Four of the nation’s largest phone companies — two former Baby Bells, two independents — have very different ideas about solving the rural broadband problem in the country. Which company serves your area could make all the difference between having basic DSL service or nothing at all.

Some blame Wall Street for the problem, others criticize the leadership at companies that only see dollars, not solutions. Some attack the federal government for interfering in the natural order of the private market, and some even hold rural residents at fault for expecting too much while choosing to live out in the country.

This four-part series will examine the attitudes of the four largest phone companies you may be doing business with in your small town.

Today: CenturyLink — Our Commercial Customers Deliver 60% of Our Revenue; Our Attention Follows Accordingly

Today: CenturyLink — Our Commercial Customers Deliver 60% of Our Revenue; Our Attention Follows Accordingly

“Business customers now drive about 60% of our total operating revenues,” CenturyLink CEO Glenn F. Post III told investors in March. “Our focus on delivering advanced solutions and data hosting services to businesses are key factors in improving our top line revenue trend.”

With residential customers departing traditional landlines at an average rate of 5-10 percent a year, keeping customers has become an important priority for a number of phone companies, especially those who have plowed millions into mergers and acquisitions to build their businesses. For the past several years, CenturyLink has been acquiring small, regional independent phone companies, a former Baby Bell, and a competing landline provider Sprint used to think would be an important part of its business.

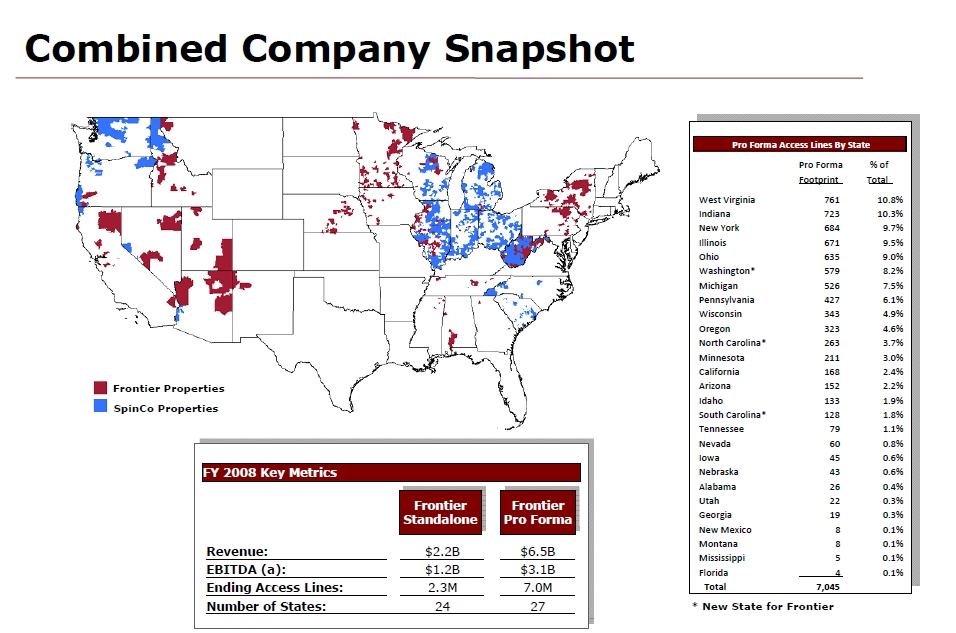

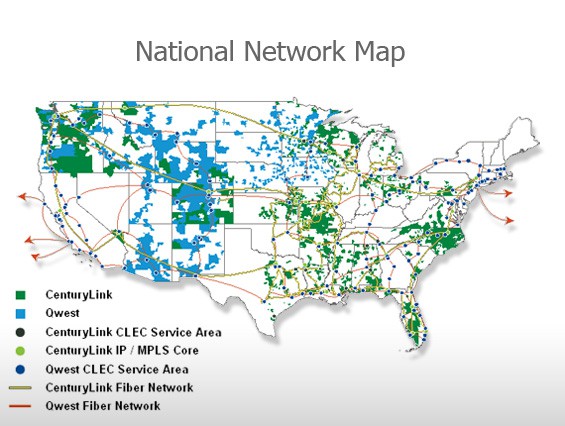

Century Telephone’s original customers were mostly cobbled together from acquisitions from other phone companies, including names like GTE, Central Telephone Company of Ohio (part of Centel), Pacific Telecom, Mebtel and GulfTel. But the biggest expansion of the company would come from acquisitions of Sprint-spinoff Embarq and former Baby Bell Qwest.

