as The Economist called it, all to prepare for a tidal wave of Internet traffic that never arrived.

After companies like Global Crossing and Worldcom failed in the biggest bankruptcies the country had ever seen at the time, Odlyzko believes important lessons were never learned. He blames Worldcom executives for inflating the Internet bubble more than anyone.

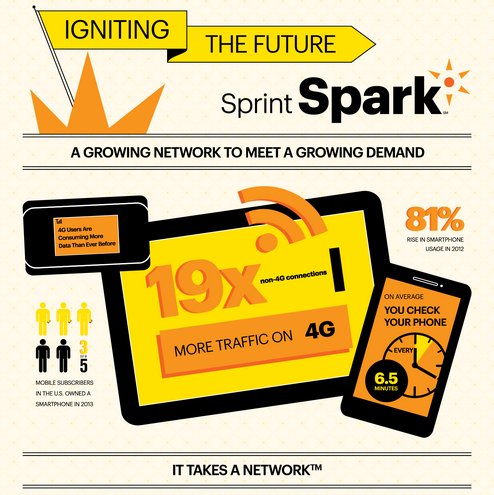

A bubble of another kind is forming today in America’s wireless industry, fueled by pernicious predictions of a growing spectrum crisis to anyone in DC willing to listen and hurry up spectrum auctions. Both AT&T and Verizon try to stun investors and politicians with enormous dollar numbers they claim are being spent to hurry upgraded wireless networks ready to handle an onslaught of high bandwidth wireless video. Both Verizon’s McAdam and AT&T’s Randall Stephenson intimidate Washington politicians with subtle threats that any enactment of industry reforms by the FCC or Congress will threaten the next $1.2 trillion in network investments, jobs, and America’s vital telecom infrastructure.

Odlyzko has seen this parade before, and he is not impressed. Streaming video on wireless networks is effectively constrained by miserly usage caps, not network capacity, and to Odlyzko, the more interesting story is Americans are abandoning voice calling for instant messages and texting.

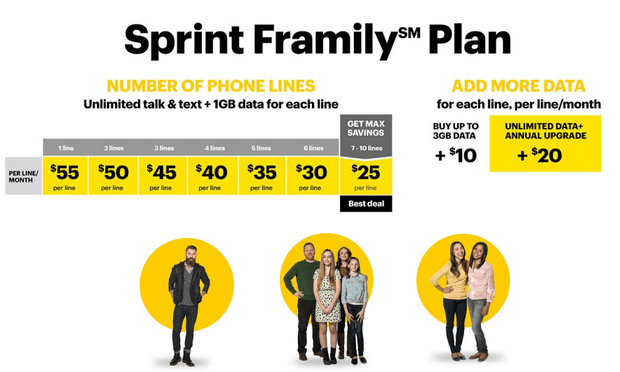

That isn’t a problem for wireless carriers because texting is where the real money is made. Odlyzko notes that wireless carriers profit an average of $1,000 per megabyte for text messages, usually charged per-message or through subscription plan add ons or as part of a bundle. Cellular voice calling is much less profitable, earning about $1 per megabyte of digitized traffic.

That isn’t a problem for wireless carriers because texting is where the real money is made. Odlyzko notes that wireless carriers profit an average of $1,000 per megabyte for text messages, usually charged per-message or through subscription plan add ons or as part of a bundle. Cellular voice calling is much less profitable, earning about $1 per megabyte of digitized traffic.

Wireless carriers in the United States, particularly Verizon and AT&T, are immensely profitable and the industry as a whole haven’t invested more than 27% of their yearly revenue on network upgrades in over a decade. In fact, in 2011 carriers invested just 14.9% of their revenue, rising slightly to 16.3 percent in 2012 when companies collectively invested $30 billion on network improvements, but earned $185 billion along the way.

While Verizon preached “spectrum crisis” to the FCC and Congress and claimed it was urgently prioritizing network upgrades, company executives won approval of a plan to pay Vodafone, then a part owner of Verizon Wireless, $130 billion to buy them out. That represents the collective investment of every wireless provider in the country in network upgrades from 2005-2012. Verizon Wireless cannot find the money to upgrade their wireless networks to deliver customers a more generous data allowance (or an unlimited plan), but it had no trouble approving $130 billion to buy out its partner so it could keep future profits to itself.

