Nearly 10 percent of GCI’s revenue is now earned from overlimit fees collected from Alaskan broadband customers who exceed their cable or wireless usage limits.

Nearly 10 percent of GCI’s revenue is now earned from overlimit fees collected from Alaskan broadband customers who exceed their cable or wireless usage limits.

GCI is Alaska’s largest cable operator and for many it is the only provider able to deliver stable speeds of 10Mbps+, especially to those who live too far away for comparable DSL speeds from ACS, one of GCI’s largest competitors.

The result has given GCI a de facto monopoly on High Speed Internet (10+ Mbps) access, a position that has allowed the company to dramatically raise prices and slap usage limits on broadband users and charge onerous overlimit fees on those who exceed their allowance.

GCI already charges some of the highest broadband service prices in the country and has insisted on imposing usage caps and overlimit fees on even its most expensive plans, creating high profits for them and enormous bills for customers who have no reliable way to consistently track their usage. GCI’s suspect usage meter is often offline and often delivers usage estimates that customers insist are far from accurate. GCI says it has the last word on the accuracy of that meter and has not submitted its meter to independent testing and verification by a local or state regulatory body specializing in measurement accuracy.

GCI also makes it extremely difficult for customers to understand what happens after customers exceed their usage limits. The website only vaguely offers that overlimit fees vary from “$.001 (half penny) to $.03 (three cents) per MB,” which is factually inaccurate: $.001 does not equal a half-penny. It can equal bill shock if a customer happens to be watching a Netflix movie when their allowance runs out.

KC D’Onfro of Bethel subscribes to GCI’s Alaska Extreme Internet plan, which in February cost $100 a month for 4/1Mbps service with a 25GB usage cap. While that allowance is plenty for the countless e-mails GCI promises you can send, any sort of streaming video can chew through that allowance quickly.

Business Insider explains what happened:

One fateful night, she and her roommate decided to watch a movie on Netflix. Both of them fell asleep halfway through, but the movie played ’til the end, eating up two GBs of data too many and consequently doubling their bill for that month. (One hour of HD video on Netflix can use up to 2.3 GB of data.)

“Now, I don’t even consider Netflix until near the very end of the month, and I have to be sure that I’m no more than three-fourths of the way into my total data, at the absolute most,” KC says. (Her provider, a company called GCI, allows subscribers to view their daily usage and sends them a notice when they’ve hit 80%.) “It’s a very serious business – I have to poll people to figure out what that one very special movie should be.”

That left the D’Onfro family with a $200 broadband bill – $100 for the service and an extra $100 overlimit fee for that single Netflix movie. Today, GCI demands $114.99 a month for that same plan (with the same usage allowance) and those not subscribing to their TV service also face a monthly $11.99 “access fee” surcharge for Internet-only service.

“Many Alaska consumers have brought their GCI broadband bills to ACS for a comparative quote, providing dozens of examples of GCI overage charges,” said Caitlin McDiffett, product manager of Alaska Communications Systems (ACS), the state’s largest landline phone company. “Many of these examples include overage charges of $200 to $600 in a single month. In one instance, a customer was charged $1 ,200 in overage fees.”

GCI also keeps most customers in place with a 24-month contract, making it difficult and costly to switch providers.

McDiffett told the FCC the average Alaskan with a Netflix subscription must pay for at least a 12Mbps connection to get the 60GB usage allowance they will need to watch more than two Netflix movies a week in addition to other typical online activities. GCI makes sure that costs average Alaskans real money.

“A customer purchasing 12Mbps for standalone (non-bundled) Home Internet from GCI pays $59.99 per month plus an $11.99 monthly “access” fee for a total of $71.98 per month with a 60GB usage limit ($0.004/MB overage charge),” reports McDiffett. “Thus, the monthly bill for this service is more typically $76.98, including a $5.00 overage charge. To purchase a service with a usage limit of at least 100GB per month, a GCI customer would have to pay $81.98 per month (the $69.99 standalone rate plus $11.99 monthly access fee), subject to an overage charge of $0.003/MB.”

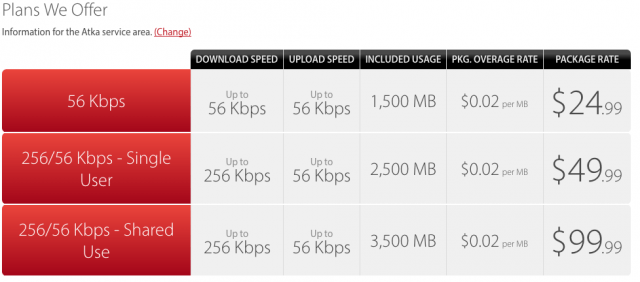

Rural Alaskans pay even more when using GCI’s expensive wireless ISP.

