Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) will assume the leadership of the Senate Commerce Committee in January.

The Republican takeover of the U.S. Senate could have profound implications on U.S. telecommunications law as Congress contemplates further deregulation of broadcasting, broadband, and telecom services while curtailing oversight powers at the Federal Communications Commission.

Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), expected to assume leadership over the Senate Commerce Committee in January, has already signaled interest in revising the 1996 Communications Act, which was built on the premise that deregulation would increase competition in the telecommunications marketplace.

“Our staff has looked at some things we might do in the area of telecommunications reform,” Thune told Capital Journal.” That hasn’t been touched in a long time. A lot has changed. The last time that the telecom sector of the economy was reformed was 1996, and I think in that bill there was one mention of the Internet. So it’s a very different world today.”

Republicans have complained the 1996 Telecom Act is dependent on dividing up services into different regulatory sectors and subjecting them to different regulatory treatment. In the current Net Neutrality debate, for example, a major component of the dispute involves which regulatory sector broadband should be classified under — “an information service” subject to few regulations or oversight or Title 2, a “telecommunications service” that has regulatory protections for consumers who have few choices in service providers.

Republicans have advocated streamlining the rules and eliminating “broad prescriptive rules” that can have “unintended consequences for innovation and investment.” Most analysts read that as a signal Republicans want further deregulation across the telecom industry to remove “uncertainty for innovators.”

Republicans have been particularly hostile towards imposing strong Net Neutrality protections, particularly if it involves reclassification of broadband as a “telecommunications service” under Title 2 of the Communications Act. Most expect Thune and his Republican colleagues will oppose any efforts to enact Net Neutrality policies that open the door for stronger FCC regulatory oversight.

The move to re-examine the Communications Act will result in an enormous stimulation of the economy, if you happen to run a D.C. lobbying firm. Just broaching the subject of revising the nation’s telecommunications laws stimulates political campaign contributions and intensified lobbying efforts. From 1997-2004, telecommunications companies advocating for more deregulation spent more than $44 million in direct soft money and PAC donations — $18 million to Democrats, $27 million to Republicans. During the same period, eight companies and trade groups in the broadcasting, cable and telephone sector collectively spent more than $400 million on lobbying activities alone, according to Common Cause.

Reopening the Telecom Act for revision is expected to generate intense lobbying activity, as Congress contemplates subjects like eliminating or curtailing FCC oversight over broadband, how wireless spectrum is distributed to wireless companies, how many radio and television stations a company can own or control, maintaining or strengthening bans on community broadband networks, oversight of cable television packages, and compensation for broadcast stations vacating frequencies to make room for more cellular networks.

Common Cause notes ordinary citizens had little say over the contents of the ’96 Act and consumer group objections were largely ignored. When the bill was eventually signed into law by President Bill Clinton, its sweeping provisions affected almost every American:

Good times at K Street lobbying firms are ahead

BROADCASTING

- The 96 Act lifted the limit on how many radio stations one company could own. The cap had been set at 40 stations. It made possible the creation of radio giants like Clear Channel, with more than 1,200 stations, and led to a substantial drop in the number of minority station owners, homogenization of playlists, and less local news. Today, few listeners can tell the difference between radio stations with similar formats, regardless of where they are located.

- Lifted from 12 the number of local TV stations any one corporation could own, and expanded the limit on audience reach. One company had been allowed to own stations that reached up to a quarter of U.S. TV households. The Act raised that national cap to 35 percent. These changes spurred huge media mergers and greatly increased media concentration. Together, just five companies – Viacom, the parent of CBS, Disney, owner of ABC, FOX-News Corp., Comcast-NBC, and Time Warner now control 75 percent of all prime-time viewing.

- The Act gave broadcasters, for free, valuable digital TV licenses that could have brought in up to $70 billion to the federal treasury if they had been auctioned off. Broadcasters, who claimed they deserved these free licenses because they serve the public, have largely ignored their public interest obligations, failing to provide substantive local news and public affairs reporting and coverage of congressional, local and state elections. Many television stations have discontinued local news programming altogether or have relied on partnerships with other stations in the same market to produce news programming for them. Most local television stations are now owned by out-of-state conglomerates that control dozens of television stations and now expect to be compensated by viewers watching them on cable or satellite television.

- The Act reduced broadcasters’ accountability to the public by extending the term of a broadcast license from five to eight years, and made it more difficult for citizens to challenge those license renewals.

TELECOMMUNICATIONS

- The 1996 Act preserved telephone monopoly control of their networks, allowing them to refuse new entrants who depend on telco infrastructure to sell their services.

- The Act was designed to promote increased competition but also allowed major telephone companies to refuse to compete outside of their home territories. It also allowed Bell operating companies to buy each other, resulting in just two remaining major operators — AT&T and Verizon.

CABLE

- The ’96 Act stripped away the ability of local franchising authorities and the FCC to maintain oversight of cable television rates. Immediately after the ’96 Act took effect, rate increases accelerated.

- The Act permitted the FCC to ease cable-broadcast cross-ownership rules. As cable systems increased the number of channels, the broadcast networks aggressively expanded their ownership of cable networks with the largest audiences. In the past, large cable operators like Time Warner, TCI, Cablevision and Comcast owned most cable networks. Broadcast networks acquired much of their ownership interests. Ninety percent of the top 50 cable stations are owned by the same parent companies that own the broadcast networks, challenging the notion that cable is any real source of competition.

“Those who advocated the Telecommunications Act of 1996 promised more competition and diversity, but the opposite happened,” said Common Cause president Chellie Pingree back in 1995. “Citizens, excluded from the process when the Act was negotiated in Congress, must have a seat at the table as Congress proposes to revisit this law.”

“Those who advocated the Telecommunications Act of 1996 promised more competition and diversity, but the opposite happened,” said Common Cause president Chellie Pingree back in 1995. “Citizens, excluded from the process when the Act was negotiated in Congress, must have a seat at the table as Congress proposes to revisit this law.”

Above all, the legacy of the 1996 Telecom Act was massive consolidation across almost every sector.

Over ten years, the legislation was supposed to save consumers $550 billion, including $333 billion in lower long-distance rates, $32 billion in lower local phone rates, and $78 billion in lower cable bills. But most of those savings never materialized. Indeed, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who opposed the legislation, noted in 2003: “From January 1996 to the present, the consumer price index has risen 17.4 percent … Cable rates are up 47.2 percent. Local phone rates are up 23.2 percent.”

Advocates of deregulation also promised the Act would create 1.4 million jobs and increase the nation’s Gross Domestic Product by as much as $2 trillion. Both proved wrong. Consolidation meant the loss of at least 500,000 “redundant” jobs between 2001-2003 alone, and companies that became indebted in the frenzy of mergers and acquisitions ended up losing more than $2 trillion in the speculative frenzy, conflicts of interest, and police-free zone of the deregulated telecom marketplace.

The consolidation has also drastically reduced the number of independent voices speaking, writing, and broadcasting to the American people. Today, just a handful of corporations control most radio and TV stations, newspapers, cable systems, movie studios, and concert ticketing and facilities.

The law also stripped away oversight of the broadband industry which faces little competition and has no incentive to push for service-enhancing upgrades, costing America’s leadership in broadband and challenging the digital economy. What few controls the FCC still has are now in the crosshairs of large telecom companies like AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon.

All are lobbying against institutionalized Net Neutrality, oppose community broadband competition, regulated minimum speed standards, and service oversight. AT&T and Verizon are lobbying to dismantle the rural telephone network in favor of their much more lucrative wireless networks.

Consumers Union predicted the outcome of the 1996 Telecom Act back in 2000, when it suggested a duopoly would eventually exist for most Americans, one dedicated primarily to telephone services (AT&T and Verizon Wireless’ mobile networks) and the other to video and broadband (cable). The publisher of Consumers Reports also accurately predicted neither the telephone or the cable company would compete head to head with other telephone or cable companies, and High Speed Internet would be largely controlled by cable networks using a closed, proprietary network not open to competitors.

Analysts suggest a 2015 Telecom Act would largely exist to further cement the status quo by prohibiting federal and state governments from regulating provider conduct and allowing the marketplace a free hand to determine minimum standards governing speeds, network performance, and pricing.

In fact, the most radical idea Thune has tentatively proposed for consideration in a revisit of the Act is his “Local Choice” concept to unbundle broadcast TV channels from all-encompassing cable television packages. His proposal would allow consumers to opt out of subscribing to one or more local broadcast television stations now bundled into cable television packages.

Subscribe

Subscribe The majority of 3.7 million comments received by the FCC advocate strong and unambiguous Net Neutrality protections for the Internet, but that seems to have had little impact on FCC chairman Thomas Wheeler, who is laying the groundwork for a hybrid Net Neutrality Frankenplan that would marginally protect deep pocketed content producers while leaving few, if any, protections for consumers.

The majority of 3.7 million comments received by the FCC advocate strong and unambiguous Net Neutrality protections for the Internet, but that seems to have had little impact on FCC chairman Thomas Wheeler, who is laying the groundwork for a hybrid Net Neutrality Frankenplan that would marginally protect deep pocketed content producers while leaving few, if any, protections for consumers. Large telecommunications companies argue that deregulation promotes broadband investment and expansion to create world-class service. But years of statistics and comparisons with other countries suggest deregulation has not inspired sufficient competition to keep prices in check and force regular network upgrades. In fact, competition is much more robust at the wholesale level, while the majority of retail consumers have a choice of just one or two providers that receive almost no oversight. Those providers are now exercising their market power to further monetize broadband usage to boost profits and raise prices.