Odlyzko concludes the obvious: “modern telecom is less about high capital investments and far more a game of territorial control, strategic alliances, services, and marketing, than of building a fixed infrastructure.”

That is why there is no money for Verizon FiOS expansion but there was plenty to pay Vodafone, and its executives who walked away with executive bonuses totaling $89.6 million.

As long as American wireless service remains largely in the hands of AT&T and Verizon Wireless, competition isn’t likely to seriously dent prices or profits. At least investors who are buying Verizon’s debt hope so.

Goldman again called attention to Odlyzko’s latest warning that the industry has its numbers (and priorities) wrong, and the last time Odlyzko had the numbers right and the telecommunications industry got its numbers wrong, telecommunications investors lost $1 trillion in the telecommunications dot.com bust.

As the drumbeat continues for further wireless consolidation and spectrum acquisition, investors have been told high network costs necessitate combining operations to improve efficiency and control expenses. Except the biggest costs faced by wireless carriers like Verizon are to implement strategic consolidation opportunities like the Vodafone deal, not maintain and grow their wireless network. AT&T is putting much of its spending in a proposed acquisition of DirecTV this year as well — at a cost of $48.5 billion. That could buy a lot of new cell towers and a much more consumer-friendly data plan.

Voice to text substitution (US)

| year | voice minutes billions | texts billions |

| 2005 | 1,495 | 81 |

| 2006 | 1,798 | 159 |

| 2007 | 2,119 | 363 |

| 2008 | 2,203 | 1,005 |

| 2009 | 2,275 | 1,563 |

| 2010 | 2,241 | 2,052 |

| 2011 | 2,296 | 2,304 |

| 2012 | 2,300 | 2,190 |

Cell phone network companies (if you can believe their SEC filings) are incredibly profitable, and are spending relatively little on infrastructure:

| year | revenues in $ billions | capex in $ billions | capex/revenues |

| 2004 | 102.1 | 27.9 | 27.3% |

| 2005 | 113.5 | 25.2 | 22.2 |

| 2006 | 125.5 | 24.4 | 19.4 |

| 2007 | 138.9 | 21.1 | 15.2 |

| 2008 | 148.1 | 20.2 | 13.6 |

| 2009 | 152.6 | 20.4 | 13.3 |

| 2010 | 159.9 | 24.9 | 15.6 |

| 2011 | 169.8 | 25.3 | 14.9 |

| 2012 | 185.0 | 30.1 | 16.3 |

Subscribe

Subscribe

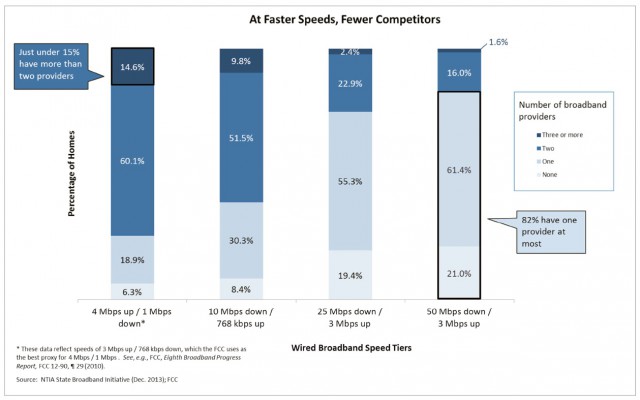

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.”

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.” Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition.

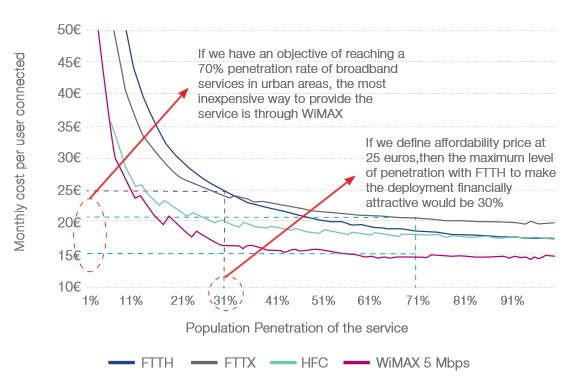

Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition. Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service.

Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service.