Neville Chamberlain, British Prime Minister, 1937-1940

“If you don’t succeed, try, try, try again.” — Neville Chamberlain, 1938

Another day, another damage control effort from FCC chairman Thomas Wheeler, still reeling from days of criticism in response to his plan to revisit the issue of Net Neutrality next month.

In a lengthy blog post, Wheeler still believes it’s all a big misunderstanding:

“Some recent commentary has had a misinformed interpretation of the Open Internet Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) currently before the Commission,” writes Wheeler. “There are two things that are important to understand. First, this is not a final decision by the Commission but rather a formal request for input on a proposal as well as a set of related questions. Second, as the Notice makes clear, all options for protecting and promoting an Open Internet are on the table.”

Except they are not.

Wheeler channels former British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain by declaring a deep desire for “peace in our time” with half-measures instead of direct confrontation with Big Telecom interests.

“I believe this process will put us on track to have tough, enforceable Open Internet rules on the books in an expeditious manner, ending a decade of uncertainty and litigation,” Wheeler declares. “The idea of Net Neutrality (or the Open Internet) has been discussed for a decade with no lasting results. Today Internet Openness is being decided on an ad hoc basis by big companies. Further delay will only exacerbate this problem.”

The troubles with Net Neutrality are a problem of the agency’s own making and its leadership’s utter failure to show courage in the face of Verizon, Comcast, and AT&T’s power and influence. Former FCC chairman Michael Powell (now top cable industry lobbyist) created the problem when he invented a classification for broadband as an “information service” out of thin air without any clear authority. At the heart of Powell’s “policy statement” were four basic Internet principles:

- Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice.

- Consumers are entitled to run applications and use services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement.

- Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network.

- Consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.

Former FCC chairman Julius Genachowski who insisted the FCC had authority over broadband because he said so believed the best way forward was to involve the industry in the development of Net Neutrality policies they could live with. After multiple private phone conversations and closed-door meetings, companies like Verizon helped write the guidelines for protecting the Open Internet and then, after they were implemented, sued the FCC in federal court.

“We are deeply concerned by the FCC’s assertion of broad authority for sweeping new regulation of broadband networks and the Internet itself,” said Michael E. Glover, Verizon’s senior vice president and deputy general counsel. “We believe this assertion of authority goes well beyond any authority provided by Congress, and creates uncertainty for the communications industry, innovators, investors and consumers.”

That’s gratitude for you, and it wasn’t the first time.

Phillip “Your Wallet = Czechoslovakia” Dampier

In 2010, an exasperated D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals didn’t exactly encounter Perry Mason when the FCC legal team showed up to defend its order demanding Comcast cease throttling broadband traffic. When the FCC threatened to fine Comcast, the cable company sued claiming the FCC had no authority over how they run their broadband business. Commission lawyer Austin C. Schlick delivered a less-than-robust defense of the FCC’s scheme.

“If I’m going to lose I would like to lose more narrowly,” Schlick confided. “But above all, we want guidance from this Court so that when we do this rule-making, if we decide rules are appropriate we’d like to know what we need to do to establish jurisdiction.”

Justice A. Raymond Randolph had none of it.

“We don’t give guidance,” Randolph grumbled, “we decide cases.” The FCC lost.

Legal experts already knew the FCC was on thin ice. First, the Powell’s statement was never codified by the Commission’s own rulemaking procedure. Second, the Commission framed the broadband policy as a set of “guidelines,” a term considered legally vague. Third, the FCC relied on the concept of “ancillary” authority — borrowing regulatory authority from so-called “policy statements” coming from Congress, to claim jurisdiction.

DC Circuit Court

So it should come as no surprise that the same framework declared invalid when the FCC tried to spank Comcast was just as useless in shoring up the FCC’s authority to enforce Net Neutrality.

U.S. Circuit Judge David Tatel, writing for a three-judge panel, said that while the FCC has the power to regulate Verizon and other broadband companies, it chose the wrong legal framework for its open-Internet regulations.

“Given that the commission has chosen to classify broadband providers in a manner that exempts them from treatment as common carriers, the Communications Act expressly prohibits the commission from nonetheless regulating them as such,” Tatel wrote.

Judge Tatel could not have been more clear. In his second ruling, he noted the FCC’s ongoing resistance to reclassify broadband service under the well-grounded definition of a “telecommunications service” is at the heart of the problem.

