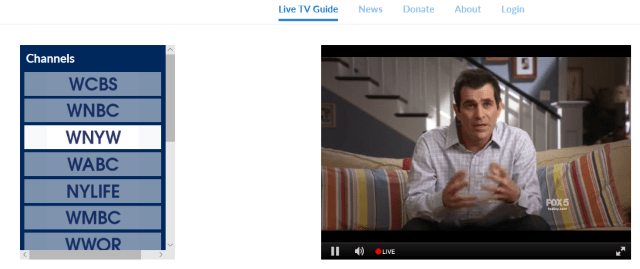

If you are a resident of New York City, you can now stream 15 over the air local television stations for free, at least until the station owners send their lawyers after the coalition running the new service.

If you are a resident of New York City, you can now stream 15 over the air local television stations for free, at least until the station owners send their lawyers after the coalition running the new service.

Locast.org is owned and operated by Sports Fan Coalition NY, a non-profit organization best known for successfully petitioning the Federal Communications Commission to eliminate the Sports Blackout Rule that forced local broadcast stations near stadiums to black out a game if a team did not sell a certain percentage of tickets by a certain time prior to the game.

The group launched Locast to challenge the idea that those unable to receive good reception of over-the-air local stations need to subscribe to a pay television provider to get a clear and reliable picture. Cord-cutters, in particular, often fear the loss of local television stations when they drop their cable subscription. Locast is designed to make sure those relying on streamed entertainment can also get free broadcast television over their internet connection.

The service currently provides 15 channels that broadcast in New York City:

- WABC (ABC)

- WCBS (CBS)

- WNBC (NBC)

- WNYW (FOX)

- WNET (PBS)

- WLIW (PBS)

- WWOR (MyNetworkTV)

- WPIX (CW)

- WPXN (Ion)

- WNJU (Telemundo)

- WFUT (UniMás)

- WMBC (Ind.)

- WLNY (Ind.)

- WFTY (Justice Network)

- WNYE (NYLIFE)

Viewers must live within the New York City television market to receive the service, and Locast enforces this with GPS and other similar location verification tools. Some residents of northern New Jersey complain they are unable to access the service, despite being within the New York City television market, a problem the group recognized and is attempting to fix. Viewers can watch the service on a desktop computer, mobile device, or tablet. There is no DVR service available at this time.

Stream quality is acceptable, but not stellar. In tests, we found the service suffered from occasional artifacts and was somewhat grainy. This would be particularly noticeable on a large screen television, much less so on portable devices. The picture was slightly better than Standard Definition. There were occasions when certain channels were unavailable and others suffered from streaming problems that caused portions of the audio or video to disappear. Remember, however, the service is new and free.

Locast offers a web-based interface.

The biggest challenge to Locast will not be the video quality of its streaming television channels. It will be dealing with lawyers.

Locast, like many similar services that came before it, relies on a novel interpretation of U.S. Copyright Law and the perceived loopholes it offers those who want to attempt to expand the definition of how consumers receive broadcast television signals. In this case, the service compares itself to a digital translator service similar to what some television stations use to distribute their signals to remote low-power translator stations that act as repeaters — providing better reception of stations that have trouble reaching parts of their local market.

Over the past two decades, several companies have tried and failed to offer independent online streams of television stations without the permission of station owners.

In 1999, iCraveTV provided more than a dozen Canadian and American television stations received over the air in Toronto made available to a nationwide online audience. The over-the-air stations (and the networks they affiliated with) in Buffalo, N.Y., promptly launched legal action against the company, challenging its claim it was entitled to offer the service because it was effectively a cable operator. International copyright law claims led to a preliminary injunction against the service and the threat of costly ongoing litigation convinced the owner of iCraveTV to stop the service in return for dropping lawsuits.

In 1999, iCraveTV provided more than a dozen Canadian and American television stations received over the air in Toronto made available to a nationwide online audience. The over-the-air stations (and the networks they affiliated with) in Buffalo, N.Y., promptly launched legal action against the company, challenging its claim it was entitled to offer the service because it was effectively a cable operator. International copyright law claims led to a preliminary injunction against the service and the threat of costly ongoing litigation convinced the owner of iCraveTV to stop the service in return for dropping lawsuits.

In 2011, ivi.tv streamed television signals from Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago until a judge signed an injunction forcing those stations off the paid service. Several court actions against FilmOn.com, a similar service operating around the same time, also stripped most of its TV station lineup off the service.

The highest profile attempt to avoid getting permission from TV station owners to stream their programming came in 2012 with the launch of Aereo, which sought to exploit a perceived loophole in what constituted reception of a TV station. Aereo assigned a tiny antenna for each customer to receive over the air stations, starting in the New York City area. Stations received by that antenna were delivered to subscribers over an internet video stream. The idea was that Aereo was not distributing one TV signal for multiple customers. It was merely extending the concept of an ‘antenna’ to include internet delivery of signals to those verifiably living within the New York City television market.

Broadcasters ran up large legal bills to defeat Aereo in two major court cases. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Aereo, claiming it breached copyright law. The service attempted one last effort to stay up and running, asking the U.S. Copyright Office for a copyright license after the Supreme Court seemed to call the service a “cable system.” Both the Copyright Office and a district court found Aereo was not entitled to a cable compulsory license and granted broadcasters a preliminary injunction that effectively put Aereo out of business.

Broadcasters ran up large legal bills to defeat Aereo in two major court cases. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against Aereo, claiming it breached copyright law. The service attempted one last effort to stay up and running, asking the U.S. Copyright Office for a copyright license after the Supreme Court seemed to call the service a “cable system.” Both the Copyright Office and a district court found Aereo was not entitled to a cable compulsory license and granted broadcasters a preliminary injunction that effectively put Aereo out of business.

All of these ventures attempted similar arguments that Locast is now using to justify why it should be allowed to distribute live streams of local television stations without the consent of station owners. The courts have traditionally bowed to the broadcasters and their allied lobbyists, television networks, and pay television providers that would feel threatened if a service like Locast gave away for free what they sell to consumers.

The Sports Fan Coalition’s legal justification comes from an exception Congress made to the copyright law’s insistence that permission from a station owner was required to redistribute their signal, unless one operated a cable system.

“Any ‘non-profit organization’ could make a ‘secondary transmission’ of a local broadcast signal, provided the non-profit did not receive any ‘direct or indirect commercial advantage’ and either offered the signal for free or for a fee ‘necessary to defray the actual and reasonable costs’ of providing the service. 17 U.S.C. 111(a)(5),” the group argues. “Sports Fans Coalition NY is a non-profit organization under the laws of New York State. Locast.org does not charge viewers for the digital translator service (although we do ask for contributions) and if it does so, will only recover costs as stipulated in the copyright statute. Finally, in dozens of pages of legal analysis provided to Sports Fans Coalition, an expert in copyright law concluded that under this particular provision of the copyright statute, secondary transmission may be made online, the same way traditional broadcast translators do so over the air.”

Traditionally, ‘secondary transmission’ has meant a building or complex owner receiving a station over the air from a rooftop antenna and providing it to tenants or residents over a Master Antenna TV coaxial cable connection (or similar technology). College campuses, hospitals, and other multi-dwelling unit owners often provide similar wired reception of over the air stations as well, to assure quality reception.

Translator stations that pick up and repeat a television station on an adjacent channel to offer better reception in difficult-to-reach viewing areas typically run with the full consent, or are owned by, the television station they rebroadcast.

Locast attempts to broaden the definition of ‘secondary transmission’ to include distribution over the internet through video streaming. Although their expert in copyright law believes this is permissible, there are multiple court cases where judges have ruled against these types of services when a broadcaster objects. Locast will likely face time in a courtroom arguing for its right to exist, something the venture readily admits is likely to happen.

A representative from Comcast worried that the BDAC’s work has been so polarized towards the telecom industry, excluded state and local officials will have every reason to resist the BDAC’s findings and recommendations and refuse to adopt them.

A representative from Comcast worried that the BDAC’s work has been so polarized towards the telecom industry, excluded state and local officials will have every reason to resist the BDAC’s findings and recommendations and refuse to adopt them.

Subscribe

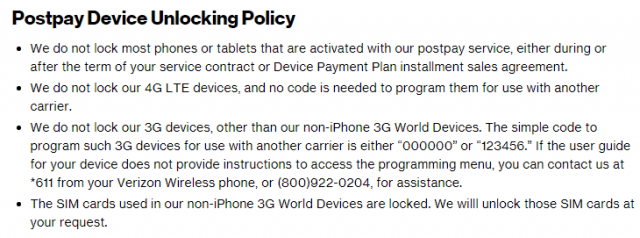

Subscribe Verizon Wireless, ignoring its agreement with the Federal Communications Commission not to lock handsets, will soon stop selling unlocked phones, at least temporarily preventing customers from taking their phones to another carrier or overseas without Verizon’s consent.

