Bell is pulling out all the stops trying to defend its justification for Internet Overcharging through so-called usage-based billing. In a published debate between the telecom giant and TekSavvy — a small independent ISP trying to preserve flat rate broadband service in Canada, Bell claims Canadian broadband is the third best in the world, ahead of the United States, all of Europe, and just barely trailing Japan and Korea:

Bell is pulling out all the stops trying to defend its justification for Internet Overcharging through so-called usage-based billing. In a published debate between the telecom giant and TekSavvy — a small independent ISP trying to preserve flat rate broadband service in Canada, Bell claims Canadian broadband is the third best in the world, ahead of the United States, all of Europe, and just barely trailing Japan and Korea:

At the same time, Canada has increasingly become a world leader when it comes to broadband. When it comes to actual download speeds, Canada ranks third in the G20, behind only densely populated Korea and Japan. And prices are low — in fact, for higher-speed services, lower than in both the U.S. and Japan.

Michael Geist, a popular columnist fighting against Canadian Internet Overcharging, scoffs at the notion:

I’m not sure where these claims come from – Canada does not appear in the top 10 on Akamai’s latest State of the Internet report for Internet speed and no Canadian city makes Akamai’s top 100 for peak speed. The OECD report ranks Canada well back in terms of speed and price as does the Berkman report. The NetIndex report ranks Canada 36th in the world for residential speed. Moreover, the shift away from the OECD to the G20 has the effect of excluding many developed countries with faster and cheaper broadband than Canada (while bringing in large, developing world economies that unsurprisingly rank below Canada on these issues). While there is probably a report somewhere that validates the claim, the consensus is that Canada is not a leader.

Bell’s Magic Pony-stories are at best exaggerated and at worst, phoney-baloney from the telco’s government relations department.

Stop the Cap! compared prices across several providers and found no value for money in broadband plans from all of the country’s major phone and cable companies. Without fail, all were heavily usage limited, most throttled broadband speeds for peer-to-peer applications, engaged in overlimit fees the credit card industry would be proud to charge, and simply were almost always behind their counterparts to the south — in the United States. In fact, some consumers are importing their broadband from the USA when they can manage it.

“Bell can’t win the argument on the merits, so it is making things up,” writes London, Ontario resident Hugh MacDonald. “I have had Bell DSL for years now, and there isn’t anything fast or cheap about it.”

MacDonald’s broadband service from Bell tops out at around 4Mbps.

Mirko Bibic, senior vice-president for regulatory and government affairs at Bell claims consumers have to pay more to fund infrastructure expansion, and even challenges our long-standing assertion that telephone network comparisons don’t apply:

Bell provides all our customers with the best possible Internet experience available — the result of heavy and ongoing investment to expand our network capacity both to meet fast-growing demand and to manage the congestion that threatens everyone’s Internet experience.

Internet congestion is a fact and it cannot be wished away. Network providers like Bell must, like hydro utilities, build our networks to handle the heaviest usage times, not just an average of usage over time. At 8:30 in the evening, demand is at its absolute peak. And we have to deliver based on the volume at that time.

Keeping up with growing volume obviously means these network investments are not one-time costs. Between 2006 and 2009, Internet usage more than doubled, and Bell has invested more than $8-billion in the last five years in network growth and enhancement to keep pace. Yet at the same time, the CRTC has found that the average price per gigabyte downloaded has actually declined by 20%.

That’s why the long distance analogy, so often used by those with an interest in confusing the issue, is fundamentally misleading. In the case of long distance, it’s the simple transmission of voice over long-established legacy networks.

But Bibic ignores several important facts and doesn’t disclose others:

But Bibic ignores several important facts and doesn’t disclose others:

What broadband network does not have to make regular investments to expand to meet demand? Cable and telephone company DSL business models, in place for at least a decade, priced network expansion, infrastructure return on investment, and data transmission into pricing formulas. While data demands are increasing, the costs to meet those demands are, as Bell openly admits, declining.

What amount of revenue and profit has been earned from selling broadband service to Canadian consumers and the wholesale market and how does that compare to the dollar amount invested? Bell Canada’s financial report for the third quarter of 2010 shows the company will earn an estimated $3.5 billion in revenue from its broadband Internet division alone. Bell’s capital spending numbers also include network investments for its fiber to the neighborhood service, Fibe. Bell’s revenue from selling the video side of that service were on track to deliver an additional $1.5 billion in revenue in 2010. Not including the enormous wholesale broadband market, Bell will earn at least $5 billion a year from its broadband division.

In fact, Bell’s financial report also openly admits much of its capital spending increases have been spent on deploying its IPTV network Fibe in Ontario and Quebec, not on Internet backbone traffic management.

What are some of Bell’s biggest risks to a happy-clappy shareholder report for investors next quarter? To quote:

- “Our ability to implement our strategies and plans in order to produce the expected benefits;

- Our ability to continue to implement our cost reduction initiatives and contain capital intensity;

- The potential adverse effects on our Internet and wireless businesses of the significant increase in broadband demand;

- Our ability to discontinue certain traditional services as necessary to improve capital and operating efficiencies;

- Regulatory initiatives or proceedings, litigation and changes in laws or regulations.”

Bibic

As for Bell’s claims about the “long distance analogy,” it’s only slightly ironic that a telecommunications company considers today’s voice networks radically different from data networks. Analog transmission of voice calls went the way of the telegraph around a decade ago, with the last analog, step-by-step telephone switch in North America in Nantes, Quebec switched off in late 2001. Today, telephone traffic is digital data, no different than any other kind of data transported across the country.

Bell cannot afford to have comparisons made between the telephone company’s move towards flat rate billing for phone calls and their broadband service moving away from it, because it torpedoes their entire argument.

Bibic then argues UBB is the right way to go because… major providers already charge it:

UBB has been the established framework for Internet services in Canada for years. Bell, for example, offers standard Internet service packages ranging from 25 gigabytes up to 75 gigabytes per month. As well, customers can sign up for 40 GB more for $5 per month, 80 GB for $10 or a whopping 120 GB more for $15. Keep in mind that 120 GB will get you 600 hours of standard definition video streaming or 100 hours of HD video streaming.

Not a bad deal when you consider average usage on our network is 16 GB per month and half of our customer base uses just five GB a month.

Most Canadians don’t see the “good deal” Bell says they will get from dramatically increased broadband prices. In fact, polls reveal the only groups in Canada that support such pricing are Big Telecom executives and the CRTC.

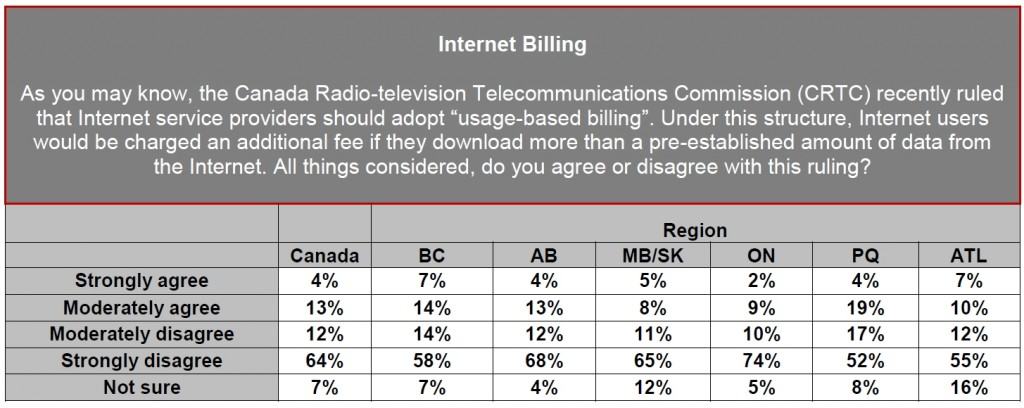

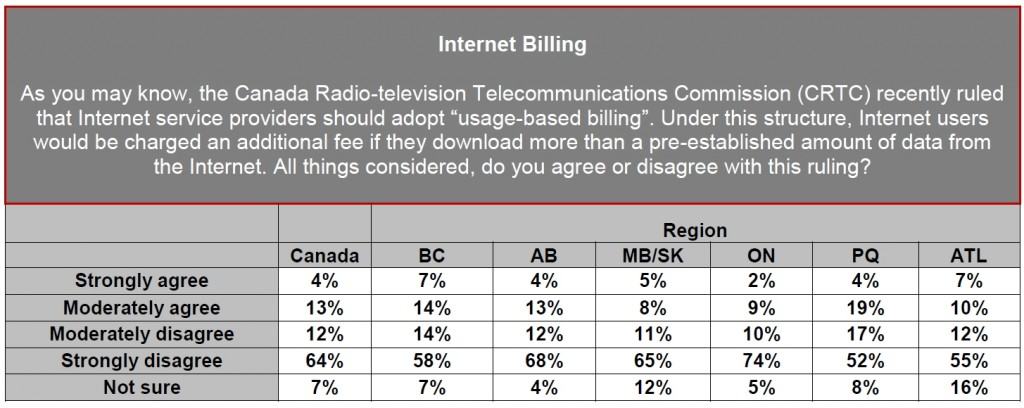

A new Angus Reid/Toronto Star poll illustrates what we’ve found to be true wherever ripoff “usage-based” pricing appears: people despise it, no matter how much Internet they use:

In the online survey of a representative national sample of 1,024 Canadian adults, three-in-four respondents (76%) disagree with the recent decision from the Canada Radio-television Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which set the stage to eliminate unlimited use plans.

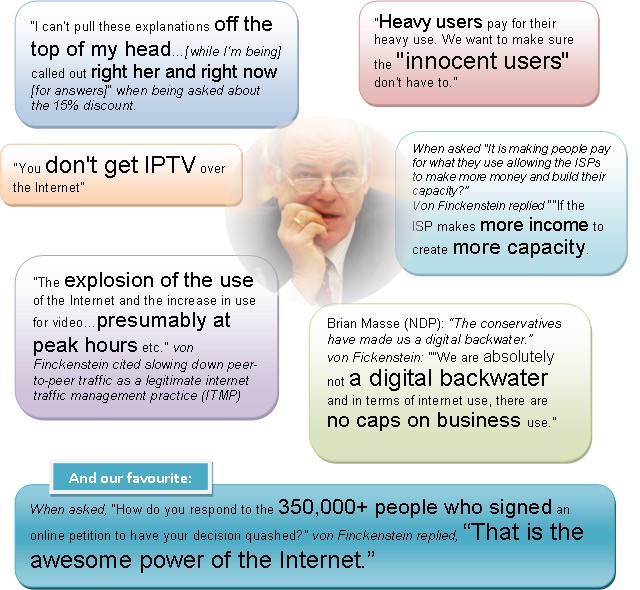

Bibic can relax as long as the current panel of commissioners at the CRTC, largely drawn from telecommunications companies, remain in place. They continue to agree with Bell’s point of view and ignore the citizens they are supposed to represent.

CBC Radio One: The Current explores Internet Overcharging in Canada:

CBC Radio One: The Current explores Internet Overcharging in Canada: It’s hard to believe that just eighteen years ago — back in 1993 — we were only beginning to grasp what the Internet could do for us. Today, the Internet is an integral part of the global economy, a powerful political tool, and something many couldn’t imagine living without. That’s partly why the cost of Internet access has been at the centre of a national debate for the past week.

It’s hard to believe that just eighteen years ago — back in 1993 — we were only beginning to grasp what the Internet could do for us. Today, the Internet is an integral part of the global economy, a powerful political tool, and something many couldn’t imagine living without. That’s partly why the cost of Internet access has been at the centre of a national debate for the past week.

Subscribe

Subscribe