Providers’ tall tales.

Year after year, equipment manufacturers and internet service providers trot out predictions of a storm surge of internet traffic threatening to overwhelm the internet as we know it. But growing evidence suggests such scare stories are more about lining the pockets of those predicting traffic tsunamis and the providers that use them to justify raising your internet bill.

This month, Cisco — one of the country’s largest internet equipment suppliers, released its latest predictions of astounding internet traffic growth. The company is so confident its annual predictions of traffic deluges are real it branded a term it likes to use to describe it: The Zettabyte Era. (A zettabyte, for those who don’t know, is one sextillion bytes, or perhaps more comfortably expressed as one trillion gigabytes.)

Cisco’s business thrives on scaring network engineers with predictions that customers will overwhelm their broadband networks unless they upgrade their equipment now, as in ‘right now!‘ In turn, the broadband industry’s bean counters find predictions of traffic explosions useful to justify revenue enhancers like usage caps, usage-based billing, and constant rate increases.

“As we make these and other investments, we periodically need to adjust prices due to increases [in] business costs,” wrote Comcast executive Sharon Powell in a letter defending a broad rate increase imposed on customers in Philadelphia late last year.

In 2015, as that cable company was expanding its usage caps to more markets, spokesman Charlie Douglas tried to justify the usage caps claiming, “When you have 10 percent of the customers consuming 50 percent of the network bandwidth, it’s only fair that those consumers should pay more.”

When Cisco released its 2017 predictions of internet traffic growth, once again it suggests a lot more data will need to be accommodated across America’s broadband and wireless networks. But broadband expert Dave Burstein has a good memory based on his long involvement in the industry and the data he saw from Cisco actually deflates internet traffic panic, and more importantly provider arguments for higher cost, usage-capped internet access.

When Cisco released its 2017 predictions of internet traffic growth, once again it suggests a lot more data will need to be accommodated across America’s broadband and wireless networks. But broadband expert Dave Burstein has a good memory based on his long involvement in the industry and the data he saw from Cisco actually deflates internet traffic panic, and more importantly provider arguments for higher cost, usage-capped internet access.

“Peak Internet growth may have been a couple of years ago,” wrote Burstein. “For more than a decade, internet traffic went up ~40% every year. Cisco’s VNI, the most accurate numbers available, sees growth this year down to 27% on landlines and falling to 15-20% many places over the next few years. Mobile growth is staying higher — 40-50% worldwide. Fortunately, mobile technology is moving even faster. With today’s level of [provider investments], LTE networks can increase capacity 10x to 15x.”

According to Burstein, Cisco’s estimates for mobile traffic in the U.S. and Canada in 2020 is 4,525 petabytes and in 2021 is 5,883 petabytes. That’s a 30% growth rate. Total consumer traffic in the U.S. and Canada Cisco sees as 48,224 petabytes and 56,470 petabytes in 2021. That’s a 17% growth rate, which is much lower on wired networks.

Burstein’s findings are in agreement with those of Professor Andrew Odlyzko, who has debunked “exaflood/data tsunami” scare stories for over a decade.

“[The] growth rate has been decreasing for almost two decades,” Odlyzko wrote in a 2016 paper published in IPSI BgD Transactions. “Even the growth rate in wireless data, which was extremely high in the last few years, shows clear signs of a decline. There is still rapid growth, but it is simply not at the rates observed earlier, or hoped for by many promoters of new technologies and business methods.”

Burstein

The growth slowdown, according to Odlyzko, actually began all the way back in 1997, providing the first warning the dot.com bubble of the time was preparing to burst. He argued the data models used by equipment manufacturers and the broadband industry to measure growth have been flawed for a long time.

When new internet trends became popular, assumptions were made about what impact they would have, but few models accurately predicted whether those trends would remain a major factor for internet traffic over the long-term.

Peer-to-peer file sharing, one of the first technologies Comcast attempted to use as a justification for its original 250GB usage cap, is now considered almost a footnote among the applications having a current profound impact on internet traffic. Video game play, also occasionally mentioned as a justification for usage caps or network management like speed throttling, was hardly ever a major factor for traffic slowdowns, and most games today exchange player actions using the smallest amount of traffic possible to ensure games are fast and responsive. In fact, the most impact video games have on the internet is the size of downloads required to acquire and update them.

Odlyzko also debunked alarmist predictions of traffic overloads coming from the two newest and largest traffic contributors of the period 2001-2010 — cloud backups and online video.

