Verizon Communications and AT&T together represent the largest providers of legacy copper wire landline phone service in the United States. Over the past ten years, the traditional landline business has taken a beating as consumers increasingly turn their backs on the technology Alexander Graham Bell helped invent more than 100 years ago. No utility service faces more customer defections than the phone company, and providers are increasingly rewriting their business models or lobbying to abandon unprofitable service areas altogether.

Verizon Communications and AT&T together represent the largest providers of legacy copper wire landline phone service in the United States. Over the past ten years, the traditional landline business has taken a beating as consumers increasingly turn their backs on the technology Alexander Graham Bell helped invent more than 100 years ago. No utility service faces more customer defections than the phone company, and providers are increasingly rewriting their business models or lobbying to abandon unprofitable service areas altogether.

For some customers, investments in network improvements have brought advanced fiber optics straight to the home. But in smaller communities, customers are making due with a deteriorating network phone companies no longer want to maintain.

The Glorious Growth Years

Back in the late 1980s, before most of us realized there was an Internet (or that you might be able to access it from home), the concept of connecting computers together to share information meant buying a 300-1200bps modem and using your home phone line to dial up hobbyist computer bulletin boards, CompuServe, PeopleLink, Delphi, GEnie, and QuantumLink.

Landline service was never perfect, but it worked reliably enough to make and receive phone calls and connect to low speed data networks. As the 1990s arrived, an explosion in data and wireless services would bring both growth and unprecedented challenges for traditional telephone companies. Businesses demanded access to additional phone lines to power dedicated data lines and fax machines. Residential customers wanted extra phone lines as well, mostly to keep data traffic off the primary house line. It was the era of frenzied area code splits, cell phones for all, and talk America could even run out of seven digit phone numbers to assign to all of the new lines.

NYNEX is today known as Verizon

As revenue and earnings exploded with the installation of new voice, data, and fax lines, Wall Street investors soon took notice. Sleepy and safe phone company stocks were suddenly hot, and a deregulation-fueled consolidation frenzy soon resulted as phone companies merged and acquired one another. Among the Bell System operating companies, familiar names like NYNEX, Bell Atlantic, BellSouth, Southwestern Bell, Pacific Telesis, Ameritech, and US West were gone, replaced by AT&T, Qwest, and Verizon. Independent phone companies were not immune to the merger and acquisition game. Today’s largest independent phone companies including Frontier Communications, CenturyLink, FairPoint, and Windstream have all grown mostly through buyouts of other providers.

The Bottom Drops Out

The rapid growth years of the traditional wired phone line came to an end around the same time as the dot.com crash and accompanying recession from 2000-2002. While cell phone growth would continue, new competitors — especially cable-delivered “digital phone” service and other Voice Over IP providers like Vonage seriously cut into market share and revenue. The need for additional phone lines to access the Internet subsided with the growth of DSL and cable broadband. As household income stagnated, choices began to be made about where to cut back, and the traditional landline was a popular favorite. Why pay for both a landline and a cell phone? The cell phone stayed, the landline went. Even dedicated fax machines are increasingly deemed unnecessary in an e-mail world.

The growing realization that the traditional copper wire telephone line was at risk of being the next “horse and buggy business” forced companies to consider a handful of options: ride out the landline declines and lower shareholder expectations, transform their existing networks to sustain new products like faster broadband and television service to give customers reasons to stay, or transition focus on business customers who bring more revenue.

AT&T and Verizon have adopted all three strategies, depending on where customers happen to live.

AT&T: If You are Still Waiting for DSL From Us, Forget It

AT&T: If You are Still Waiting for DSL From Us, Forget It

In October, John J. Stephens, chief financial officer and executive vice-president at AT&T made it clear to investors the company’s interest in growing its legacy wired business had come to an end. The company had lost landline customers for years, most switching to cell phone alternatives, sometimes sold by AT&T itself. Spending enormous sums to upgrade AT&T’s copper landline network just didn’t make financial sense in every area. Instead, AT&T split its operating territories in two: those suitable for upgrades to the company’s U-verse/IP platform, and those in smaller communities who will soon find themselves pushed to switch to AT&T wireless service instead. That makes the prospects for customers still waiting for wired DSL service from AT&T pretty dim.

“We’ll continue to focus on transforming [existing] DSL lines into high speed [U-verse].” Stephens said. “In those areas where we don’t have U-verse, I think our plans have been fairly clear. We expect to have an LTE [wireless mobile broadband] rollout to 97% of the country. […] We believe that’s going to be able to provide a wireless solution at a high speed, good quality, good cost on a profitable basis for us. That’s the long-term solution to the non-U-verse areas.”

AT&T’s lobbyists have signaled this agenda for years, pressing state and federal lawmakers to get rid of “universal service” requirements that mandate reliable, basic landline telephone service to any customer in their service area who requests it. AT&T wants the definition of “basic telephone service” expanded to allow the company the option of discontinuing its landline network and selling rural residents cell phone service instead. The expense associated with maintaining AT&T’s degrading copper wire network is always cause for grumbling on Wall Street, most recently after this year’s repair costs from storms that impacted some of AT&T’s service areas. Storm damages brought outages in the southern United States, flooded regions along the Mississippi, and rained-out areas of California.

Those problems were exacerbated when AT&T’s repairs don’t always correct the problems. Repeated outages blamed on inadequate repairs and investment brought negative publicity for the phone company, as well as a number of requests to disconnect service as customers find other providers.

In places where AT&T will never deploy U-verse, AT&T has been content asking lawmakers to ease up on the phone company, urging that minimum service standards and oversight be abolished, along with the power of regulators to fine the company for repeated transgressions. AT&T argues increased competition makes regulation unnecessary.

AT&T: Wants to eliminate universal service for rural America.

AT&T’s bean counters have calculated investment in U-verse only makes sense in urban-suburban areas. In more distant suburbs and rural areas, the return on investment isn’t fast enough to justify spending money up-front on service improvements. Maintaining the decades-old landline network doesn’t make much sense to AT&T either. Instead, the company sees wireless service as the best prospect to serve its rural customers (and deliver the company higher profits from the more expensive service plans that come with the phones).

“What I see happening with LTE and data is just a huge growth opportunity,” said Ralph de la Vega, CEO and president of AT&T Mobility & Consumer Markets. “We mentioned today that our smartphones now make up 52% of our postpaid base. But I think the way we need to think about smartphones in the future is the smartphone is going to equal the phone in the future. It will be 100% in the next 2 or 3 years. These devices are so good and the costs are coming down so much that I think in the future, you could look at close to 100% penetration.”

Some customers may find AT&T penetrating their wallets, but for the phone company, better days may be ahead:

- Moving customers to the wireless platform exposes them to higher revenue, higher-priced wireless service plans;

- Basic cell phones, which come with lower-priced voice plans are being increasingly replaced with smartphones which come with required, extra-cost data plans;

- Getting rid of the rural landline network slashes AT&T’s upkeep costs and holds customers in place with two-year service contracts common with wireless phones.

Consumers happy with their existing landline service may be less than impressed with AT&T’s cellular network coverage, its dropped call-problem, and the company’s alternative for rural broadband – heavily usage-capped and expensive LTE network access. AT&T sells wired DSL plans for as little as $14.95 a month with a 150GB usage limit. AT&T’s wireless LTE network will cost considerably more and is accompanied with usage limits a fraction of that amount.

Verizon: A Tale of Two Networks

Verizon: A Tale of Two Networks

Big Red has two wired landline networks: screaming fast FiOS fiber to the home for some, slow speed DSL over a decrepit copper wire network for everyone else.

Verizon is less opaque than AT&T regarding which service areas it treats as valued assets and which aren’t worth the time of day. The company began selling off its undesirable customers several years ago, starting with Hawaii. Northern New England was next, followed by several former GTE territories Verizon acquired in 2000.

