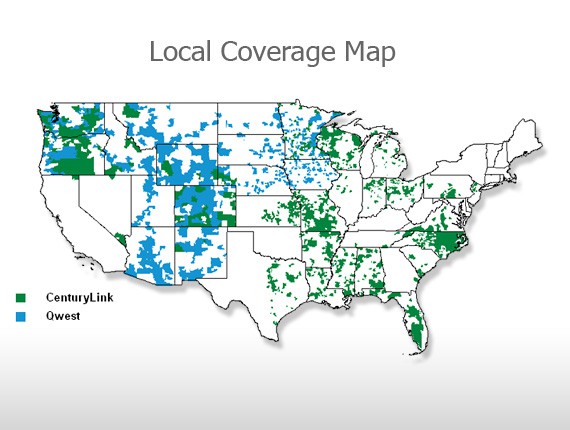

Today’s merger between CenturyTel (soon to be CenturyLink) and Qwest will combine 10 million Qwest customers and 7 million from CenturyTel into a single company serving 37 states in every region of the country except the northeast and much of California and Nevada. CenturyLink gains access to Qwest’s highly valued portfolio of services sold to business customers and Qwest gets a partner that can help manage its $11.8 billion debt and help grow the last remaining Baby Bell, formerly known as US West, into a national player capable of withstanding ongoing erosion of landline service.

Today’s merger between CenturyTel (soon to be CenturyLink) and Qwest will combine 10 million Qwest customers and 7 million from CenturyTel into a single company serving 37 states in every region of the country except the northeast and much of California and Nevada. CenturyLink gains access to Qwest’s highly valued portfolio of services sold to business customers and Qwest gets a partner that can help manage its $11.8 billion debt and help grow the last remaining Baby Bell, formerly known as US West, into a national player capable of withstanding ongoing erosion of landline service.

The deal will impact consumers and businesses, and will challenge regulatory authorities to consider the implications of ongoing consolidation in the traditional telephone service marketplace. It brings implications for broadband service strategies for both companies, which we’ll explore in greater detail.

Breaking Up Was Too Hard to Do, So Let’s Put It Back Together

Ultimately, the genesis of this, and most of the other big telecom deals that we’ve witnessed over the past few years comes from the 1996 Communications Act, which deregulated large parts of the telecommunications industry and triggered a massive wave of consolidation that is still ongoing. That legislation was the antithesis of the 1984 court ruling which ultimately led to the breakup of AT&T and the Bell System monopoly in 1984. When President Clinton signed the 1996 bill into law, it allowed much of the Bell System to eventually recombine into two major entities:

- AT&T ultimately pieced itself back together with the acquisitions of:

BellSouth — serving the southeastern United States

Ameritech — serving the upper Midwest

SBC/Southwestern Bell — serving Texas and several southern prairie states

Pacific Telesis — serving California and Nevada

- Verizon became a regional powerhouse by combining:

NYNEX — serving New England and New York

Bell Atlantic — serving mid-Atlantic states

The remaining orphaned Baby Bell was US West, which comprised Mountain Bell serving the Rocky Mountain states, Northwestern Bell which covered the Dakotas, Minnesota, the prairie states not covered by SBC, and Pacific Northwest Bell which managed service for Oregon, Washington, and northern Idaho. US West was subjected to a hostile takeover in 2000 by an upstart telecommunications company that was laying fiber optic cable in the late 1990s alongside the railways its owner, Philip Anschutz, also happened to own. Qwest assumed control of US West that summer and rechristened it with its own name. Owned by a Bell outsider, Qwest has always been the company that didn’t quite fit with the rest.

The company gained respect for its enormous fiber backbone that weaves across many American cities, including several in the northeast. It is best known for its services to business customers. On the residential side, the story is less impressive. The company’s customer service record is spotty and the company has accumulated an enormous amount of legacy debt left over from earlier acquisitions. Despite the company’s repeated efforts to find a partner, it took until today for it to finally find one. There are several reasons for this:

- Qwest’s service area is notoriously rural and expensive to serve. Outside of its corporate headquarters in Denver, the majority of its service area is either mountainous or rural. Even today, Qwest serves only 10 million residential customers, almost matched by CenturyTel’s own seven million largely rural customers scattered across the country.

- Qwest’s history has been littered with financial scandals, starting with a series of deals with disgraced Enron from 1999-2001. That was followed with charges of fraud and insider trading in 2005.

- Qwest does not own its own wireless division and its previous efforts to deliver television service to customers were largely unsuccessful. That made Qwest’s ability to withstand erosion in its core business – landline phone service, more difficult.

- Qwest’s debt is downright frightening for would-be suitors.

Why Does CenturyTel Want to Buy Qwest?

CenturyTel claims such a transaction allows a combined company to become a larger player on the national scene. By combining Qwest’s good reputation in the business telecommunications sector with combined efforts to deliver broadband products including high speed Internet, the company thinks the combination can’t be beat. CenturyTel envisions packages of video entertainment, data hosting and managed services, as well as fiber to cell tower connectivity and other high bandwidth services to deliver replacement revenue lost from disconnected landlines. It also believes it can realize cost savings from the merger and keep the company relevant on a stage dominated by Verizon, AT&T, and a few large cable companies.

But there are other reasons. For the three super-sized independent phone companies that Americans are growing increasingly familiar with — Frontier Communications, Windstream Communications, and CenturyTel, their business models depend on their ability to constantly engage in deal-making and acquisitions. All three companies have built their businesses on investors who see their stocks as “investment grade” financial instruments that dependably return a dividend back to shareholders. As we’ve seen in countless quarterly financial results conference calls, all three companies are preoccupied answering questions from Wall Street about the all-important dividend. TV personalities like Jim Cramer has specifically recommended these telecom stocks based, in part, on their dividend payout. If that dividend dramatically shrunk or stopped, the share price for all three stocks would likely plummet.

One of the side effects of companies dependent on dividend payouts is their constant need to be on the lookout for additional merger and acquisition opportunities. Here’s how it works. Let’s say CenturyTel’s debt load and reduced revenue, caused by customer defections to cell phones or cable phone service, delivered a bad fiscal quarter for the company. Cash flow was down, and company officials simply couldn’t keep the dividend payout at the same level as the previous quarter. Since many people hold CenturyTel stock specifically because of the dividend, a downward turn in that payout could cause some to sell their shares, driving the stock price downwards.

CenturyTel is still digesting a previous merger with EMBARQ, which led it to rechristen the company CenturyLink

One way around this is to seek out a new merger or acquisition target. By bringing two companies together, preferably one with a healthy cash flow, suddenly the big picture changes. Your balance sheet now reflects the combined revenue from both companies, which incidentally makes the percentage of debt versus revenue look a lot healthier. Cash flow immediately improves, especially if you can slash redundant costs. Come next quarter, that dividend payout is right back up in healthy territory.

Sometimes companies become so preoccupied with their dividend and corresponding stock price, it can lead them to pay out more in dividends than a company earns in revenue. While that’s great for investors, it is unsustainable in the long run.

Many critics of telecommunications companies employing this strategy claim it’s evidence that a company is biding time and unwilling to invest in innovation for the future. Some also believe dividend payouts shortchange customers because they can eventually bleed a company’s ability to invest in service improvements, research and development, and capital investments to maintain their network and expand service.

As consolidation continues, the number of new buyout opportunities begins to shrink, and one shudders to think what happens when there is no one else to buy. How long is this business model sustainable?

Both CenturyTel and Qwest also recognize the impact of ongoing disconnections from landline service, now averaging 10 percent of their customers a year. Those departing customers are now relying on their cell phones or alternative calling services like cable company “digital phone” service or broadband-based calling from companies like Vonage or Skype.

The one service they hope can stem customer defections is broadband. Unfortunately, telephone companies are increasingly losing ground against their cable modem competitors, who have an easier time increasing broadband speeds for customers now seeking online video and other high bandwidth applications.

Of course, one of the benefits of being a “rural phone company” is the fact cable competition is often unlikely. In fact, some of the lowest erosion rates for landline service are in rural communities where the telephone company is the only game in town. There is plenty of money still to be made offering high priced slow speed DSL service in communities with no cable competitor and spotty wireless broadband that is often slower and usage-limited.

All three of these big independent players are well aware of this, and maintaining a strong position in relatively slow speed DSL service also protects another revenue stream — Universal Service Fund revenue given to rural providers to equalize telephone rates. CenturyTel recognizes the increasing likelihood much of that money will be diverted to stimulating broadband expansion, something the phone company is more than willing to do if it means preserving their subsidies.

The new combined Qwest-CenturyTel company hopes the merger can help both survive obsolescence.

For Qwest, a debt reduction may make it possible to spend more to deliver fiber-to-the-curb service, similar to AT&T U-verse. That could increase broadband speeds and prompt them to reconsider their earlier decision to abandon IPTV in the western half of the country.

CenturyTel can continue to offer traditional DSL service with a more incremental upgrade approach in its more rural service areas, but tap into Qwest’s fiber network to reduce backhaul expenses and potentially pick up new business customers by offering Qwest-branded business services. Company officials strongly hinted that, at least for now, CenturyTel’s existing customers will continue to find the video portion of their “triple play” package delivered by DirecTV satellite service, so no IPTV for them.

What Does This Mean for Employees of Both Companies?

Mergers like this always generate great excitement over “cost savings” made possible by the merger. Much of these savings typically come from employee expenses. When you hear “cost savings,” think layoffs and pay cuts for all but top management. Based on past precedent, Qwest employees can anticipate some serious job losses if this transaction closes, especially in the business office. The combined company will be henceforth known as CenturyLink, with headquarters remaining in Monroe, Louisiana. That is potentially bad news for Qwest’s employees in Denver.

The transaction is expected to generate annual operating cost savings (which CenturyTel calls “synergies”) of approximately $575 million, which are expected to be fully realized three to five years following closing. The transaction also is expected to generate annual capital expenditure “synergies” of approximately $50 million within the first two years after close. That means spending less on infrastructure improvements.

Billing and customer service are traditionally handled by CenturyTel when a company joins the CenturyTel family. North Carolina customers can attest to that as EMBARQ, an earlier CenturyTel target, finally moves to CenturyTel’s billing system in the coming weeks.

For the sake of pushing the merger through state regulatory agencies, cutbacks in unionized technicians who handle service installations, repairs, and maintain the lines are not expected. The Communications Workers of America issued a statement today that mildly acknowledged the merger announcement, saying the union “looked forward to serious negotiations with both companies” regarding employment security and assurances of aggressive high speed broadband rollout throughout both companies’ territories.

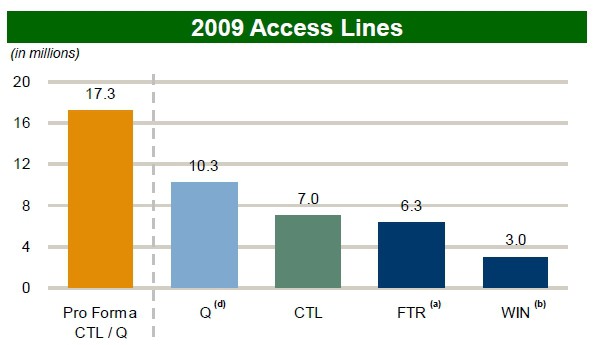

How the combined CenturyTel-Qwest company stacks up against other independent phone companies. (Q-Qwest, CTL-CenturyTel, FTR-Frontier, WIN-Windstream)

What Does This Mean for Qwest and CenturyTel Customers?

In the short term, nothing. This merger will take at least a year to complete, assuming regulatory approval in every state where a review is required by state officials. In 2011, should the merger be approved, Qwest customers can anticipate transition headaches as the Denver-based company winds down operations in favor of CenturyTel. Billing and customer service will both be impacted. Long term plans for major projects are likely to be stalled until the merger settles into place. CenturyTel business customers will eventually see Qwest’s strong business products line become available in many CenturyTel service areas. Eventually, some larger CenturyTel-served cities may find Qwest’s more advanced DSL service arriving on the scene delivering faster speeds.

Although CenturyTel has hinted it may review whether it’s now large enough to operate its own wireless mobile division, for the near term, expect the partnership to resell Verizon Wireless service to continue.

What is the View of Stop the Cap! on the CenturyTel-Qwest Merger?

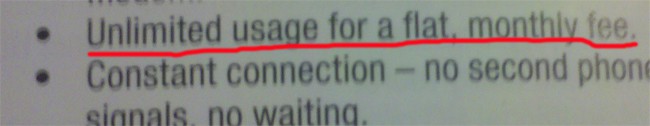

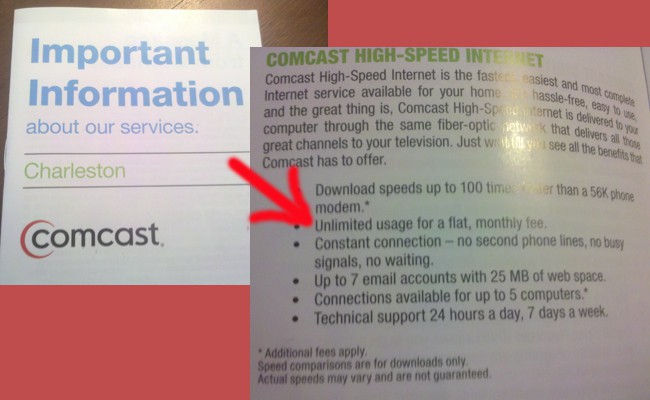

Generally speaking, most of the industry consolidation that has been fueled by a deregulatory framework established by the Clinton Administration has not benefited consumers anywhere near the level promised by deregulation advocates. The three largest independent phone company consolidators — Frontier, Windstream, and CenturyTel are spending more time and resources looking for new acquisitions and schemes to pay out dividends than they are working to enhance service in their respective service areas. Smaller independent phone companies are deploying fiber to the home networks and answer to the communities where they work and live. From companies like Frontier, we get Internet Overcharging schemes combined with slow DSL service, tricks and traps from “price protection agreements” that automatically renew, rate increases, and cost cutting. Windstream plagues some of their customers with extended service outages, and CenturyTel’s promised broadband speeds often don’t deliver.

Unfortunately, bigger is not always better in telecommunications. While the biggest players like Verizon seek to discard rural American customers, getting one of these three companies instead doesn’t always represent progress. Our regulators are too often satisfied with basic answers to questions about broadband and service improvements that come with few details and deadlines. It is just as important to ask what kind of broadband service a company will bring, at what speeds and price, and what usage limits, if any, will accompany the service.

Companies engaged in these mergers hope regulators don’t pin them down to specific service commitments and standards, which could harm the financial windfall these deals bring to a select few. But they must be the first thing on the table, guaranteeing that customers also get the enjoy the “synergies” these deals are supposed to bring.

Subscribe

Subscribe