Odlyzko

“Actual traffic trends falsified this conjecture, as the first decade of the 21st century witnessed a substantial [traffic growth rate] slowdown,” said Odlyzko. “The frequent predictions about ‘exafloods’ overwhelming the networks that were frequent a decade ago have simply not come to pass. At the 20 to 30% per year growth rates that are observed today in industrialized countries, technology is advancing faster than demand, so there is no need for increasing the volume of investments, or for the fine-grained traffic control schemes that are beloved by industry managers as well as researchers.”

That’s a hard pill to swallow for companies that manufacture equipment designed to “manage,” throttle, cap, and charge customers based on their overusage of the internet. It also gives fits to industry executives, lobbyists, and the well paid public policy researchers that produce on spec studies and reports attempting to justify such schemes. But the numbers don’t lie, even if the industry does.

Although a lot of growth measured these days comes from wireless networks, they are not immune to growth slowdowns either. The arrival of the smartphone was hailed by wireless companies and Wall Street as a rocket engine to propel wireless revenue sky high. Company presidents even based part of their business plans on revenue earned from monetizing data usage allegedly to pay for spectrum acquisitions and upgrades.

McAdam

Verizon’s CEO Lowell McAdam told investors as late as a year ago “unlimited data” could never work on Verizon Wireless again.

“With unlimited, it’s the physics that breaks it,” he said. “If you allow unlimited usage, you just run out of gas.”

The laws of physics must have changed this year when Verizon reintroduced unlimited data for its wireless customers.

John Wells, then vice president of public affairs for CTIA, the wireless industry’s top lobbying group, argued back in 2010 AT&T’s decision to establish pricing tiers was a legitimate way for carriers to manage the ‘explosive growth in data usage.’ Wells complained the FCC was taking too long to free up critically needed wireless spectrum, so they needed “other tools” to manage their networks.

“This is one of the measures that carriers are considering to make sure everyone has a fair and equal experience,” Walls said, forgetting to mention the wireless industry was cashing in on wireless data revenue, which increased from $8.5 billion annually in 2005 to $41.5 billion in 2009, and Wall Street was demanding more.

“There were again many cries about unsustainable trends, and demands for more spectrum (even though the most ambitious conceivable re-allocation of spectrum would have at most doubled the cellular bands, which would have accommodated only a year of the projected 100+% annual growth),” Odlyzko noted.

What the industry and Wall Street did not fully account for is that their economic models and pricing had the effect of modifying consumer behavior and changed internet traffic growth rates. Odlyzko cites the end of unlimited data plans and the introduction of “tight data caps” as an obvious factor in slowing down wireless traffic growth.

“But there were probably other significant ones,” Odlyzko wrote. “For example, mobile devices have to cope not just with limited transmission capacity, but also with small screens, battery

limits, and the like. This may have led to changes of behavior not just of users, but also of app developers. They likely have been working on services that can function well with modest

bandwidth.”

“U.S. wireless data traffic, which more than doubled from 2012 to 2013, increased just 26% from 2013 to 2014,” Odylzko reported. “This was a surprise to many observers, especially since there is still more than 10 times as much wireline Internet traffic than wireless Internet traffic.”

“U.S. wireless data traffic, which more than doubled from 2012 to 2013, increased just 26% from 2013 to 2014,” Odylzko reported. “This was a surprise to many observers, especially since there is still more than 10 times as much wireline Internet traffic than wireless Internet traffic.”

Many believe that was around the same time smartphones achieved peak penetration in the marketplace. Virtually everyone who wanted a smartphone had one by 2014, and as a result of fewer first-time users on their networks, data traffic growth slowed. At the same time, some Wall Street analysts also began to worry the companies were reaching peak revenue per user, meaning there was nothing significant to sell wireless customers that they didn’t already have. At that point, future revenue growth would come primarily from rate increases and poaching customers from competitors. Or, as some providers hoped, further monetizing data usage.

The Net Neutrality debate has kept most companies from “innovating” with internet traffic “fast lanes” and other monetization schemes out of fear of stoking political blowback. Wireless companies could make significant revenue trying to sell customers performance boosters like higher priority access on a cell tower or avoiding a speed throttle that compromised video quality. But until providers have a better idea whether the current administration’s efforts to neuter Net Neutrality are going to be successful, some have satisfied themselves with zero rating schemes and bundling that offer customers content without a data caps or usage billing or access to discounted packages of TV services like DirecTV Now.

Verizon is also betting its millions that “content is king” and the next generation of revenue enhancers will come from owning and distributing exclusive video content it can offer its customers.