Verizon Wireless, ignoring its agreement with the Federal Communications Commission not to lock handsets, will soon stop selling unlocked phones, at least temporarily preventing customers from taking their phones to another carrier or overseas without Verizon’s consent.

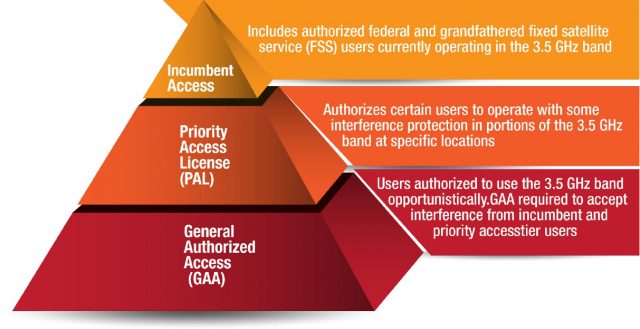

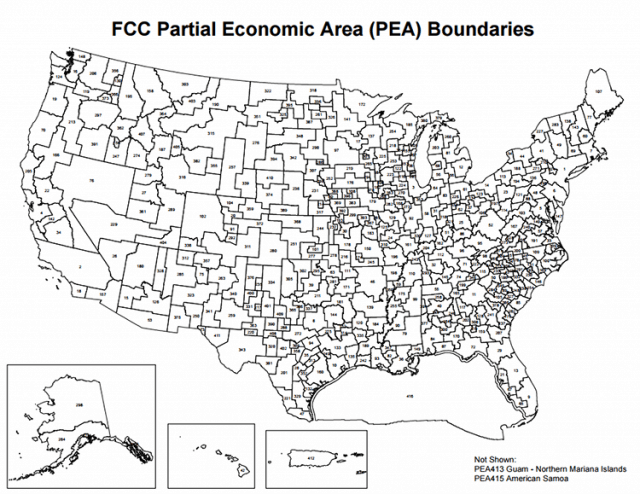

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

“When I called [the FCC] to check on the status of the BDAC selection process [earlier this year] and identified myself as an employee from the City of Santa Monica, the gentleman on the phone laughed hysterically,” Carter said. “At first I didn’t get the joke. When I saw the appointees for the municipal working group—only three out of 24 positions were from local government—I got the joke.”

“When I called [the FCC] to check on the status of the BDAC selection process [earlier this year] and identified myself as an employee from the City of Santa Monica, the gentleman on the phone laughed hysterically,” Carter said. “At first I didn’t get the joke. When I saw the appointees for the municipal working group—only three out of 24 positions were from local government—I got the joke.” CPI spoke with many local officials who asked to participate as a member of BDAC, but were turned down:

CPI spoke with many local officials who asked to participate as a member of BDAC, but were turned down: If you are a resident of New York City, you can now stream 15 over the air local television stations for free, at least until the station owners send their lawyers after the coalition running the new service.

If you are a resident of New York City, you can now stream 15 over the air local television stations for free, at least until the station owners send their lawyers after the coalition running the new service.

In 1999, iCraveTV provided more than a dozen Canadian and American television stations received over the air in Toronto made available to a nationwide online audience. The over-the-air stations (and the networks they affiliated with) in Buffalo, N.Y., promptly launched legal action against the company, challenging its claim it was entitled to offer the service because it was effectively a cable operator. International copyright law claims led to a preliminary injunction against the service and the threat of costly ongoing litigation convinced the owner of iCraveTV to stop the service in return for dropping lawsuits.

In 1999, iCraveTV provided more than a dozen Canadian and American television stations received over the air in Toronto made available to a nationwide online audience. The over-the-air stations (and the networks they affiliated with) in Buffalo, N.Y., promptly launched legal action against the company, challenging its claim it was entitled to offer the service because it was effectively a cable operator. International copyright law claims led to a preliminary injunction against the service and the threat of costly ongoing litigation convinced the owner of iCraveTV to stop the service in return for dropping lawsuits. Broadcasters ran up large legal bills to defeat Aereo in two major court cases. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court

Broadcasters ran up large legal bills to defeat Aereo in two major court cases. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court