Phillip “Section 706 is a road to nowhere” Dampier

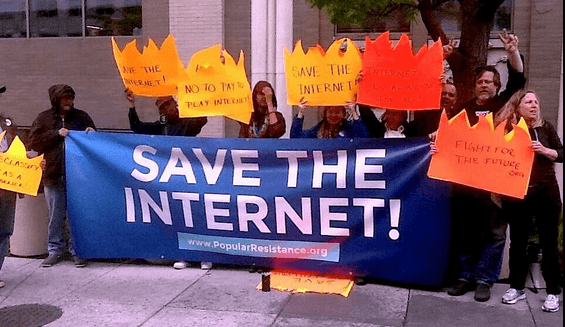

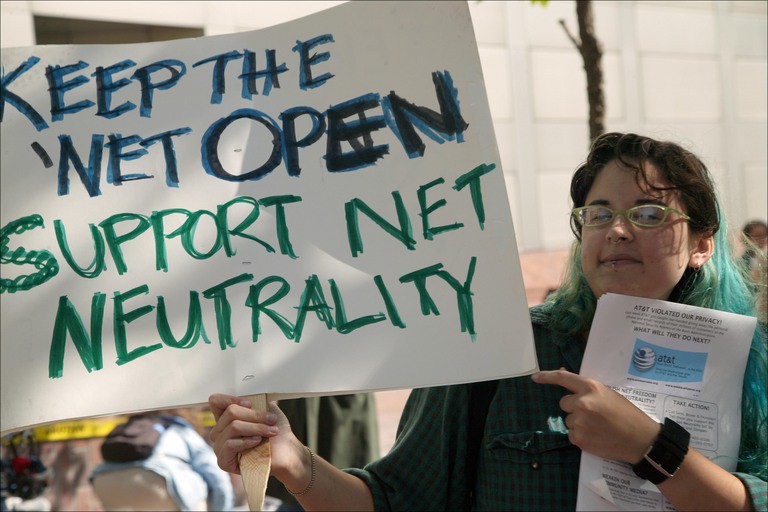

After thousands of consumers joined more than 100 Internet companies and two of five commissioners at the Federal Communications Commission to complain about Chairman Tom Wheeler’s vision of Net Neutrality, the head of the FCC claims he has revised his proposal to better enforce Internet traffic equality.

Last week, huge online companies like Amazon, eBay, and Facebook jointly called Wheeler’s ideas of Net Neutrality “a grave threat to the Internet.”

In response over the weekend, an official close to the chairman leaked word to the Wall Street Journal that Wheeler was changing his proposal. Despite that, a closer examination of Wheeler’s ideas continues to show his unwavering faith in providers voluntarily behaving themselves. Wheeler’s evolving definition of Net Neutrality is fine… if you live in OppositeLand. His proposal would allow Internet Service Providers and content companies to negotiate paid traffic prioritization agreements — the exact opposite of Net Neutrality — allowing certain Internet traffic to race to the front of the traffic line.

Such an idea is a non-starter among Net Neutrality advocates, precisely because it undermines a core principle of the Open Internet — discriminating for or against certain web traffic because of a paid arrangement creates an unfair playing field likely to harm Internet start-ups and other independent entities that can’t afford the “pay to play” prices ISPs may seek.

Paid traffic prioritization agreements only make business sense when a provider creates the network conditions that require their consideration. If a provider operated a robust network with plenty of capacity, there would be no incentive for such agreements because Internet traffic would have no trouble reaching customers with or without the agreement.

But as Netflix customers saw earlier this year, Comcast and several other cable operators are now in the bandwidth shortage business — unwilling to keep up investments in network upgrades required to allow paying customers to access the Internet content they want.

While there is some argument that the peering agreement between Comcast and Netflix is not a classic case of smashing Net Neutrality, the effect on customers is the same. If a provider refuses to upgrade connections to the Internet without financial compensation from content companies, the Internet slow lane for that content emerges. Message: Sign a paid contract for a better connection and your clogged content will suddenly arrive with ease.

Wheeler has ineffectively argued that his proposal to allow these kinds of paid arrangements do not inherently commercially segregate the Internet into fast and slow lanes.

Wheeler has ineffectively argued that his proposal to allow these kinds of paid arrangements do not inherently commercially segregate the Internet into fast and slow lanes.

But in fact it will, not by artificially throttling the speeds of deprioritized, non-paying content companies, but by consigning them to increasingly congested broadband pipes that only work in top form for prioritized, first class traffic.

With Wheeler’s philosophy “unchanged” according to the Journal, his defense of his revised Net Neutrality proposal continues to rely on non germane arguments.

For example, Wheeler claims he will make sure the FCC “scrutinizes deals to make sure that the broadband providers don’t unfairly put nonpaying companies’ content at a disadvantage.” But in Wheeler’s World of Net Neutrality, providers would have to blatantly and intentionally throttle traffic to cross the line.

“I won’t allow some companies to force Internet users into a slow lane so that others with special privileges can have superior service,” Mr. Wheeler wrote (emphasis ours) to Google and other companies.

But if your access to YouTube is slow because Google won’t pay Comcast for a direct connection with the cable company, it is doubtful Wheeler’s proposal would ever consider that a clear-cut case of Comcast “forcing” customers into a “slow lane.” After all, Comcast itself isn’t interfering with Netflix traffic, it just isn’t provisioning enough room on its network to accommodate customer demand.

Another side issue nobody has mentioned is usage cap discrimination. Comcast exempts certain traffic from the usage cap it is gradually reintroducing around the country. Its preferred partners can avoid usage-deterring caps while those not aligned with Comcast are left on the meter.

Wheeler

Some equipment manufacturers are producing even more sophisticated traffic management technology that could make it very difficult to identify fast and slow lanes, yet still opens the door to further monetization of Internet usage and performance in favor of a provider’s partners or against their competitors.

With Internet speeds and capacity gradually rising, the need for paid priority traffic agreements should decline, unless providers choose to cut back on upgrades to push another agenda. Already massively profitable, there is no excuse for providers not to incrementally upgrade their networks to meet customer demand. Prices for service have risen, even as the costs of providing the service have dropped overall.

Wheeler seems content to bend over backwards trying to shove a round Net Neutrality framework into a square regulatory black hole. Former chairman Julius Genachowski did the same, pretending that the FCC has oversight authority under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act. But in fact that section is dedicated to expanding broadband access with restricted regulatory powers:

The Commission and each State commission with regulatory jurisdiction over telecommunications services shall encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans (including, in particular, elementary and secondary schools and classrooms) by utilizing, in a manner consistent with the public interest, convenience, and necessity, price cap regulation, regulatory forbearance, measures that promote competition in the local telecommunications market, or other regulating methods that remove barriers to infrastructure investment.

The spirit of the 1996 Telecom Act was deregulation — that language pertaining to “regulatory forbearance” encourages regulators to restrain themselves from reflexively solving every problem with a new regulation. The words about “removing barriers to infrastructure investment” might as well be industry code language for the inevitable talking point: “deregulation removes barriers to investment.”

With a shaky foundation like that, any effort by the FCC to depend on Section 706 as its enabling authority to oversee the introduction of any significant broadband regulation is a house of cards.

With a shaky foundation like that, any effort by the FCC to depend on Section 706 as its enabling authority to oversee the introduction of any significant broadband regulation is a house of cards.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed. In the Verizon network management case, the court found that the FCC was not allowed to use Section 706 to issue broad regulations that contradicted another part of the Communications Act.

U.S.C. 153(51) was and remains the FCC’s Section 706-Achilles Heel and the judge kicked it. This section of the Act says “a telecommunications carrier shall be treated as a common carrier under this [Act] only to the extent that it is engaged in providing telecommunications services.”