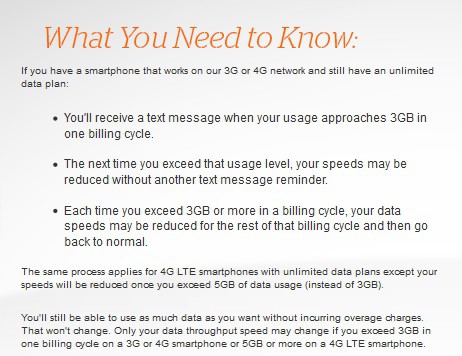

Large telecommunications companies argue that deregulation promotes broadband investment and expansion to create world-class service. But years of statistics and comparisons with other countries suggest deregulation has not inspired sufficient competition to keep prices in check and force regular network upgrades. In fact, competition is much more robust at the wholesale level, while the majority of retail consumers have a choice of just one or two providers that receive almost no oversight. Those providers are now exercising their market power to further monetize broadband usage to boost profits and raise prices. The Federal Trade Commission today filed a lawsuit against AT&T for its practice of subjecting grandfathered unlimited data customers to speed throttles that dramatically cut speeds up to 90 percent after customers use more than 3GB of data on AT&T’s 3G network or 5GB on its 4G network. Thus far, according to the FTC, AT&T has throttled at least 3.5 million unique customers a total of more than 25 million times.

The Federal Trade Commission today filed a lawsuit against AT&T for its practice of subjecting grandfathered unlimited data customers to speed throttles that dramatically cut speeds up to 90 percent after customers use more than 3GB of data on AT&T’s 3G network or 5GB on its 4G network. Thus far, according to the FTC, AT&T has throttled at least 3.5 million unique customers a total of more than 25 million times.

The Federal Communications Commission announced Friday it will

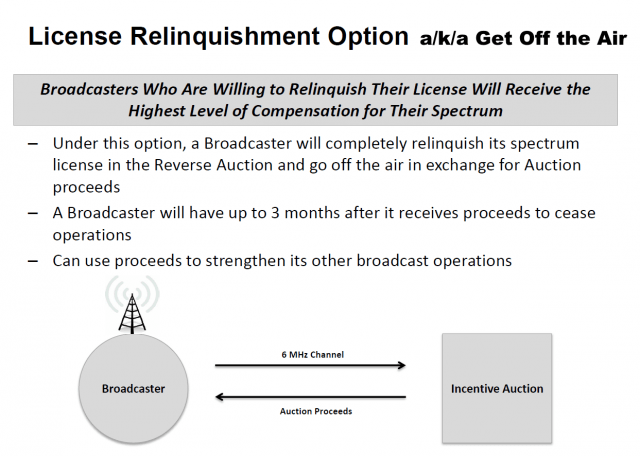

The Federal Communications Commission announced Friday it will  There is so much money to be made buying and selling the public airwaves — at least twice as much as broadcasters originally anticipated– spectrum speculators have also jumped on board, snapping up low power television station construction permits and existing stations with hopes of selling them off the air in return for millions in compensation. Wireless customers are effectively footing the bill for the auction as wireless companies bid for the additional spectrum. Television stations will receive 85% of the proceeds, the FCC will keep 15%.

There is so much money to be made buying and selling the public airwaves — at least twice as much as broadcasters originally anticipated– spectrum speculators have also jumped on board, snapping up low power television station construction permits and existing stations with hopes of selling them off the air in return for millions in compensation. Wireless customers are effectively footing the bill for the auction as wireless companies bid for the additional spectrum. Television stations will receive 85% of the proceeds, the FCC will keep 15%. Major network-affiliated or owned stations in major cities are unlikely to take the deal. But in medium and smaller-sized markets where conglomerates own and operate most television stations, there is a greater chance some will be closed down, moved to a lower channel, or transferred to a digital sub-channel of a co-owned-and-operated station in the same city. The most likely targets for shutdown will be independent, CW and MyNetworkTV affiliates. In smaller cities, multiple network affiliates owned by one company could be combined, relinquishing one or more channels in return for tens of millions in cash compensation.

Major network-affiliated or owned stations in major cities are unlikely to take the deal. But in medium and smaller-sized markets where conglomerates own and operate most television stations, there is a greater chance some will be closed down, moved to a lower channel, or transferred to a digital sub-channel of a co-owned-and-operated station in the same city. The most likely targets for shutdown will be independent, CW and MyNetworkTV affiliates. In smaller cities, multiple network affiliates owned by one company could be combined, relinquishing one or more channels in return for tens of millions in cash compensation. T-Mobile has asked the Federal Communications Commission to investigate AT&T’s “artificially high roaming rates” charged when its customers travel outside of T-Mobile’s home service area.

T-Mobile has asked the Federal Communications Commission to investigate AT&T’s “artificially high roaming rates” charged when its customers travel outside of T-Mobile’s home service area. Because of AT&T’s artificially high roaming rates, T-Mobile wireless customers roaming in South Africa have a better user experience than customers roaming on AT&T’s network in South Dakota, argues T-Mobile. Their speed is twice as fast, and their data usage is unlimited.

Because of AT&T’s artificially high roaming rates, T-Mobile wireless customers roaming in South Africa have a better user experience than customers roaming on AT&T’s network in South Dakota, argues T-Mobile. Their speed is twice as fast, and their data usage is unlimited.