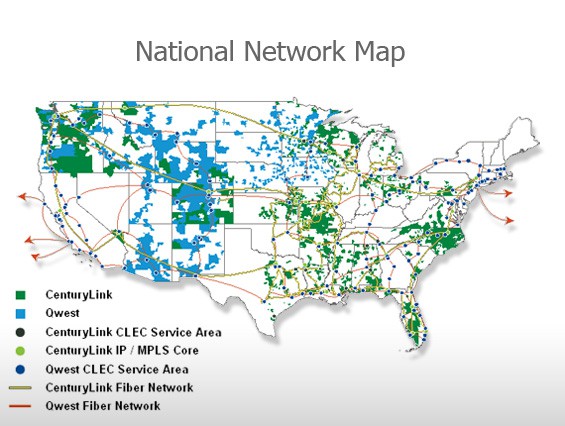

Today CenturyLink operates one of the nation’s largest independent phone companies, and serves markets large (primarily on the west coast) and small (rural communities primarily in the southeast, Missouri, Ohio, Indiana and Wisconsin).

CenturyLink’s revenues have often been uneven, mostly because of its acquisitions, landline losses, and the effects from competition in its larger markets. While CenturyLink’s acquisitions grew the company, they also saddled it with landline networks that have proved inadequate to meet the growing needs of customers. With a disconnect rate running between 6.4% this quarter and 7.6% in the same quarter a year ago, residential customers are leaving their voice lines behind in favor of cell phones and broadband customers are departing for faster speeds available from cable operators.

These “legacy services” lost the company $124 million in revenue — an 8.1% decrease over the past quarter. As customers depart, so do CenturyLink employees that used to handle the old landline network.

To make up the lost revenue, CenturyLink has gotten more aggressive in other areas of its business:

- Increasing focus on business/commercial and governmental services, including managed hosting, cloud computing and other commercially-targeted broadband initiatives;

- Deployment of fiber to cell towers as a growing revenue source;

- Limited, but ongoing rural broadband expansion;

- Development of Prism TV — a fiber to the neighborhood service targeting residential customers.

CenturyLink calls these their four key initiatives towards revenue stability, stable cash flow, and growth.

In the business services segment, CenturyLink sees enormous revenue potential selling businesses access to data centers, co-location services, and ethernet-speed broadband. Last year, CenturyLink acquired Savvis, an important enterprise-level service provider and owner of 50 data centers. Phone companies like CenturyLink are also in a race with large cable operators to be the first to offer cell phone companies access to “fiber-to-the-tower” service to support exploding data growth on 4G wireless networks.

Faster DSL, Fiber to the Neighborhood-Broadband Key to Keeping Residential Customers Happy

CenturyLink’s network map showing both its own service areas, and infrastructure obtained from the acquisition of Qwest.

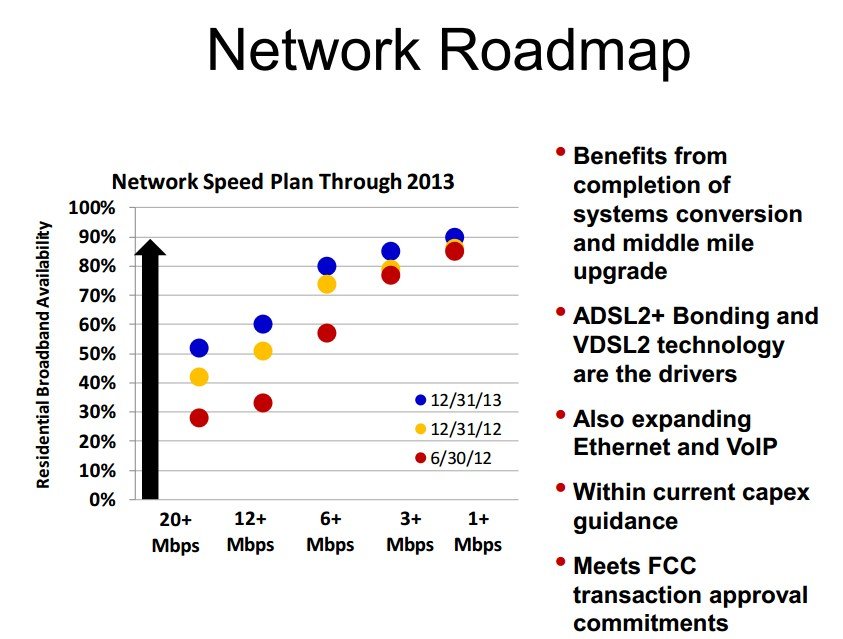

For consumers, CenturyLink has been moderately aggressive in some areas boosting speeds of its DSL services. The company claims 70% of their DSL-capable landline network provides speeds of at least 6Mbps. At least 55% supports 10Mbps or higher; over 25% can manage 20Mbps or faster.

The company’s Prism TV service, a fiber to the neighborhood upgrade comparable to AT&T U-verse, is now available to nearly 6.3 million homes and apartments in eight cities. By year end, CenturyLink says it will increase that to 7.1 million homes.

Prism represents a significant portion of CenturyLink’s investment in its residential business. So far, the results have not proven a major threat to the competition. CenturyLink added 15,000 Prism subscribers in the first quarter, but the company only has 8% of the market. Cable and satellite providers continue to dominate. But the company says Prism is helping to keep the customers they already have.

CenturyLink says it now taking Prism TV west into former Qwest territory, starting in and around Colorado Springs, Col.

Customers will likely be offered 130 channels starting at $59.99 a month with a free set top box (new customers typically receive a $20 monthly discount for the first six months of service).

The phone company will compete with Comcast, which sells 80 channels for $56 a month (new customers get a $26/mo discount for the first six months).

With CenturyLink providing a better deal, at least for television service, Colorado City officials hope the competition will bring down rates, at least for new customers. That may be exactly what happens, predicts Mark Ewell, a senior account executive with Windstream Communications.

“We could see some pressure on Comcast’s rates. I would like to see Comcast adopt a price model that doesn’t go up after a promotional period,” Ewell told The Gazette.

“CenturyLink is likely to be more of a threat to the satellite providers like DirecTV and Dish because they have a much higher market share in Colorado Springs than they do in most other markets because so many customers left Adelphia [acquired in bankruptcy by Comcast] when it had its financial problems. Those customers have already shown a willingness to leave the cable television provider and try another service.”

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/CenturyLink Prism TV.flv[/flv]

CenturyLink shows off its new Prism TV offering in this company-produced video. (2 minutes)

CenturyTel acquires Embarq and changes its name to CenturyLink to reduce the emphasis on its traditional landline business.

CenturyLink’s arrival in the triple-play business of phone, Internet, and television service could be the first serious competition Comcast has gotten outside of satellite providers. WideOpenWest had a franchise to provide service in 2000 but never did. Falcon Broadband won a franchise in 2006, but only provides service to around 1,500 customers in the Banning Lewis Ranch, Black Forest, and Falcon areas. Porchlight Communications received a franchise in 2007, installed service for 500 customers but ultimately never charged them. Porchlight’s IPTV service never worked properly with its chosen set top boxes. That fatal flaw put the company out of the cable business, and the company turned the porch light off for good, abandoning its franchise.

Rural Broadband: Unless the Government Delivers More Subsidies, Rural Customers Will Continue Waiting

In late July, CenturyLink announced it would accept $35 million from the Federal Communications Commission’s new Connect America Program (CAP) to deploy broadband to homes and businesses in rural, broadband-deprived parts of its service area.

CenturyLink has the capability to extend broadband to 100 percent of its customers, but not the willingness to invest the money to make that happen, critics contend. CenturyLink freely admits it applies a financial test when considering when and where to expand its DSL broadband service into its most rural service areas.

In short, the company must recoup its costs of deploying broadband within a certain time frame, and be confident that a certain percentage of customers are going to sign up for broadband service, before it will agree to make the investment. Virtually all of CenturyLink’s current service areas have already met or failed that test, which leaves an indefinite group of broadband “have’s” and “have-nots.”

To shake up the status quo, the FCC proposed to shift Universal Service Fund money, collected from all phone customers, away from landline service towards rural broadband deployment. This invites CenturyLink, and other phone companies, to run those financial tests again. With urban customers footing part of the bill, theoretically more homes should squeak past the return on investment test.

To shake up the status quo, the FCC proposed to shift Universal Service Fund money, collected from all phone customers, away from landline service towards rural broadband deployment. This invites CenturyLink, and other phone companies, to run those financial tests again. With urban customers footing part of the bill, theoretically more homes should squeak past the return on investment test.

In fact, more homes will finally get CenturyLink broadband — around 45,000 in semi-rural and suburban areas where the costs to provide the service are not as great as in truly rural areas. The FCC is offering to cover just short of $800 per household to cut the costs of deploying rural Internet access.

But CenturyLink complains the money is not nearly enough to solve the really-rural broadband problem.

“In very rural areas where we really have the greatest need for support, this amount, on a per-location basis, will not be enough to allow us to really do an economic build-out,” Post told investors this spring. “So we’re still in the process really of evaluating our opportunities….”

That will leave CenturyLink likely spending considerably more upgrading its urban landline network to support Prism TV instead of supplying rural broadband service.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/CenturyLink History.flv[/flv]

Jeff Oberschelp, vice president and general manager of CenturyLink of Nevada discusses the past history of CenturyLink and where phone companies are going in the future in this company-friendly interview. (6 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe