As part of the Federal Communications Commission’s release of final Net Neutrality regulations, the FCC included this “Fact/Fiction” news release intending to debunk industry (and political) opposition to Net Neutrality.

The Open Internet Order: Preserving and Protecting the Internet for All Americans

The Open Internet Order: Preserving and Protecting the Internet for All Americans

The Commission has released the full and final text of the Open Internet Order, which will preserve and protect the Internet as a platform for innovation, expression and economic growth. An Open Internet means consumers can go where they want, when they want. It means innovators can develop products and services without asking for permission. It means consumers will demand more and better broadband as they enjoy new Internet services, applications and content.

Protecting Consumers, Providing Certainty for Innovators and Investors

Before the Commission adopted this Order, there were no rules preventing broadband providers from conduct that would threaten the Open Internet. This Order implements bright line rules to ban blocking, throttling and paid prioritization (or “fast lanes”) and, for the first time, the rules fully apply to mobile.

Open Internet rules are grounded in the strongest possible legal foundation by relying on multiple sources of authority, including Title II of the Communications Act and Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. However, as part of this Order, the Commission refrains (or “forbears”) from enforcing provisions of Title II that are not relevant to modern broadband service. Together, Title II and Section 706 support clear rules of the road, providing the certainty needed by innovators and investors, and the competitive choices and freedom demanded by consumers.

Separating Fact from Fiction

The Order uses every tool in the Commission’s toolbox to make sure the Internet stays fair, fast and open for all Americans, while ensuring investment and innovation can flourish. We encourage the public to read the Order, which reflects the input of millions of Americans and allows everyone to separate myths from fact, such as:

Myth: This is utility-style regulation.

Fact: The Order takes a modernized approach to Title II, tailored for the 21st Century

There is no “utility-style” regulation. The Order bars the kinds of tariffing, rate regulation, unbundling requirements and administrative burdens that are the hallmarks of traditional utility regulation. No broadband provider will need to get the FCC’s approval before offering any price, product or plan. (paragraphs 37-38, 417, 451-452, 497-505)

Myth: The FCC plans to set broadband rates and regulate retail prices in response to consumer complaints.

Fact: The Order doesn’t regulate retail broadband rates.

Old-style telephone regulation required companies to file tariffs with the FCC and await regulatory review before they could bring new products to markets – such an approval process does not exist and is not permitted under this Order. Broadband providers will be able to adjust retail rates without Commission approval and without having to wait even a minute. (paragraphs 37, 451-452, 497-505)

Much has been made of the Section 201(b) authority in Title II under which the Commission may hear complaints and respond to conduct that violates our Open Internet rules. The claim is made that it will be a back-door form of rate regulation. This exact same authority has existed for wireless voice service since 1993 and has never produced rate regulation. (paragraphs 38, 409-410, 421-423)

Myth: This will increase consumers’ broadband bills and/or raise taxes.

Fact: The Order doesn’t impose new taxes or fees or otherwise increase prices.

Nothing in the Order imposes or authorizes new taxes or fees. In fact, the Internet Tax Freedom Act currently bans state and local taxes on broadband access regardless of how the FCC classifies it. With respect to Universal Service, the Order does not impose mandatory contribution assessments, but simply allows a current, separate proceeding on how to reform universal service contributions to proceed. (paragraphs 37, 57-58, 430-433, 488-491)

Myth: This is a plan to regulate the Internet and let the government take over the Internet.

Fact: The Order doesn’t regulate Internet content, applications or services or how the Internet operates, its routing or its addressing.

The Order does not regulate the Internet. It applies to broadband providers – the companies that connect people’s homes to the public Internet. In other words, the Order protects consumers’ and innovators’ “last-mile” access to what’s on the Internet—the applications, content or services that ride on it and the devices that attach to it. It means consumers can go where they want, when they want and it means innovators can develop products and services without asking for permission. (paragraphs 25-26, 186-193,336-340,382)

Myth: This proposal means the FCC will get to decide which service plan you can choose.

Fact: The Order doesn’t limit consumers’ choices or ban broadband data plans.

There is no approval requirement before retail plans, prices or services can be offered to consumers. Broadband providers will continue to be able to offer new competitive services and rates. This means that when a broadband provider wants to add a faster tier of service at a new price, for instance, it is free to do so. Similarly, a broadband provider is free to change pricing without approval. What providers can’t do is engage in behavior that threatens the Open Internet. (paragraphs 139, 144, 151-153)

Myth: This will embolden authoritarian states to tighten their grip on the Internet.

Fact: The Open Internet rules ensure the Internet continues to be a powerful platform for free expression, innovation and economic growth.

This Order does not regulate the operation of the Internet nor does it endorse governmental control of the way people use the Internet. This Order is a strong statement that no one – government or corporation – should interfere with the user’s right of free and open access to the Internet. In order to encourage other governments to establish policies to protect the free exchange of ideas on an open, unrestricted Internet, we must first protect those values at home. (paragraphs 76-77)

Myth: This will stifle innovation in new areas of Internet connectivity like connected cars or tele-health.

Fact: The Order doesn’t regulate the class of IP-based services that do not connect to the public Internet.

The Order does not regulate data services that do not go over the public Internet —sometimes called “specialized services” or “managed services” and described in the Order as “non-BIAS (Broadband Internet Access Service) services”. Consumers who buy these services don’t get, and don’t expect to get, access to all points on the Internet. Examples can include: VoIP from a cable system, VoLTE from a mobile operator, a dedicated heart-monitoring service, e-readers, connected cars, and other innovative data services we cannot imagine today. (paragraphs 35, 207-213)

Myth: This will lead to slower broadband speeds and reduced investment in broadband deployment.

Fact: The Order doesn’t reduce broadband investment or slow broadband speeds.

More openness leads to more consumer demand for more and better broadband. It’s that simple. No price regulation means consumer revenues for ISPs should be the same the day after the Order takes effect as they were the day before. It is these revenues that provide the stimulus for investment. History proves that investment will not be affected. For instance, in addition to the $270 billion invested in wireless voice service in the years in which it was the prime driver of mobile traffic (through 2009), wireline DSL was regulated as a common-carrier service until 2005—including a period in the late ‘90s and early 2000’s that saw the highest levels of wireline broadband infrastructure investment ever. (paragraphs 39, 412-414, 421-425)

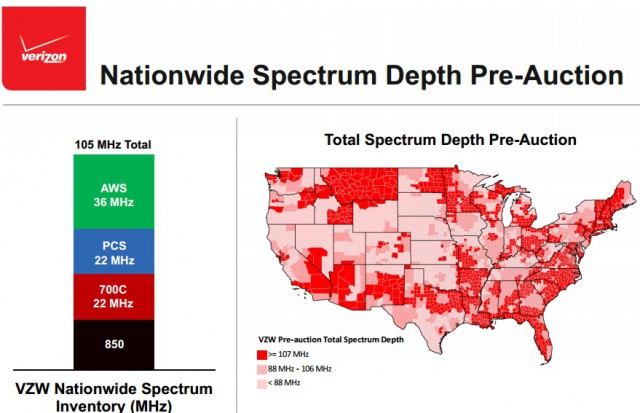

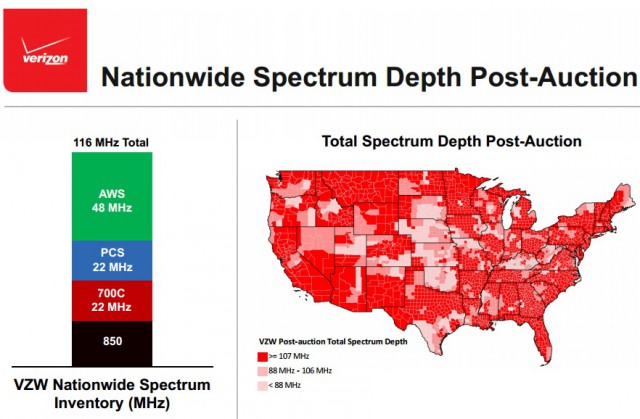

More recently, Verizon spent $4.74 billion in 2008 for licenses to C-block spectrum governed by FCC open access regulations and since then has invested tens of billions of dollars deploying mobile services. And just this year, Sprint, T-Mobile, Google Fiber, Frontier Communications, COMPTEL and NTCA—The Rural Broadband Association have all said that applying Title II to broadband services won’t harm investment. Finally, the recent AWS auction, conducted under the prospect of Title II regulation, generated bids (net of bidding credits) of more than $41 billion—further demonstrating that robust investment is not inconsistent with a modern, light-touch Title II regime. (paragraphs 339-40, 416, 423)

Myth: The new transparency rules add up to a new form of regulation.

Fact: Clear disclosure requirements benefit both consumers and industry.

The enhanced transparency requirements, which build on the existing transparency rule, will do a better job of ensuring that consumers know the price and performance of their Internet connections. They also benefit broadband providers and Internet content, application, and service providers by removing unnecessary uncertainties that affect the quality of their services. That’s not regulation, that’s efficient common-sense consumer protection. (paragraphs 23-24, 154-185)

Myth: The general conduct standard will chill innovation.

Fact: This is not new ground. The Commission also adopted a general conduct standard in 2010 and investment flourished.

There has always been a “just and reasonable” standard for telecommunications services – and investment has flourished. Since 2005, the Commission has made plain its intent to take action to preserve the Open Internet – and broadband services and investment have continued grow. Of specific significance, the 2010 Open Internet Order applied such a general conduct standard that was in force until 2014. In the three years that the 2010 Open Internet rules were in effect, broadband capital expenditures increased from $64 billion in 2009 to $75 billion in 2013. The standard adopted in the Order is tailored to the open Internet harms the Commission has identified. It focuses on whether the broadband provider is using its gatekeeper status in ways that unreasonably affect consumers’ and edge providers’ ability to use the Internet to communicate with each other. (paragraphs 2-4, 20-22, 133-153)

Subscribe

Subscribe

Time Warner (Entertainment): Not affiliated with Time Warner Cable, owning Time Warner (Entertainment) would gain Comcast important cable networks like TNT, HBO, and the Warner Bros. studio.

Time Warner (Entertainment): Not affiliated with Time Warner Cable, owning Time Warner (Entertainment) would gain Comcast important cable networks like TNT, HBO, and the Warner Bros. studio.