Odlyzko believes providers are continuing the mistake of stubbornly insisting on acquiring or at least charging content providers for streaming content across their networks. That debate began more than a decade ago when then SBC/AT&T CEO Edward Whitacre Jr. insisted content companies like Netflix were not going to use AT&T’s “pipes for free.”

“Much of the current preoccupation of telecom service providers with content can be explained away as following historical precedents, succumbing to the glamour of ‘content,'” Odlyzko wrote. “But there is likely another pressing reason that applies today. With connection speeds growing, and the ability to charge according to the value of traffic being constrained either directly by laws and regulations, or the fear of such, the industry is in a desperate search for ways not to be a ‘dumb pipe.'”

AT&T and Verizon: The Doublemint Twins of Wireless

A number of Wall Street analysts also fear common carrier telecom companies are a revenue growth ‘dead-end,’ offering up a commodity service about as exciting as electricity. Customers given a choice between AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, or T-Mobile need something to differentiate one network from the other. Verizon Wireless claims it has a best in class LTE network with solid rural coverage. AT&T offers bundling opportunities with its home broadband and DirecTV satellite service. Sprint is opting to be the low price leader, and T-Mobile keeps its customers with a network that outperforms expectations and pitches constant promotions and giveaways to customers that crave constant gratification and change.

The theory goes that acquiring video content will drive data usage revenue, further differentiate providers, and keep customers from switching to a competitor. But Odylzko predicts these acquisitions and offerings will ultimately fail to make much difference.

“Dumb pipes’ [are] precisely what society needs,” Odylzko claims and in his view it is the telecom industry alone that has the “non-trivial skills” required to provide ubiquitous reliable broadband. The industry also ignores the utility-like built-in advantage it has owning pre-existing wireline and wireless networks. The amortized costs of network infrastructure often built decades ago offers natural protection from marketplace disruptors that likely lack the fortitude to spend billions of dollars required to invade markets with newly constructed networks of their own.

Odylzko is also critical of the industry’s ongoing failure of imagination.

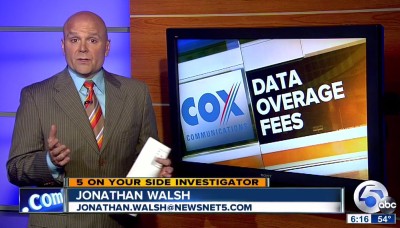

Stop the Cap! calls that the industry’s “broadband scarcity” business model. It is predicated on the idea that broadband is a limited resource that must be carefully managed and, in some cases, metered. Companies like Cox and Comcast now usage-cap their customers and deter them from exceeding their allowance with overlimit penalties. AT&T subjectively usage caps their customers as well, but strictly enforces caps only for its legacy DSL customers. Charter Communications sells Spectrum customers on the idea of a one-size fits all, faster broadband option, but then strongly repels those looking to upgrade to even faster speeds with an indefensible $200 upgrade fee.

Rationing Your Internet Experience?

“The fixation with video means the telecom industry is concentrating too much on limiting user traffic,” Odlyzko writes. “In many ways, the danger for the industry, especially in the wireline arena, is from too little traffic, not too much. The many debates as to whether users really need 100Mbps connections, much less 1Gbps ones, reveal lack of appreciation that burst capability is the main function of modern telecom, serving human impatience. Although pre-recorded video dominates in the volume of traffic, the future of the Net is likely to be bursts of traffic coming from cascades of interactions between computers reacting to human demands.”

Burstein agrees.

“The problem for most large carriers is that they can’t sell the capacity they have, not that they can’t keep up,” he writes. “The current surge in 5G millimeter wave [talk] is not because the technology will be required to meet demand. Rather, it is inspired by costs coming down so fast the 5G networks will be a cheaper way to deliver the bits. In addition, Verizon sees a large opportunity to replace cable and other landlines.”

On the subject of cost and broadband economics, Burstein sees almost nothing to justify broadband rate hikes or traffic management measures like usage caps or speed throttling.

“Bandwidth cost per month per subscriber will continue flat to down,” Burstein notes. “For large carriers, that’s been about $1/month [per customer] since ~2003. Moore’s Law has been reducing equipment costs at a similar rate.”

“Cisco notes people are watching more TV over the net in evening prime time, so demand in those hours is going up somewhat faster than the daily average,” he adds. “This could be costly – networks have to be sized for highest demand – but is somewhat offset by the growth of content delivery networks (CDN), like Akamai and Netflix. (Google, YouTube, and increasingly Microsoft and Facebook have built their own.) CDNs eliminate the carrier cost of transit and backhaul. They deliver the bits to the appropriate segment of the carrier network, reducing network costs.”

