While wireless providers currently treat Wi-Fi as a friendly way to offload wireless data traffic from their 3G and 4G networks, the wireless industry is starting to ponder whether they can also earn additional profits from regulating your use of it.

While wireless providers currently treat Wi-Fi as a friendly way to offload wireless data traffic from their 3G and 4G networks, the wireless industry is starting to ponder whether they can also earn additional profits from regulating your use of it.

Dean Bubley has written a white paper for the wireless industry exploring Wi-Fi use by smartphone owners, and ways the industry can potentially cash in on it.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that Wi-Fi access will be a strategic part of mobile operators’ future network plans,” Bubley writes. “There are multiple use cases, ranging from offloading congested cells, through to reducing overseas roaming costs and innovative in-venue services.”

Bubley’s paper explores the recent history of some cell phone providers aggressively trying to offload traffic from their congested 3G networks to more-grounded Wi-Fi networks.

Among the most intent:

- AT&T, which acquired Wayport, a major Wireless ISP, and is placing Wi-Fi hotspots at various venues and in high traffic tourist areas in major cities and wants to seamlessly switch Apple iPhone users to Wi-Fi, where available, whenever possible;

- PCCW in Hong Kong;

- KT in the Republic of Korea, which has moved as much as 67 percent of its data traffic to Wi-Fi;

- KDDI in Japan, which is planning to deploy as many as 100,000 Wi-Fi Hotspots across the country.

America's most aggressive data offloader is pushing more and more customers to using their Wi-Fi Hotspots.

Bubley says the congestion some carriers experience isn’t necessarily from users downloading too much or watching too many online shows. Instead, it comes from “signalling congestion,” caused when a smartphone’s applications demand repeated attention from the carrier’s network. An application that requires regular, but short IP traffic connections, can pose a bigger problem than a user simply downloading a file. Moving this traffic to Wi-Fi can be a real resource-saver for wireless carriers.

Bubley notes many wireless companies would like to charge third-party developers fees to allow them access to each provider’s “app store.” Applications that consume a lot of resources could be charged more by providers (or banned altogether), while those that “behave well” could theoretically be charged a lower fee. The only thing preventing this type of a “two-sided business model,” charging both developers and consumers for the applications that work on smartphones, are Net Neutrality policies (or the threat of them) in many countries.

Instead, Bubley suggests, carriers should be more open and helpful with third party developers to assist them in developing more efficient applications on a voluntary basis.

Bubley also ponders future business strategies for Wi-Fi. He explores the next generation of Wi-Fi networks that allow users to establish automatic connections to the best possible signal without ponderous log-in screens, and new clients that can intelligently search out and connect to approved networks without user intervention. That means data traffic could theoretically be shifted to any authenticated or preferred Wi-Fi network without users having to mess with the phone’s settings. At the same time, that same technology could be used to keep customers off of free, third party Wi-Fi networks, in favor of networks operators run themselves.

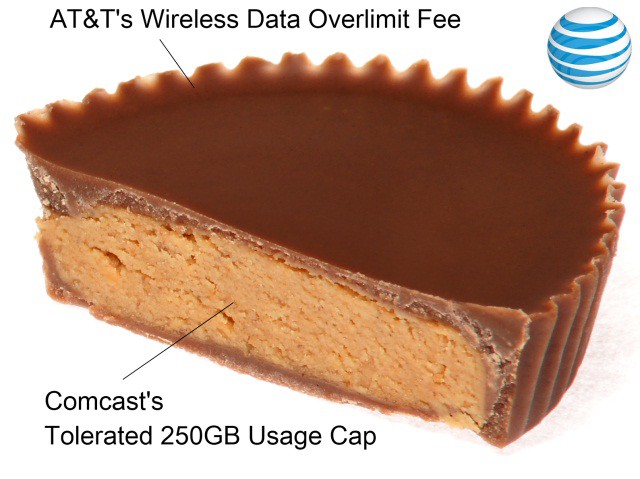

Policy controls are a major focus of Bubley’s paper. While he advocates for customer-friendly use of such controls, sophisticated network management tools can also be used to make a fortune for wireless providers who want to nickle and dime customers to death with usage fees, or open up new markets pitching Wi-Fi networks to new customers.

For example, a wireless carrier could sell a retail store ready-to-run Wi-Fi that pushes customers to a well-controlled, store-run network while customers shop — a network that forbids access to competitors or online merchants, in an effort to curtail browsing for items while comparing prices (or worse ordering) online from a competitor.

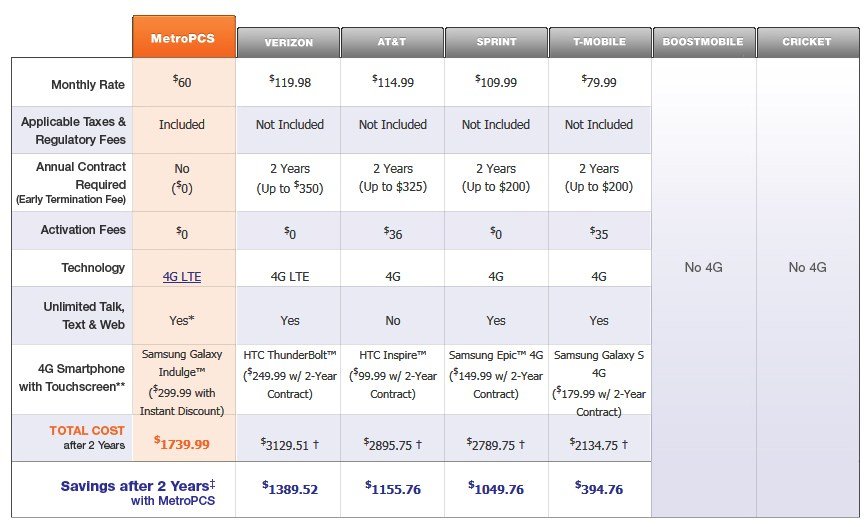

Customers could also face smartphones programmed to connect automatically to a Wi-Fi network, while excluding access to others while a “preferred” network is in range. Wireless carriers could develop the same Internet Overcharging schemes for Wi-Fi use that they have rolled out for 3G and 4G wireless network access. Also available: speed throttles for “non-preferred” applications, speed controls for less-valued ‘heavy users,’ and establishment of extra-fee “roaming charges” for using a non-preferred Wi-Fi network.

Bubley warns carriers not to go too far.

“[We] believe that operators need to internalize the concept of ‘WiFiNeutrality’ – actively blocking or impeding the user’s choice of hotspot or private Wi-Fi is likely to be as divisive and controversial as blocking particular Internet services,” Bubley writes.

In a blog entry, Bubley expands on this concept:

I’m increasingly convinced that mobile device / computing users will need sophisticated WiFi connection management tools in the near future. Specifically, ones that allow them to choose between multiple possible accesses in any given location, based on a variety of parameters. I’m also doubtful that anyone will want to allow a specific service provider’s software to take control and choose for them – at least not always.

We may see the emergence of “WiFi Neutrality” as an issue, if particular WiFi accesses start to be either blocked or “policy-managed” aggressively.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/The Future of Wi-Fi.flv[/flv]

Edgar Figueroa, chief executive officer of The Wi-Fi Alliance, speaks about the future of Wi-Fi. Wi-Fi technology has matured dramatically since its introduction more than a decade ago and today we find Wi-Fi in a wide variety of applications, devices and environments. (3 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe