Did you realize if you are pro-Net Neutrality, you’re probably pro-piracy and a broadband hog? That’s the new low achieved this past week by Net Neutrality opponents who are spending millions trying to protect their broadband fiefdoms from any regulation. But even if they lose their fight to stop Net Neutrality when they find consumers won’t accept a throttled “network managed” broadband future, providers will be “forced” to control those dirty pirates and broadband hogs with usage limits and overlimit fees to help “pay for network expansion.”

It’s why Net Neutrality and Internet Overcharging schemes like usage caps and “consumption billing” go hand in hand. What providers can’t profit from on one end they’ll try from another.

Longtime readers of Stop the Cap! already know how this scam works. Canadian broadband users got stuck with both: speed throttles -and- usage caps and overlimit fees. Assuming purposely throttled speeds are banned by Net Neutrality policies, simply under-investing in network expansion, despite the rampant profit-earning capacity broadband delivers, gets us to the same place — throttled speeds from overcongested networks and a convenient excuse to impose usage limits and other control measures to more “fairly” provide service to every customer. Best of all, providers can pocket the overlimit fees charged to customers who exceed their allowance and train them to use less broadband with fears of more stinging penalty fees on their next bill.

Back in 2008, when Stop the Cap! launched, we challenged providers to provide the raw data to prove their assertions that they needed to impose formal limits and so-called “consumption-based billing” and abandon the lucrative flat rate pricing model that earns them billions in profits every year. Of course, they have always refused, citing “competitive reasons,” “customer privacy,” or some combination of laws that supposedly prohibits any third party analysis. Of course, they’re only too happy to characterize usage themselves, and we’re supposed to trust them — the same people that want to use that data to justify Internet Overcharging schemes. Independent analysis? When broadband pigs fly!

Now, telecom analyst Benoit Felten from the Yankee Group is asking the same questions on his Fiberevolution blog and issuing a challenge:

So here’s a challenge for them: in the next few days, I will specify on this blog a standard dataset that would enable me to do an in-depth data analysis into network usage by individual users. Any telco willing to actually understand what’s happening there and to answer the question on the existence of hogs once and for all can extract that data and send it over to me, I will analyse it for free, on my spare time. All I ask is that they let me publish the results of said research (even though their names need not be mentioned if they don’t wish it to be). Of course, if I find myself to be wrong and if indeed I manage to identify users that systematically degrade the experience for other users, I will say so publicly. If, as I suspect, there are no such users, I will also say so publicly. The data will back either of these assertions.

Felton’s co-author Herman offers his assessment:

Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, the way that telcos identify the Bandwidth Hogs is not by monitoring if they cause unfair traffic congestion for other users. No, they just measure the total data downloaded per user, list the top 5% and call them hogs.

For those service providers with data caps, these are usually set around 50 Gbyte and go up to 150 Gbyte a month. This is therefore a good indication of the level of bandwidth at which you start being considered a “hog”. But wait: 50 Gbyte a month is… 150 kbps average (0,15 Mbps), 150 Gbyte a month is 450 kbps on average. If you have a 10 Mbps link, that’s only 1,5 % or 4,5 % of its maximum advertised speed!

And that would be “hogging”?

The fact is that what most telcos call hogs are simply people who overall and on average download more than others. Blaming them for network congestion is actually an admission that telcos are uncomfortable with the ‘all you can eat’ broadband schemes that they themselves introduced on the market to get people to subscribe. In other words, the marketing push to get people to subscribe to broadband worked, but now the telcos see a missed opportunity at price discrimination…

TCP/IP is by definition an egalitarian protocol. Implemented well, it should result in an equal distribution of available bandwidth in the operator’s network between end-users; so the concept of a bandwidth hog is by definition an impossibility. An end-user can download all his access line will sustain when the network is comparatively empty, but as soon as it fills up from other users’ traffic, his own download (or upload) rate will diminish until it’s no bigger than what anyone else gets.

Rep. Eric Massa (D-NY) has a better idea to stop Internet Overcharging: the Broadband Internet Fairness Act (HR 2902), which would ban unjustified billing schemes for broadband

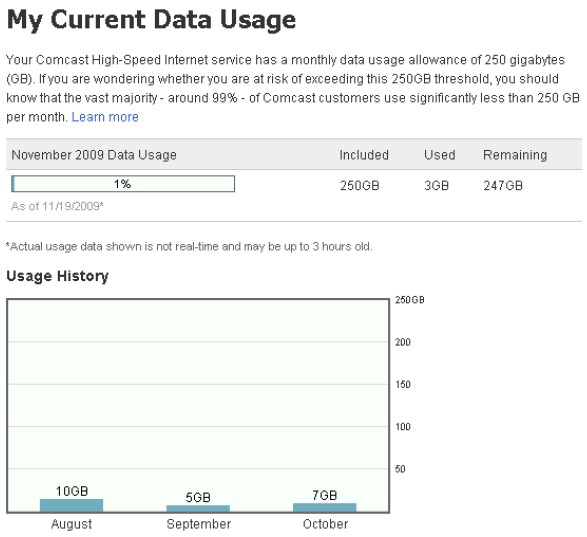

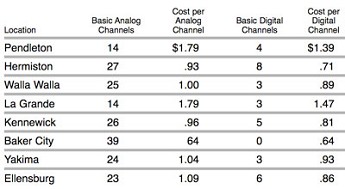

The arbitrary nature of what constitutes a “hog” invalidates providers’ arguments at the outset. Frontier defines a hog as someone who consumes more than 5GB. Comcast sets their definition of a broadband piggy at 250GB. The gap between the two is wide enough to allow a small planet to slip through unencumbered.

If a consumer does all of their downloading from midnight to six the following morning, are they as much of a hog on a shared cable modem network as the user watching Hulu during prime broadband usage time? Probably not. If a cable provider tries to force too many homes to share the same finite amount of bandwidth available in a designated area, service will slow for everyone during peak usage times. But nobody will notice or care if customers are maxing out their connection in the middle of the night. The appropriate answer, especially for an industry that enjoys enormous profits, is to expand their network to maintain basic quality of service at peak times. DOCSIS 3 upgrades for cable are cost efficient, flexible and often profitable, because providers can market new, premium-priced speed tiers to those who want cutting edge service.

Instead, some providers see delaying upgrades as a better answer, enjoying the cost savings that follow implementation of usage caps, limits and other overcharging schemes which artificially limit demand and further monetize their broadband service offerings.

Unfortunately, even if Felten got responses from providers, he’ll be forced to trust the integrity of data he didn’t collect himself. Rep. Eric Massa has a better idea. His proposed Broadband Internet Fairness Act would ban such overcharging schemes unless providers could prove to the satisfaction of a federal agency that such pricing was warranted. The big difference is that providing “massaged” data to Mr. Felton might be naughty, but would be downright criminal if tried with the federal government.

Shouldn’t the central lesson here be to “trust but verify?”

Subscribe

Subscribe