Comcast has changed its explanation why the company’s XFINITY TV service, streamed over Xbox 360 has been made exempt from the company’s 250GB usage cap.

Comcast has changed its explanation why the company’s XFINITY TV service, streamed over Xbox 360 has been made exempt from the company’s 250GB usage cap.

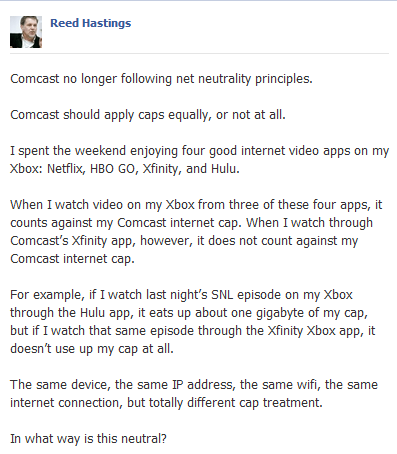

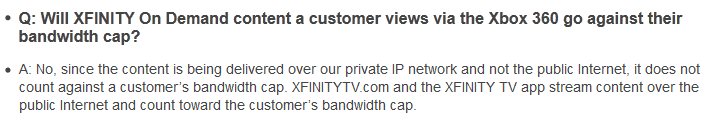

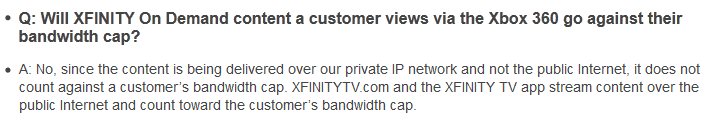

Last week, the company claimed the service traveled over the company’s “private IP” network, exempting it from usage restrictions. That created a small furor among public interest groups and Net Neutrality supporters because of the apparent discrimination against streamed video content not partnered with the country’s biggest cable operator.

Stop the Cap! argued what we’ve always argued — usage caps and speed throttles are simply an end run around Net Neutrality — getting one-up on your competition without appearing to openly discriminate.

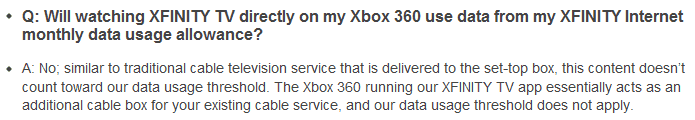

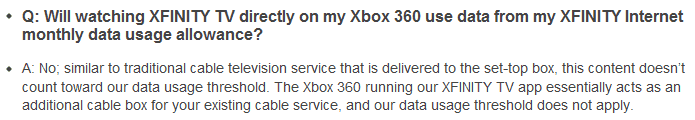

Now Comcast hopes to make its own end run around the topic by changing the language in its FAQ:

Before:

After:

Although the words have changed, the story stays the same.

The key principle to remember:

Data = Data

Comcast suggests its Xbox XFINITY TV service turns your game console into a set top box, receiving the same type of video stream its conventional cable boxes receive. The cable company is attempting to conflate traditional video one would watch from an on-demand movie channel as equivalent to XFINITY TV over the Xbox. Since the video is stored on Comcast’s own IP network, the company originally argued, it creates less of a strain on Comcast’s cable system.

AT&T's U-verse is an example of an IP-based distribution network.

But the cable industry’s inevitable march to IP-based delivery of all of their content may also bring a convenient excuse to proclaim that data does not always equal data. They have the phone companies to thank for it.

Take AT&T’s U-verse or Bell’s Fibe. Both use a more advanced form of DSL to deliver a single digital data pipeline to their respective customers. Although both companies try to make these “advanced networks” sound sexy, in fact they are both just dumb data pipes, divided into segments to support different services. The largest segment of that pipe is reserved for video cable TV channels, which take up the most bandwidth. A smaller slice is reserved for broadband, and a much smaller segment is set aside for telephone service.

AT&T and Bell’s pipes don’t know the difference between video, audio, or web content because they are all digital data delivered to customers on an IP-based network. Yet both AT&T and Bell only slap usage caps on their broadband service, claiming it somehow eases congestion, even though video content always uses the most bandwidth. (They have not yet figured out a way to limit your television viewing to “maintain a good experience for all of their customers,” but we wouldn’t put it past them to try one day.)

What last mile congestion problem?

Comcast’s argument for usage limiting one type of data while exempting other data falls into the same logical black hole. Comcast’s basic argument for usage caps has always been it protects a shared network experience for customers. Since cable broadband resources are shared within a neighborhood, the company argues, it must impose limits on “heavy users” who might slow down service for others.

We've heard this all before. Former AT&T CEO Dan Somers: "AT&T didn’t spend $56 billion to get into the cable business to have the blood sucked out of (its) veins."

But in a world where DOCSIS 3 technology and a march to digital video distribution is well underway or near completion at many of the nation’s cable operators, the “last mile” bandwidth shortage problem of the early 2000s has largely disappeared. In fact, Comcast itself recognized that, throwing the usage door wide open distributing bandwidth heavy XFINITY TV over the Xbox console cap-free.

As broadband advocates and industry insiders continue the debate about whether this constitutes a Net Neutrality violation or not, a greater truth should be considered. Stop the Cap! believes providers have more than one way to exercise their control over broadband.

Naked discrimination against web content from the competition is a messy, ham-handed way to deal with pesky competitors. Putting up a content wall around Netflix or Amazon is a concept easy to grasp (and get upset about), even by those who may not understand all of the issues.

Internet Overcharging schemes like usage caps and speed throttles can win providers the same level of control without the political backlash. Careful modification of consumer behavior can draw customers to company-owned or partnered content without using a heavy hammer.

Simply slap a usage limit on customers, but exempt partnered content from the limit. Now customers have a choice: use up their precious usage allowance with Netflix or watch some of the same content on the cable company’s own unlimited-use service.

Nobody is “blocking” Netflix, but the end result will likely be the same:

- Comcast wins all the advantages for itself and its “preferred partners”;

- Customers find themselves avoiding the competition to save their usage allowance;

- Competitors struggle selling to consumers squeezed by inflexible usage caps.

It is all a matter of control, and that is nothing new for large telecom companies.

Back in 1999, AT&T Broadband owned a substantial amount of what is today Comcast Cable. Then-CEO Dan Somers made it clear AT&T’s investment would be protected.

“AT&T didn’t spend $56 billion to get into the cable business to have the blood sucked out of [its] veins,” Somers said, referring to streamed video.

Obviously Comcast agrees.

Subscribe

Subscribe