While Verizon enjoyed the proceeds of the tax-free transactions, most of the impacted customers did not. Hawaiian Telcom floundered for a few years with bad service and an outrageous debt load before declaring bankruptcy. Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont suffered through a year-long transition to buyer FairPoint Communications, complete with poor service and notoriously inaccurate billing before that company also declared bankruptcy. Former Verizon customers in the Pacific Northwest, Indiana, and West Virginia (among others) are coping with Frontier Communications own billing and service problems.

The FairPoint Trust called the $2.3 billion acquisition of Verizon’s New England operations “disastrous.” It also echoed what Verizon obviously understood itself: its landline operation in New England had been allowed to deteriorate into “inferior assets that had no future.”

Frontier Communications itself judged the network it purchased from Verizon in West Virginia in need of serious upgrades and repairs. Critics of the deal called Verizon’s West Virginia network “a technical disaster area.”

But while Verizon is capable of landline neglect, it is also the only major phone company delivering true fiber-to-the-home service over its award winning (and expensive to build) FiOS network.

The feast or famine approach Verizon has used for capital investments has resulted in amazing service for some, a loss of reliable service to many others.

FiOS has allowed Verizon to remain a serious player, particularly in the northeast, despite the onslaught of competition from Cablevision, Comcast, and Time Warner Cable. Average revenues earned from FiOS customers are much higher than what the company earns from customers on its copper wire telephone network.

Some Verizon shareholders have never liked the price for the company’s fiber future. When the economy tanked in late 2008, an indefinite suspension of FiOS expansion soon followed, leaving Verizon’s network expansion plans in limbo. The company is still slowly completing the portion of its fiber network promised under existing agreements, but has avoided introducing the service in new cities and towns. At the same time, Verizon is loathe to maintain investment in its antiquated copper wire landline network, which in some areas was supposed to be retired in favor of FiOS.

Bistro Chat Noir: Reliable Verizon phone service is not on the menu.

As long as Verizon’s older network can be held together, with fingers crossed, customers still have a dial tone. But when things start to fail, customers are in for serious headaches. They are popping aspirin almost daily at Bistro Chat Noir, a prestigious French restaurant along Madison Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. If you plan to dine there, it is best to bring cash. Even if the management wanted to take your Visa or Mastercard, the restaurant’s phone lines are out so often, they can’t easily process your payment.

These days, the resourceful owners rely on a neighbor’s graciously shared Wi-Fi connection (presumably powered by competitor Time Warner Cable) to process credit card transactions manually.

Waiting for FiOS

The New York Times wrote Verizon’s atrocious level of service isn’t isolated to one bistro:

“Obviously, this is not the way we want to do business,” said Ms. Latapie, who has started giving clients her personal cellphone number to avoid missing reservations when the restaurant’s phone is not performing properly. “When people can’t get through, I tell them it’s Verizon. And if they live in this area, they know — because they have the same problem.”

However irritating, sporadic utility failures are not uncommon. But along a a stretch of Madison Avenue in what is arguably the city’s most expensive shopping and eating district, phone and Internet blackouts have become a nightmarish routine of life for many expensive restaurants, stores and hotels.

For weeks now, mundane tasks — making dinner reservations and paying for purchases by credit card — have become a frustrating challenge.

“We are in the highest rent district in North America and we don’t have communication,” said Jillian Wright, whose spa on East 66th Street is on the second floor of a brownstone building and not ideal for walk-ins. Ms. Wright said she was losing clients daily, and her spa’s phone number goes straight to a voicemail message apologizing to clients for Verizon’s service.

The service failures have affected dozens of businesses, primarily in the East 60s along Madison Avenue. The scope of the problem varies, with some businesses having no phone or Internet service at all for the past several weeks and others experiencing blackouts that last days or a few hours.

Meetings with Verizon officials have deteriorated into spin-and-excuse sessions where company officials promise results but continue to deliver lousy service. It turns out the problem is Verizon’s ancient copper wiring found underneath the streets in the area. Just two feet away from Verizon’s cables are steam heating pipes, which warm the tunnels and create major condensation problems. Couple that with water runoff from the streets above — salt-laden in the winter time — and you have a recipe for corrosion that destroys reliable phone service.

Eventually, Verizon plans to wire FiOS fiber across a large section of Madison Avenue, but with the company’s unwillingness to invest appropriate sums to get the job done, business and residential customers are simply kept waiting.

Or they can switch to Time Warner Cable, and many are.

Your Telephone Is Temporarily Out of Service…

A traditional overhead phone cable is packed with cable pairs for neighborhood phone service

Verizon’s service woes are not just for big city dwellers. Residents in Virginia are coping with Verizon landline problems in suburban neighborhoods, too. Verizon employees openly admit they are fighting a losing battle with management to replace defective cables and equipment that should have been replaced years ago. Management keeps winning and customers keep losing.

“When we come to this area, we dread it,” admits Alex Long, a cable splicer at Verizon for 22 years.

Long just pulled up to a pole off Burksdale Road in Norfolk and found nothing he had not seen many times before — untrimmed tree branches overgrown into the overhead wires. The branches had managed to rub the phone cable’s insulation down to bare copper wire.

As a result, whenever it rains, telephone service in the neighborhood becomes sporadic. If tree branches don’t knock service out, cable-chewing squirrels do. The lines, the equipment, and the technology is well past its prime, but Verizon management insists repair crews fix what is already there instead of replacing it with something better. It’s all a matter of money, and Verizon wants to spend as little as possible on its copper landline network.

Long’s experiences were the highlight of a piece published by the Virginian-Pilot, which has heard complaints from readers about dreadful Verizon phone service across the region.

The repairman discloses Verizon technicians have known about the bad cable for at least five years, but requests to replace it have been repeatedly rejected.

“The cable’s totally shot,” Long told the newspaper. “It needs to be replaced, and the company’s budget doesn’t allow for it. That’s what engineering keeps telling us.”

In Hampton Roads, Va., it is a case of the fiber haves and have nots. The parts of Hampton Roads that have been upgraded to Verizon’s fiber to the home network are virtually trouble-free in comparison to neighborhoods where copper cables still deliver service. Verizon’s legacy network is of such concern, the Virginia State Corporation Commission has increasingly taken a close look at the level of service Verizon is providing in non-FiOS areas.

William Irby, director of the commission’s Division of Communications, has heard plenty of concerns that Verizon is neglecting their copper network in favor of FiOS fiber.

William Irby, director of the commission’s Division of Communications, has heard plenty of concerns that Verizon is neglecting their copper network in favor of FiOS fiber.

Verizon’s copper wire neglect might not be such a big problem had the company provided a date certain for upgrade relief. But with FiOS expansion also stalled, some cities are now wondering if Verizon is abandoning them.

Boston is one of them.

Left Behind: The Cities Without FiOS

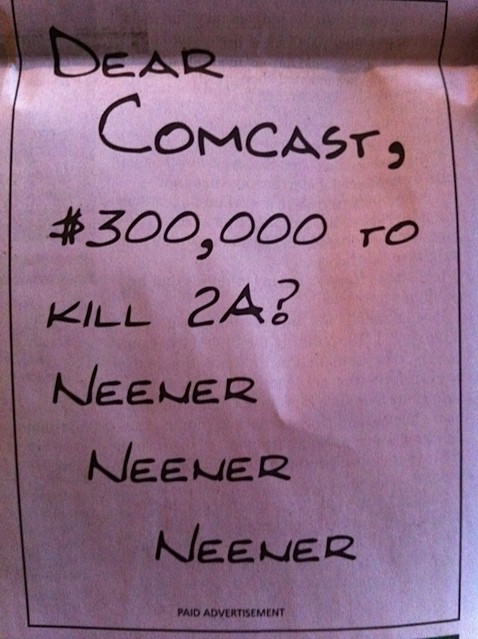

Verizon FiOS is well-known in eastern Massachusetts. There are those who have it and those who want it. Verizon had been aggressively pursuing franchise agreements with 111 communities across the state until the company announced it was putting on the brakes and ceasing further expansion efforts in new areas. That leaves Boston and other communities like Quincy behind because they didn’t sign agreements with the company fast enough.

