AT&T's Fairy Tales of Broadband Congestion

Just a few days after Broadband Reports broke the news AT&T was imposing an Internet Overcharging scheme on its broadband customers, evidence continues to arrive illustrating the company’s planned usage limits are more about protecting their U-verse video business than actually controlling “heavy users.”

Dave Burstein, a well-known industry analyst who has tracked the broadband universe for years was so miffed about the nonsense he was reading in the Wall Street Journal, he picked up the phone and called the AT&T spokesperson who claimed the company was overburdened by heavy users:

Mark Siegal, AT&T’s top flack, hung up the phone on me when I said his comment to the Wall Street Journal was apparently a lie. It’s prohibitively unlikely their DSL cap “is to ensure the quality of the customer experience” necessary to solve “congestion in certain points of the network and interfering with other people’s access.” I’m certain that far less than 1% of the time do AT&T DSL customers have any impact from congestion. I’m pretty confident it’s less than 1/10th of 1% and probably less than 1/100th of 1%. My sources that wireline congestion on AT&T is minimal include statements from two CTOs of the company. Cheng, now a veteran in D.C., knew the comment was misleading at best. A mantra in D.C. is “wireline may not have congestion but wireless is different.” It was Sunday and perhaps hard to factcheck, but he’ll easily confirm the problem on Monday.

AT&T has long maintained they have a more robust network and cable is the one with “bandwidth hog” problems. But Comcast’s cap was 60% higher than AT&T and Comcast has said they will raise it. AT&T has gone 13 years without caps on their DSL network because they said they didn’t need them. Traffic growth is actually down slightly (Cisco, Odlyzko) so there’s only one reason to impose caps now: their video service, U-Verse, has become a $5B business. They don’t want people to be able to cut the cord and watch all their video over the net. 150 gigabytes is 40-80 hours of U-Verse quality TV, far less than the average U-Verse user watches.

In fact, AT&T is one of America’s largest Internet Service Providers, and maintains an important role in America’s Internet backbone. As one of the largest providers, AT&T doesn’t worry about broadband traffic like a small wireless ISP does. Its broadband pipes from the middle-mile to their nationwide network offers near limitless capacity thanks to fiber optic technology. In fact, AT&T’s theoretical “bottlenecks” occur in the “last mile” of the network, from the phone company’s central switching offices or its interface between a fiber connection and the plain old copper wires that work their way into your home or business.

But first, a word about costs.

Dave Burstein

We have new evidence from both Burstein and the Internet Overcharging drama unfolding in Canada that providers literally pay pennies per gigabyte of traffic. In fact, the broadband traffic customers generate represents only 2%-5% of what we pay for broadband in both countries. Burstein uses some of Craig Moffett’s prolific comments in the media against his own argument for Internet Overcharging. Moffett, a Wall Street analyst, is not alone when he reports broadband margins are as high as 90%, according to official company filings. John Hodulik from UBS joins him.

Burstein gives providers’ argued need for increased investment to keep up with demand the benefit of the doubt and is willing to suggest profit margins at a reduced 75%. In either case, running a large broadband network is a veritable license to print money in North America. The costs to provide the service keep dropping, and providers keep on raising prices.

Burstein was generous with Comcast when he called their 250GB usage limit imposed in 2008 “fair.” But as Stop the Cap! has argued, Comcast — like other Internet Overchargers — has not grown the cap over time, even as their costs decline. In fact, customers are probably lucky the country’s largest cable operator hasn’t reduced it, as providers in Canada have done repeatedly. Burstein calls on Comcast to honor their promise and raise their cap.

Burstein also notes the rest of the world enjoys lower prices, more competition, and often faster service — with providers across the board still enjoying considerable profits.

But why not here?

America’s broadband market is a monopoly or duopoly in virtually every American city. One cable operator and one telephone company deliver service to the vast majority of American broadband users. Wireless providers are largely owned by legacy phone companies and strictly limit usage. Without significant competition, providers can raise prices at will and milk profits to sustain their balance sheets even as other business divisions suffer from a downturned economy or shifting cultural changes. The “landline” is rapidly becoming a thing of the past, and cable television provided by cable and phone companies could face cord cutting from consumers watching their favorite shows over their broadband connections.

Broadband service carries up to a 90 percent profit margin

Burstein tracks the business model:

15 gigabytes/month: The average (mean) user in the U.S., per Cisco’s respected VNI survey and numerous comments from the major companies.

Going Down: Bandwidth usage growth per customer. The rate has been about 30% per year, with the rate slightly falling the last few years. The growth in average usage is actually going down slightly, per Cisco VNI and the MINTS data of Professor Andrew Odlyzko.

Going Down: Capital investment required. In 2009, AT&T cut U-Verse by 1/3rd. In 2010, Verizon cut FiOS by 2/3rds. John Stankey of AT&T has said they will cut U-Verse much further after this year. Fran Shammo of Verizon says “Wireline will continue to come down year over year.” Cablecos have been dropping capex as a % of sales and often in absolute dollars. According to a recent survey by Heavy Reading, 70% of the cable networks have been upgraded to DOCSIS 3.0 already. There’s no significant capital spending beyond that at least until mid-decade. The Columbia University CITI report to the broadband plan aggregated analysts forecast and predicted a drop in overall capital spending on broadband, particularly in wireline. The primary capital spending for wired broadband is behind us, with few significant network buildouts in the next five years or longer.

Going Up: Profit Margins. Prices for broadband have generally been going up in the U.S. since 2007 while costs drop. Comcast, Time Warner, Verizon and most others have raised their broadband prices and ARPU. They also have (modestly) raised the prices of triple play including broadband, according to Dave Barden of Bank of America. Capex is dropping pretty dramatically while other operating costs are also falling. Customer support costs have gone down as few new customers (who need more support) are added. Modems and other gear continue dropping in price. Costs down, prices up = higher profits. Both Stankey and Shammo pointed to improved margins.

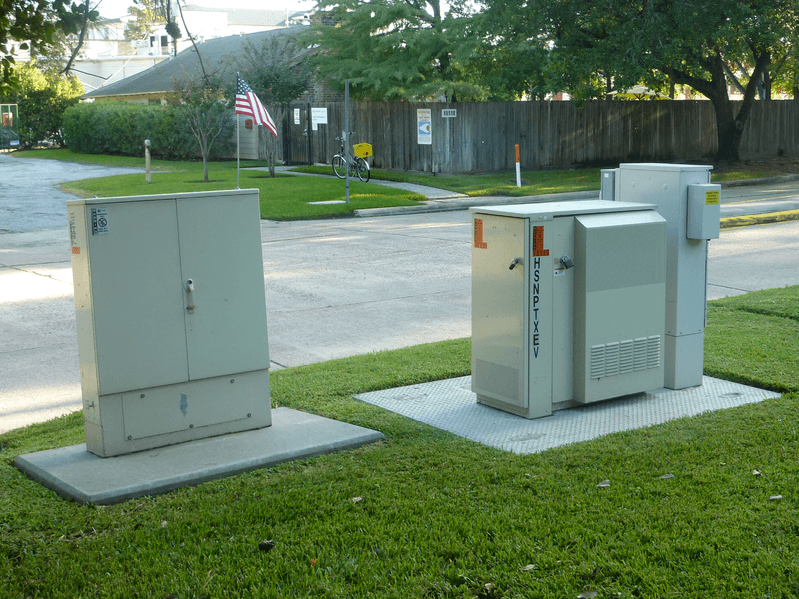

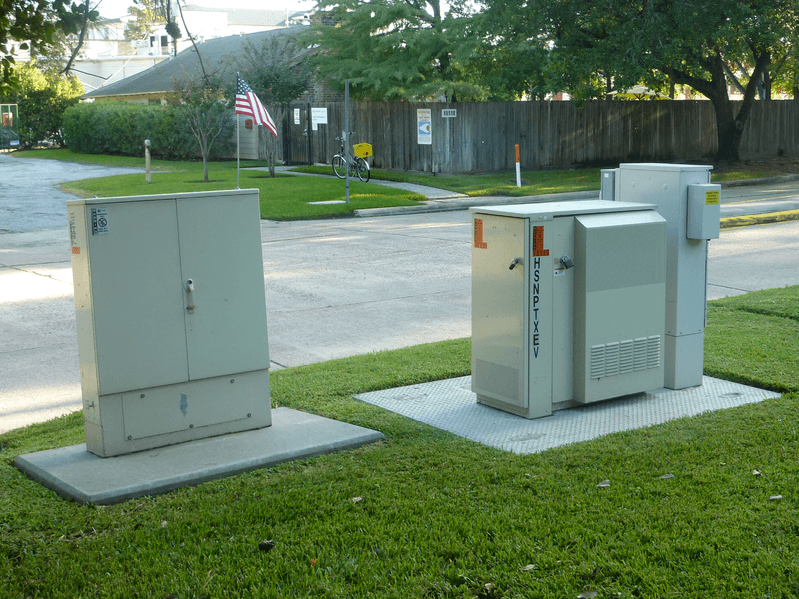

AT&T DSL (left) vs. AT&T U-verse (right): Hunting season on customers of both is now open.

AT&T argues their usage caps are less about the money and more about dealing with network congestion. But does that play out?

AT&T has a convenient argument to use, which several journalists have come to believe gives the company a track record of being victimized by “heavy users.” Namely, their network congestion brought about by the flood of iPhone users on AT&T Mobility’s cellular network. Even if a reporter does not understand the profound differences between a wired and wireless broadband network, they have heard about AT&T’s problems coping with their wireless traffic.

In short, the company underestimated demand from its exclusive deal with Apple for the wildly popular phone, and refused to invest adequately to mitigate overcongested cities. Instead, it spent millions lobbying for permission to “manage” the traffic with artificially-slowed speeds, usage limits, confiscatory overlimit penalties, and even some equipment to offload wireless users onto home broadband connections (for which AT&T still deducts airtime and data usage from your wireless allowance.) Robust Wi-Fi also tries to drive customers off of AT&T’s inadequate 3G network.

For home broadband users who will be affected by AT&T’s Internet Overcharging scheme, let’s break them into two separate categories: DSL customers who face a 150GB cap and U-verse customers who will get a 250GB allowance.

AT&T DSL is a legacy product dependent on traditional copper wire phone lines. Available in many areas unserved by U-verse, this technology typically provides up to 6Mbps service — often slower, sometimes higher. The distance between the phone company office and one’s home usually determines what speeds customers receive. In rural areas, 1-3Mbps is often typical. In some urban areas, higher speeds are sometimes possible. DSL is not a “shared” technology like cable broadband. Each DSL customer has their own line between their home and central office (or remote repeater). From there, a connection from the central office to AT&T’s backbone is made over a middle mile network.

AT&T U-verse VRADs (a/k/a 'lawn refrigerators') in Houston, Tex. (Courtesy: Swapdisk)

But AT&T’s DSL customers are already constrained by the reduced speeds DSL provides them. It is unlikely a customer with 3Mbps DSL service is going to present much of a traffic challenge to a multi-billion dollar company unless they purposely under-invest in network upgrades.

Where congestion does exist, it occurs at the central office — usually because the company inadequately provisioned a sufficiently large data pipe to handle the traffic. Since these circuits are increasingly fiber-based, congestion issues disappear when AT&T uses technology from this century instead of the last.

AT&T argues heavy users are overburdening their DSL lines, but their prescription makes no sense. The company says, despite the alleged traffic jam, it is more than willing to sell users additional capacity for $10 per 50GB increment. If AT&T’s aim was to cut congestion, they would be unwilling to sell additional capacity they don’t have to customers who need it.

A usage cap on AT&T’s new U-verse platform makes even less sense and opens a political minefield.

When one pushes away the promotional and marketing glitz AT&T provides when pitching U-verse, you are left looking at just one thing — a high speed broadband connection. AT&T’s entire platform of television, phone, and broadband all resides on that single, super-speed broadband pipeline.

AT&T has built this super fast pipe with a combination of fiber optic cables and copper phone wires. It uses fiber, which doesn’t degrade with distance the way copper wire connections do, to reduce the amount of copper phone wiring between your home and AT&T. With this “fiber to the neighborhood” approach, AT&T can create a robust pipeline which can accommodate multiple television channels, a phone line, and your broadband connection all running concurrently.

AT&T only seeks to limit one part of that connection, however: the broadband service you could theoretically use to bypass AT&T’s television and phone service in favor of another provider. It’s the same platform — only the services are different.

AT&T claims network congestion is a problem for U-verse as well, which is a controversial claim to make considering AT&T designed U-verse with excess capacity that goes unused to this day.

What does AT&T’s U-verse network look like?

AT&T’s regional offices maintain watch over their U-verse network of TV, Internet, and phone services. This portion of the network is entirely fiber-based. From there, fiber extends to individual central offices, part of the company’s middle-mile network. AT&T’s fiber journey typically ends at large metal cabinets strategically placed in different neighborhoods. These “Video Ready Access Devices” (VRADs) are probably familiar to you if you live in an AT&T area. Sometimes derided as “lawn refrigerators,” the huge metal cabinets contain the interface between the fiber optic network and the copper wire telephone lines running to your home.

It’s this “choke point” AT&T tries to claim as a point of congestion. If enough customers use their connection at the same time, it can “overburden” the network. But can it, really?

Early adopters of U-verse pestered AT&T engineers about the network as it was constructed and learned a lot about it.

Phil Karn has been a U-verse customer since November 2009 and has become an expert on how his U-verse service works, and importantly how it holds back a considerable amount of available bandwidth.

An AT&T engineer “tried to tell me that the network equipment was like the engine in a sports car. You don’t want to drive it at the red line all the time because that will wear it out. I don’t know if he was told to use that analogy or if he came up with it on his own, but needless to say it’s a pretty silly one. And completely inapplicable,” Karn shares on his website.

He then claimed, rather weakly, that backhaul capacity considerations from the VRAD limit how much can be offered to each individual subscriber. This argument might even have begun to hold water except for the numbers he then provided. The VRADs, he said, are connected by 10 gigabit Ethernet over fiber, and each VRAD serves upwards of 200 homes. Let’s see…10 gigabits over 200 homes is 50 megabits per home. My [U-Verse] link runs at 32.2Mbps.

The whole point is that it doesn’t really matter how fast or slow the backhaul from the VRAD may be. With modern Internet routers and priority [Quality of Service] mechanisms, there is no reason to force capacity to remain idle when a user could be using it. Not unless, of course, you’re trying to maintain the public impression that broadband capacity is really scarce and expensive.

Karn

In fact, because few Internet users fully drive their broadband connections on a continuous basis, it can be argued that continuous video streams delivered to television sets left on in the homes of U-verse customers for hours at a time present a bigger “congestion” problem for AT&T, at least at this point in their network. But the company has no plans to limit television viewing — only their broadband Internet service.

U-verse is AT&T’s answer to slow speed DSL, and part of how the company intends to stay relevant as landline customers depart. But the company’s business plan depends on a certain percentage of customers subscribing to their pricey television service. Should AT&T’s broadband customers decide to stop paying for television service, watching everything online instead, that threatens a $5 billion dollar business.

Burstein predicted this scenario when he discussed it with former FCC Chairman Kevin Martin:

“In 2005, Kevin Martin discussed with me the issue of what he would do if AT&T favored U-verse. I believe he felt he would have to act, but at that point hoped competition would prevent him from facing that decision. Now AT&T’s multi-million dollar über-lobbyist Jim Cicconi has presumably told them [current FCC Chairman] Julius Genachowski is sufficiently under control he won’t do anything about this.”

In the end, many of AT&T’s arguments simply are incoherent. If only a small handful of AT&T customers are creating such a dilemma for the company it has to inconvenience every customer with a usage limit, AT&T has a much larger problem to contend with. Furthermore, the company’s existing acceptable use policy already includes provisions for dealing with users that create problems on their network, all without bothering everyone else.

Subscribe

Subscribe