Regular Alaskan Stop the Cap! reader Scott reports that no matter what plan you choose from GCI, they are waiting and ready to slap overlimit fees on you as soon as they decide you are over your limit.

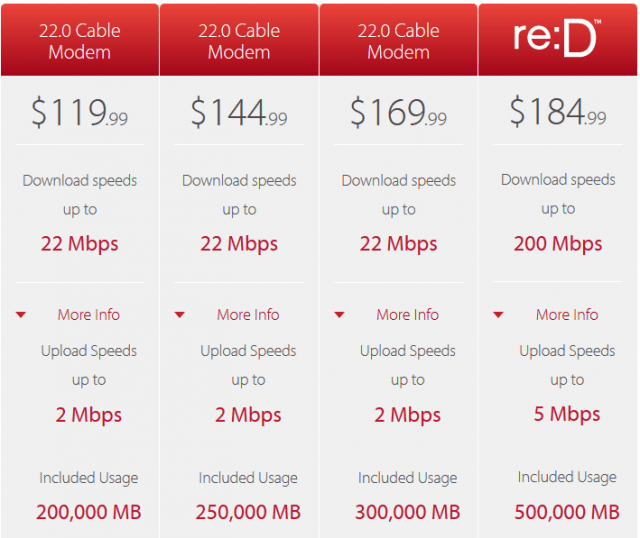

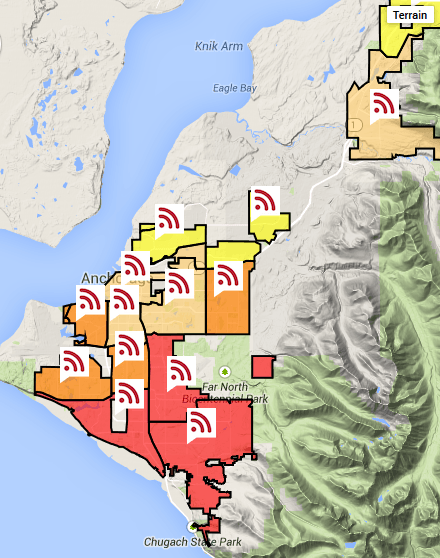

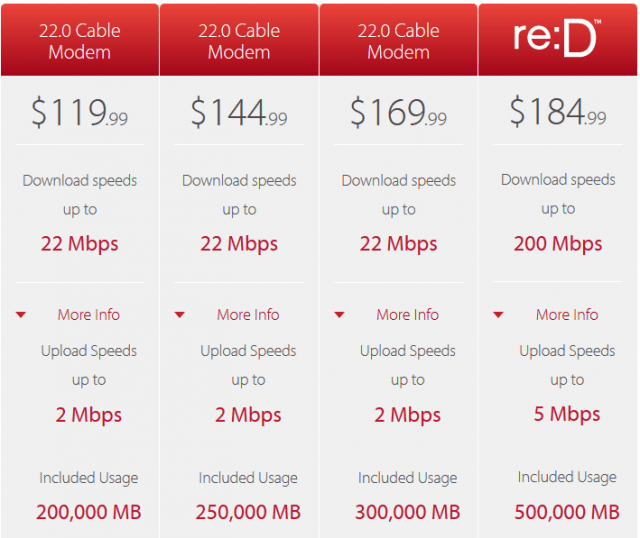

Their super-deluxe re:D service — up to 200Mbps, now available in Anchorage, MatSu, Fairbanks, Juneau, Kenai, Ketchikan, Sitka, and Soldotna areas, is not cheap.

“It’s a whopping $209.99 + taxes, and if you don’t have cable TV service bundled, the $11.99 monthly access fee also applies,” Scott says.

For that kind of money, one might expect a respite from the usage meter, but not with GCI.

“As a top tier service, you’d think they could just offer it as ’unlimited’ at that rate,” Scott says. “Actually, it has a 500GB usage cap and $.50/GB overage fee. Again, we have a metering provider who claims the overages were to penalize bandwidth hogs, yet then offer [faster] service, increasing overall load on their network, instead of just offering a fair amount of bandwidth per customer and eliminating overages by offering unlimited usage.”

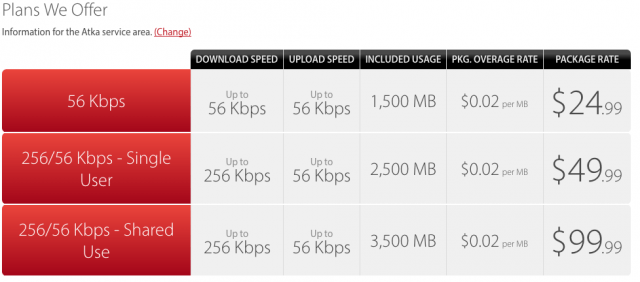

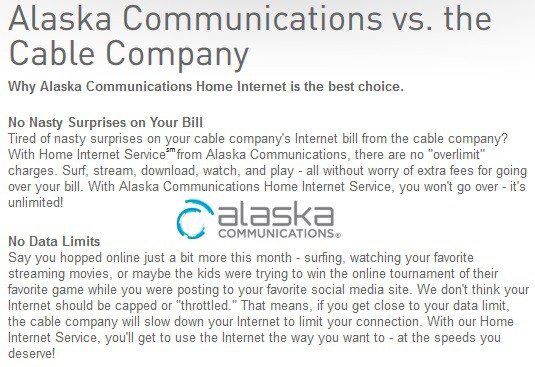

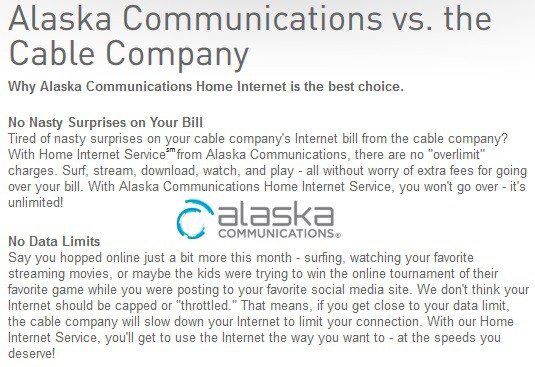

One of ACS’ strong selling points is no data caps, but DSL isn’t available to everyone.

In a filing with the FCC, ACS’ McDiffett suspects usage caps are all about the money.

“GCI reported 2012 Home Internet revenue of $86 million of which $7.9 million (nearly ten percent) was derived from overage charges,” said McDiffett. “On average, about $5 per customer per month can be attributed to GCI overage charges. GCI imposes usage limits or data caps at every level of Home Internet service, from its 10 Mbps service (10GB limit, $0.005/MB overage charge) to its 100 Mbps service (500GB limit, $0.0005/MB overage charge).”

Over time, and after several cases of bill shock, Alaskan Internet customers have become more careful about watching everything they do online, fearing GCI’s penalties. That threatens GCI’s overlimit revenue, and now Stop the Cap! readers report sudden, long-lasting problems with GCI’s usage checker, often followed by substantial bills with steep overlimit penalties they claim just are not accurate.

Over time, and after several cases of bill shock, Alaskan Internet customers have become more careful about watching everything they do online, fearing GCI’s penalties. That threatens GCI’s overlimit revenue, and now Stop the Cap! readers report sudden, long-lasting problems with GCI’s usage checker, often followed by substantial bills with steep overlimit penalties they claim just are not accurate.

“I currently pay $184.99 a month for GCI‘s highest offered broadband service. 200/5Mbps, with a 500GB monthly data cap,” shares Stop the Cap! reader Luke Benson. “According to GCI, over the past couple months our usage has increased resulting in overage charges at $1.00 a GB.”

In May, Benson was billed $130 in overlimit fees, but after complaining, the company finally agreed to credit back $100. A month later, they recaptured $60 of that credit from new overlimit fees. This month, Benson would have to unplug his modem halfway through his billing cycle or face another $50 in penalties.

GCI’s bandwidth monitor has proved less than helpful, either because it is offline or reports no usage according to several readers reaching out to us. GCI’s own technical support team notes the meter will not report usage until at least 72 hours after it occurs. GCI itself does not rely on its online usage monitor for customer billing. Customer Internet charges are measured, calculated, and applied by an internal billing system off-limits for public inspection.

“I have reached out to GCI multiple times asking for help, suggestions, resolution,” complains Benson. “All I get told is to turn down the viewing quality of Netflix, don’t allow devices to auto update, etc. They pretty much blamed every service but their own.”

Other customers have unwittingly fallen into GCI’s overlimit fee trap while running popular Internet applications that wouldn’t exist if GCI’s caps and overlimit fees were common across the country. Lifelong Bethel resident and tech consultant John Wallace knows the local horror stories:

Two girls had unwittingly allowed Dropbox to continuously sync to their computers, racking up a $3,500 overcharge in two weeks;

Two girls had unwittingly allowed Dropbox to continuously sync to their computers, racking up a $3,500 overcharge in two weeks;- One user’s virus protection updater got stuck on and it cost him $600;

- Wallace has heard people say, “I was gaming and I got a little out of hand and I had to pay $2,800;”

- Two six-year-old girls ran up $2,000 playing an online preschool game. Mom was totally unaware of what was going on, until she got the bill.