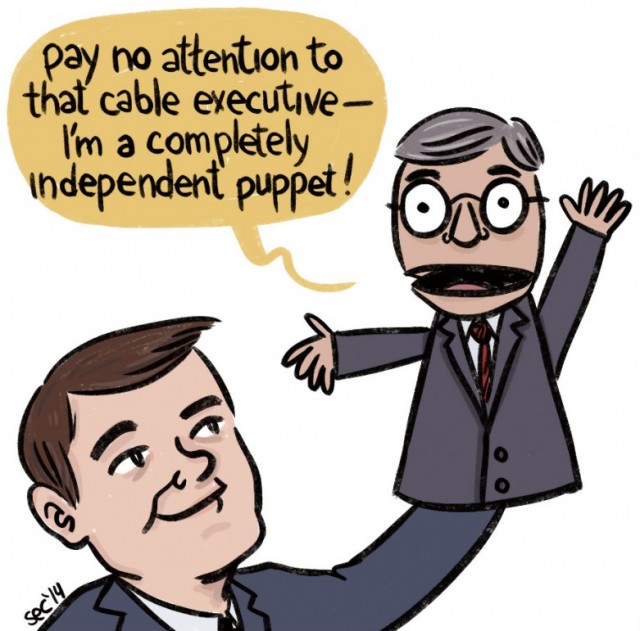

The current president of the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA) Michael Powell — coincidentally also former chairman of the FCC under President George W. Bush — helped see to it that broadband was not defined as a “telecommunications service.” Instead, it is considered an “information service” for regulatory purposes. This decision shielded emerging Internet providers (especially big phone and cable companies) from the kinds of traditional telecom utility regulations landline telephone companies lived with for decades. Of course, millions were also spent to lobby the telecom deregulation-friendly Clinton and Bush administrations with the idea to adopt “light touch” broadband regulatory policy. A Republican-dominated FCC had no trouble voluntarily limiting its own authority to oversee broadband by declaring both wired and wireless broadband providers “information services.”

Tom Wheeler is the former president of the National Cable & Telecommunications Association

So it was the FCC itself that caused this regulatory mess. But the Supreme Court provided a way out, by declaring it was within the FCC’s own discretion to decide how to regulate broadband, either under Title I as an information service or Title II as a telecommunications service. If the FCC declares broadband as a telecommunications service, the regulatory headaches largely disappear. The FCC has well-tested authority to impose common carrier regulations on providers, including Net Neutrality protections, under Title II.

In fact, the very definition of “common carrier” is tailor-made for Net Neutrality because it generally requires that all customers be offered service on a standardized and non-discriminatory basis, and may include a requirement that those services be priced reasonably.

Inexplicably, Chairman Wheeler last week announced his intention to keep ignoring the straight-line GPS-like directions from the court that would snatch the FCC’s attorneys from the jaws of defeat to victory and has recalculated another proposed trip over Section 706’s mysterious bumpy side streets and dirt roads. Assuming the FCC ever arrives at its destination, it is a sure bet it will be met by attorneys from AT&T, Comcast, or Verizon with yet more lawsuits claiming the FCC has violated their rights by exceeding their authority.

Wheeler also doesn’t mollify anyone with his commitment to set up yet another layer of FCC bureaucracy to protect Internet start-ups:

Mr. Wheeler’s updated draft would also propose a new ombudsman position with ‘significant enforcement authority’ to advocate on behalf of startups, according to one of the officials. The goal would be to ensure all parties have access to the FCC’s process for resolving disputes.

Anyone who has taken a dispute to the FCC knows how fun and exciting a process that is. But even worse than the legal expense and long delays, Wheeler’s excessively ambiguous definitions of what constitutes fair paid prioritization and slow and fast lanes is money in the bank for regulatory litigators that will sue when a company doesn’t get the resolution it wants.

Wheeler promises the revised proceeding will invite more comments from the public regarding whether paid prioritization is a good idea and whether Title II reclassification is the better option. While we appreciate the fact Wheeler is asking the questions, we’ve been too often disappointed by FCC chairmen that apply prioritization of a different sort — to those that routinely have business before the FCC, including phone and cable company executives. Chairman Genachowski’s Net Neutrality policy was largely drafted behind closed doors by FCC lawyers and telecom industry lobbyists. Consumers were not invited and we’re not certain the FCC is actually listening to us.

The Wall Street Journal indicates the road remains bumpy and pitted with potholes:

Mr. Wheeler’s insistence that his strategy would preserve an open Internet, without previously offering much insight into how, has been a source of disquiet within his agency. Of the five-member commission, both Republicans are against any form of net neutrality rules, which they view as unnecessary. Commission observers will be watching the reaction of the two Democrats, Ms. Rosenworcel and Mignon Clyburn, to Mr. Wheeler’s new language.

“There is a wide feeling on the eighth floor that this is a debacle and I think people would like to see a change of course,” said another FCC official. “We may not agree on the course, but we agree the road we’re on is to disaster.”

There is still time to recalculate, but we wonder if Mr. Wheeler, a longtime former lobbyist for the wireless and cable industries, is capable of sufficiently bending towards the public interest.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Smit also promised major broadband speed upgrades and other improvements for Time Warner Cable customers, but nobody mentioned Comcast’s gradual reintroduction of usage caps on residential broadband accounts.

Smit also promised major broadband speed upgrades and other improvements for Time Warner Cable customers, but nobody mentioned Comcast’s gradual reintroduction of usage caps on residential broadband accounts.

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.