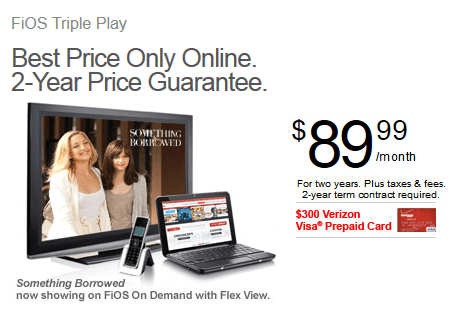

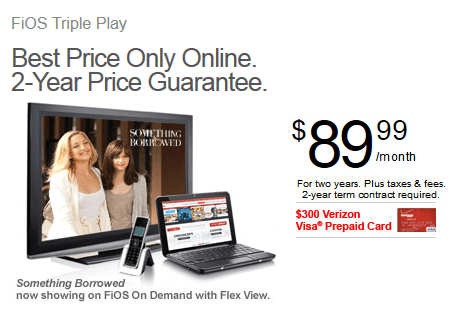

Verizon FiOS customers get the good life: $90 a month for a triple-play package with a $300 Visa debit card reward for signing up.

“If you’ve got FiOS, lucky you,” shares Quincy resident Roger Jones. “If you don’t, good luck.”

Jones says Verizon has left Quincy with a neglected landline network the company doesn’t seem interested in maintaining, much less replacing with fiber optics.

“The company believed in fiber optics because they saw the opportunities fiber could deliver, like additional revenue from selling TV channels,” Jones says. “But then Wall Street caught up to them and said it was all too much. I might even understand that, except they won’t spend a nickle maintaining what they already have either, unless the regulators twist their arms and threaten fines over the bad service.”

Jones says his Verizon phone line was out three times earlier this year.

“Three strikes and they were out — I switched to Comcast,” Jones says. “A Verizon repair guy that came to my house the third time said all of his relatives switched to Comcast because service got to be so unreliable with Verizon’s old network.”

Back on Burksdale Road in Norfolk, Long was trying to track down another customer’s phone troubles — a loud hum on their line. Hours later, Long decided it was a futile effort and began looking for an unused replacement pair of good wires he could switch to for the customer. With the growing number of Verizon customers disconnecting their landline service permanently, that task gets easier every day.

Long told the newspaper it was no surprise Burksdale Road customers were experiencing problems. Closures which were designed to protect the cable where it splits off individual phone lines were supposed to be water and air-tight. Instead, he was working with a deteriorating rubber enclosure that showed its age after years of service. Unfortunately, he explains, Burksdale Road customers will simply have to make due.

Not only won’t Long be able to replace the deteriorating infrastructure he finds, he’ll be forced to improvise with Verizon’s latest cost-cutting solution for wet cables — covering them with sheeting that resembles a plastic garbage bag. Even that is nothing new for Burksdale Road. Several houses down, a cable “rain-slicker” was already tightly wrapped around a section of cable where the rubber closure had gone missing altogether.

After getting the dial tone back, Long handed the customer his business card with his direct number and apologized.

“You may have problems again,” he said, advising the customer to call him directly the next time his phone line stops working.

Verizon better hope the customer doesn’t call the local cable company to switch providers or disconnect his landline altogether.

Bell Canada is misleading potential customers when mailing them invitations to sign up for Fibe TV, which the company calls “a new TV service delivered through our new state-of-the-art fibre optic network.”

Bell Canada is misleading potential customers when mailing them invitations to sign up for Fibe TV, which the company calls “a new TV service delivered through our new state-of-the-art fibre optic network.”

Subscribe

Subscribe