The employees of Sonic.net, a California ISP that threatens to expose the chasm between the cost of providing broadband and the profits reaped from it.

It doesn’t take trillions of dollars to offer world class broadband service in America. Companies large and small are building gigabit broadband networks to reach customers at prices your local phone or cable company would charge at least $1,000 a month or more to receive, if you consider many charge around $100 a month for 100Mbps. Now, 700 families in California are going to be offered 1,000Mbps service for just $69.99 per month — including a phone line.

Sonic.net has been in the ISP business for more than 15 years, selling DSL service to California customers at prices that offer value for money. Most recently, Sonic has been pitching bonded DSL service offering speeds upwards of 40Mbps for the same price it plans to sell its new Fusion gigabit fiber broadband. For customers who don’t need that much speed, Sonic recently reduced the price for its 20Mbps service to $39.95 per month (including phone line.)

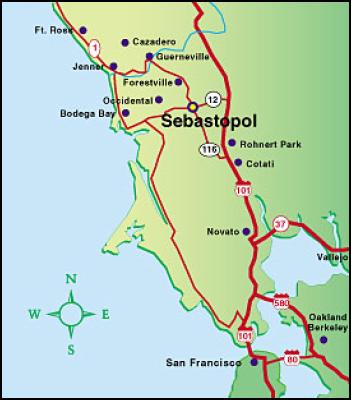

For those in the Sebastopol area lucky enough to qualify for fiber service, Sonic promises unlimited access and an exceptional online experience.

Sonic’s qualifications to run the project are not in question, considering Google selected the company to operate and support the trial fiber-to-the-home network the search giant is building at Stanford University.

Google itself is building an extensive fiber to the home network to serve Kansas City residents and businesses, and promises service at a profitable, but reasonable price. So has Sonic.net CEO Dane Jasper, whose written views on the state of American broadband explains his personal drive to make Internet access better and faster, without ripping people off with Internet Overcharging schemes or unjustified high monthly prices.

Jasper recognizes much of North America is trapped in a broadband duopoly that delivers all of the benefits to investors, while leaving the continent saddled with slow and overpriced service. Nine months ago Jasper explained the business model to Benoit Felten, a Yankee Group broadband analyst:

During the construction of this network we have given a lot of thought… to the business model in the US, and how we could do things in a different and more interesting way. The natural model when you have a simple duopoly capturing the majority of the market is segmentation: maximize ARPU [average revenue per user] by artificially limiting service in order to drive additional monthly spending. But fundamentally this is the wrong model for a service provider like us, and we have looked to Europe for inspiration. The model pioneered by Iliad under the Free brand is a better fit, both for us and for our customers.

As the marginal cost of providing more bandwidth or less, and providing [phone service] or not are both minimal, we have adopted a simple flat rate model instead of the more typical US model of “$5 more goes faster”… I believe that removing the artificial limits on speed, and including home phone with the product are both very exciting.

It’s exciting to customers as well, most who give the company nearly five star reviews for excellence, without five-star pricing. An added bonus: Jasper occasionally responds to customer service inquiries himself.

It’s exciting to customers as well, most who give the company nearly five star reviews for excellence, without five-star pricing. An added bonus: Jasper occasionally responds to customer service inquiries himself.

Reviewing Sonic.net’s blogs and website shows off a company that loves the business it’s in. If a switch 100 miles away has a problem that interferes with Sonic’s service, you will promptly read about it on the company’s technical blog.

There are houses for sale in Sebastopol, Calif., if you want affordable gigabit broadband.

Jasper’s frustration with the enormous corporate-owned ISPs that dominate the country (and Washington) was on full display in a blog entry in March, answering a question about why American broadband is lagging behind:

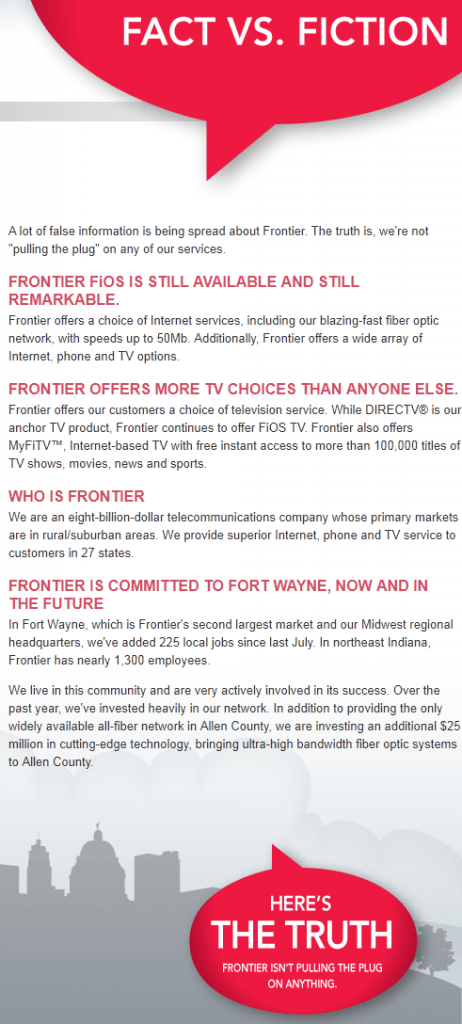

[…] In 2003 and 2004, the then Republican led FCC reversed course [on policies guaranteeing a level playing field for broadband], removing shared access to essential fiber infrastructure for competitive carriers and codifying instead a policy of exclusive use and “multi-modal competition”.

This concreted our unique US duopoly: cable versus telco, the two broadband choices that most Americans have today.

In exchange for a truly competitive market, the US received promises of widespread deployment. And, to some degree this has worked. Unfettered by significant competition or price pressure, broadband in at least in its most basic form can now be delivered to most homes in America, albeit at a comparatively high cost to the consumer.

What was given up in exchange for this far-reaching but mediocre pablum was true competition and innovation.

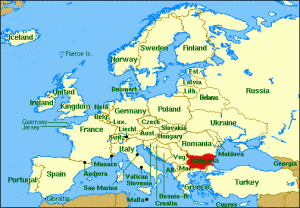

Elsewhere in the world, regulatory bodies followed the lead of the US Congress and separated essential copper and fiber infrastructure from the services and providers who used them, and the result has been amazing. In Asia and Europe, Gigabit services are becoming common, and the price paid by consumers per megabit is a tiny fraction of what we pay here at home.

I won’t deny the innovation that has occurred in the telco/cable duopoly. They’ve got TV, Internet and telephone bundles designed to serve up prime time network shows in over-saturated HD glory, with comparatively middling Internet speeds, all offered with teaser rates and terms that would baffle an economics professor. The clear value of the bundle is to baffle, and pity the consumer who wants to shed a component. At least during the intro periods, it’s often cheaper to take the whole package than just a component or two.

For cable companies, the entrenched interest in the television entertainment portion creates a clear conflict: why should they offer an uncapped broadband connection that can deliver enough video entertainment to allow consumers to cut the TV cord? And if you do drop the TV, up goes the price for even this slow and capped Internet connection, so you pay more either way. And now that telcos have gotten into the television business too, their interest in slowing the pace of increasing broadband speed is aligned as well.

This has yielded a competitive truce in America.

In a slow tide, back and forth, cable delivers a slightly better product, then telco slightly better again, all at the highest possible cost. It is iterative, not innovative, and Americans deserve more. After all, we invented the Internet, right?

Among the giant phone and cable companies providing broadband today are a growing number of innovation outliers — companies challenging the prevailing views that Americans don’t need or want fiber-fast speeds (not at the prices some providers charge), that there is no economic justification for the capital spending required to construct fiber networks when incremental upgrades can suffice (the Wall Street view), or that the best way to drive increased revenue from a maturing broadband market is to throw away today’s flat rate pricing model and establish a guaranteed growth fund collecting tolls on Internet traffic that is sure to rise in the days ahead (Time Warner Cable’s CEO).

Google cannot understand why 1Gbps broadband “doesn’t work” in the United States and intends to construct its own network to prove otherwise. EPB, a municipal utility in Chattanooga, Tenn. sells gigabit broadband, in their words, because they can. The concept of a provider offering the fruits of their innovation, even if they aren’t certain how to price or sell the service, is a remarkable and refreshing change from the usual obsession with nickle-and-dime “extras” for add-on features or not selling service that your marketing department does not understand or find useful.

It also exposes the indefensible gap between the cost of providing the service and the price paid to receive it.

Thanks to Stop the Cap! reader Mark for sharing news about Sonic.net’s fiber network.

Bulgaria’s capital city, Sofia, will be blanketed in fiber-to-the-home broadband by the year 2014, according to Bulgarian Internet provider EVO.bg. The company is investing $860 million to roll out its fiber network, which it says will deliver some of Europe’s fastest broadband speeds.

Bulgaria’s capital city, Sofia, will be blanketed in fiber-to-the-home broadband by the year 2014, according to Bulgarian Internet provider EVO.bg. The company is investing $860 million to roll out its fiber network, which it says will deliver some of Europe’s fastest broadband speeds. Today, broadband demand is causing a usage explosion, and companies are upgrading their networks to meet the challenges customers bring.

Today, broadband demand is causing a usage explosion, and companies are upgrading their networks to meet the challenges customers bring.

Subscribe

Subscribe