GCI’s own Facebook page was the home of a number of customer complaints until the complaint messages mysteriously disappeared. Stop the Cap! itself discovered it was not allowed to even ask questions on the company’s social media pages, apparently already on their banned list.

While GCI does well for itself and its shareholders, Wallace worries about the impact GCI’s control of the Alaskan Internet High Speed Internet market will have on the economy and Alaskan society.

“It’s about equal access and opportunity,” Wallace told Business Insider. “The Internet was meant to improve the lives of people in rural Alaska, but – because of the data caps and the sky-high overage fees – it ends up costing them huge amounts of money. We have one of the highest unemployment rates in the nation, and some of the highest rates of suicide, sexual assault, and drug abuse. The people who can’t afford it are the ones that are getting victimized. It was supposed to bring access – true availability of goods and services – but it really just brought a huge bill that many can’t afford.”

Alaska’s largest cable company today unveiled changes to its Internet plans, ditching surprise overlimit fees in favor of a speed throttle.

Alaska’s largest cable company today unveiled changes to its Internet plans, ditching surprise overlimit fees in favor of a speed throttle.

Subscribe

Subscribe When Verizon Wireless finally fired up its network in Alaska in September of 2014, the writing was on the wall for at least one of Alaska’s homegrown wireless competitors.

When Verizon Wireless finally fired up its network in Alaska in September of 2014, the writing was on the wall for at least one of Alaska’s homegrown wireless competitors.

Alaska-based GCI has rolled out a free upgrade for customers in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, Ketchikan, Mat-Su Valley, and Sitka that delivers broadband speeds up to 250/10Mbps.

Alaska-based GCI has rolled out a free upgrade for customers in Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, Ketchikan, Mat-Su Valley, and Sitka that delivers broadband speeds up to 250/10Mbps.

Nearly 10 percent of GCI’s revenue is now earned from overlimit fees collected from Alaskan broadband customers who exceed their cable or wireless usage limits.

Nearly 10 percent of GCI’s revenue is now earned from overlimit fees collected from Alaskan broadband customers who exceed their cable or wireless usage limits.

Over time, and after several cases of bill shock, Alaskan Internet customers have become more careful about watching everything they do online, fearing GCI’s penalties. That threatens GCI’s overlimit revenue, and now Stop the Cap! readers report sudden, long-lasting problems with GCI’s usage checker, often followed by substantial bills with steep overlimit penalties they claim just are not accurate.

Over time, and after several cases of bill shock, Alaskan Internet customers have become more careful about watching everything they do online, fearing GCI’s penalties. That threatens GCI’s overlimit revenue, and now Stop the Cap! readers report sudden, long-lasting problems with GCI’s usage checker, often followed by substantial bills with steep overlimit penalties they claim just are not accurate. Two girls had unwittingly allowed Dropbox to continuously sync to their computers, racking up a $3,500 overcharge in two weeks;

Two girls had unwittingly allowed Dropbox to continuously sync to their computers, racking up a $3,500 overcharge in two weeks;

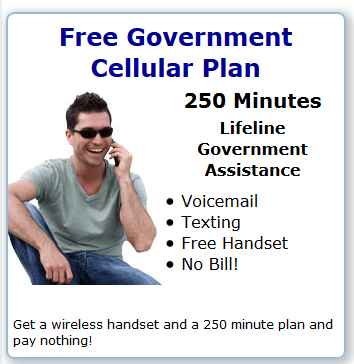

The case illustrated several ostensibly-independent companies were created to market service across Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. Many had ties back to AMTS management. Despite the Florida settlement, the firms continued to do business in multiple states. Many of the states involved have deregulated the telephone business and have cut staff at state agencies tasked with oversight issues.

The case illustrated several ostensibly-independent companies were created to market service across Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin. Many had ties back to AMTS management. Despite the Florida settlement, the firms continued to do business in multiple states. Many of the states involved have deregulated the telephone business and have cut staff at state agencies tasked with oversight issues. Last week, government agents seized the vehicles from Biddix’s Melbourne-based pawn shop, Outdoor Gun and Pawn.

Last week, government agents seized the vehicles from Biddix’s Melbourne-based pawn shop, Outdoor Gun and Pawn.