Both experts agree there is no evidence of any internet traffic jams and routine upgrades as a normal course of doing business remain appropriate, and do not justify some of the price and policy changes wired and wireless providers are seeking.

Both experts agree there is no evidence of any internet traffic jams and routine upgrades as a normal course of doing business remain appropriate, and do not justify some of the price and policy changes wired and wireless providers are seeking.

But Wall Street doesn’t agree and analysts like New Street Research’s Jonathan Chaplin believe broadband prices should rise because with a lack of competition, nothing stops cable companies from collecting more money from subscribers. He isn’t concerned with network traffic growth, just revenue growth.

“As the primary source of value to households shifts increasingly from pay-TV to broadband, we would expect the cable companies to reflect more of the annual rate increases they push through on their bundles to be reflected in broadband than in the past,” Chaplin wrote investors. Comcast apparently was listening, because Chaplin noticed it priced standalone broadband at a premium $85 for its flagship product, which is $20 more than Comcast’s non-promotional rate for customers choosing a TV-internet bundle.

“Our analysis suggests that broadband as a product is underpriced,” Chaplin wrote. “Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing. The companies will undoubtedly have to take pay-TV pricing down to help ‘fund’ the price increase for broadband, but this is a good thing for the business. Post re-pricing, [online video] competition would cease to be a threat and the companies would grow revenue and free cash flow at a far faster rate than they would otherwise.”

Subscribe

Subscribe

With the advent of AT&T/DirecTV Now, AT&T’s new over-the-top streaming TV service launching later this year, AT&T

With the advent of AT&T/DirecTV Now, AT&T’s new over-the-top streaming TV service launching later this year, AT&T

Just like its wireless service, AT&T stands to make money not just selling access to broadband and entertainment, but also by metering customer usage to monetize all aspects of how customers communicate. Getting customers used to the idea of having their consumption measured and billed could gradually eliminate the expectation of flat rate service, at which point customers can be manipulated to spend even more to access the same services that cost providers an all-time low to deliver. Even zero rating helps drive a belief the provider is doing the customer a favor waiving data charges for certain content, delivering a value perception made possible by that provider first overcharging for data and then giving the customer “a break.”

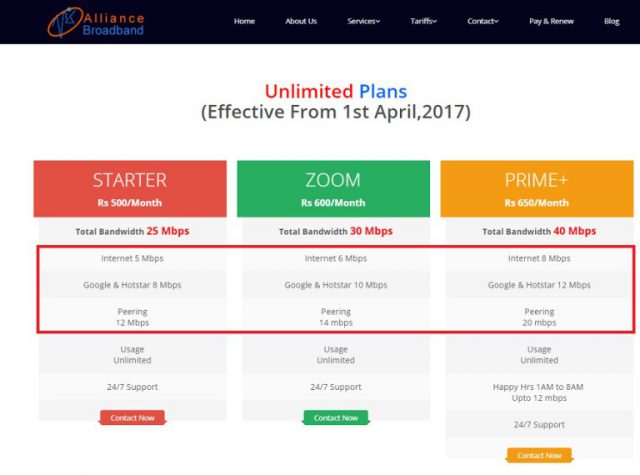

Just like its wireless service, AT&T stands to make money not just selling access to broadband and entertainment, but also by metering customer usage to monetize all aspects of how customers communicate. Getting customers used to the idea of having their consumption measured and billed could gradually eliminate the expectation of flat rate service, at which point customers can be manipulated to spend even more to access the same services that cost providers an all-time low to deliver. Even zero rating helps drive a belief the provider is doing the customer a favor waiving data charges for certain content, delivering a value perception made possible by that provider first overcharging for data and then giving the customer “a break.” How much you use the Internet is often a matter of how fast your broadband connection is, according to a new study.

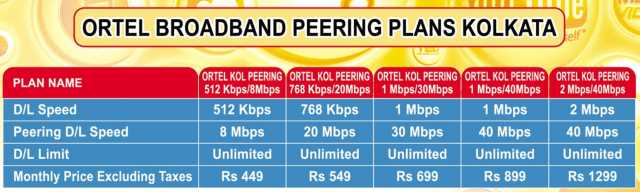

How much you use the Internet is often a matter of how fast your broadband connection is, according to a new study.