But Wheeler, like his immediate predecessor Julias Genachowski, still stubbornly grips Powell’s flawed framework like a life-preserver off the Titanic:

The FCC promises Verizon they won’t have to sue again.

I am concerned that acting in a manner that ignores the Verizon court’s guidance, or opening an entirely new approach, invites delay that could tack on multiple more years before there are Open Internet rules in place. We are asking for comment on a proposed a course of action that could result in an enforceable rule rather than continuing the debate over our legal authority that has so far produced nothing of permanence for the Internet.

I do not believe we should leave the market unprotected for multiple more years while lawyers for the biggest corporate players tie the FCC’s protections up in court. Notwithstanding this, all regulatory options remain on the table. If the proposal before us now turns out to be insufficient or if we observe anyone taking advantage of the rule, I won’t hesitate to use Title II. However, unlike with Title II, we can use the court’s roadmap to implement Open Internet regulation now rather than endure additional years of litigation and delay.

Here is some news Wheeler can use: No matter what policies the FCC enacts or how, if they run contrary to the interests of Big Telecom companies, they will sue anyway. Net Neutrality appeasement by collaboration did not stop Verizon from promptly suing the FCC to overturn in court the rules the company helped write.

Wheeler needs to deal his reclassification card or get out of the game. It is increasingly clear it is the only legal basis under which the Court of Appeals will readily accept the FCC’s authority to oversee broadband.

Wheeler has his own set of Powell-like principles – the Four No-No’s of the Net:

Let me be clear, however, as to what I believe is not “commercially reasonable” on the Internet:

-

Something that harms consumers is not commercially reasonable. For instance, degrading service in order to create a new “fast lane” would be shut down.

-

Something that harms competition is not commercially reasonable. For instance, degrading overall service so as to force consumers and content companies to a higher priced tier would be shut down.

-

Providing exclusive, prioritized service to an affiliate is not commercially reasonable. For instance, a broadband provider that also owns a sports network should not be able to give a commercial advantage to that network over another competitive sports network wishing to reach viewers over the Internet.

-

Something that curbs the free exercise of speech and civic engagement is not commercially reasonable. For instance, if the creators of new Internet content or services had to seek permission from ISPs or pay special fees to be seen online such action should be shut down.

But there are plenty of loopholes in Wheeler’s proposals. First, “degrading service” goes undefined. As we’ve seen recently, there is a difference between purposely throttling a broadband connection and not maintaining and upgrading it to handle growing traffic. Second, Wheeler’s idea of what is “commercially reasonable” is not defined either. A provider could make all of its owned sports networks exempt from usage caps. That is neither “exclusive” or “prioritized.” It just doesn’t count against your usage allowance. Third, you might have open access to all of this content but won’t want it because your provider’s preferred partners get faster and more responsive service and less waiting for pages or videos to load.

Wheeler’s apparent naiveté about this industry and its behavior is beyond belief considering the decades he worked on behalf of the cable and wireless industry. Netflix foreshadows an Internet future without robust Net Neutrality. Verizon, Comcast and others ignore complaints about the degrading performance of Netflix, refusing to upgrade their connections of behalf of paying customers, until Netflix also agrees to pay them. When Netflix drops a check in the mail, the problem disappears. It doesn’t seem to matter that customers paying a very high price for Internet service cannot get the service they deserve unless someone else also pays.

If we can see this problem, it is extraordinarily curious why Wheeler cannot (or will not). Wheeler’s tough talk is cheap, but American broadband is not. Without direct action that reclassifies broadband as a telecommunications service, nothing Wheeler proposes or gets enacted is likely to survive the next inevitable court challenge.

Subscribe

Subscribe

One way to prove the merged company would not offer better service is to alert the Commission Comcast plans to reimpose usage caps on its customers while Time Warner Cable does not have any compulsory usage limits or usage billing.

One way to prove the merged company would not offer better service is to alert the Commission Comcast plans to reimpose usage caps on its customers while Time Warner Cable does not have any compulsory usage limits or usage billing. “Comcast Corp.’s bid to buy Time Warner Cable Inc. may be the opening act for a yearlong festival of telecommunications deals that would alter Internet, phone and TV service for tens of millions of Americans.” — Bloomberg News, May 14, 2014

“Comcast Corp.’s bid to buy Time Warner Cable Inc. may be the opening act for a yearlong festival of telecommunications deals that would alter Internet, phone and TV service for tens of millions of Americans.” — Bloomberg News, May 14, 2014

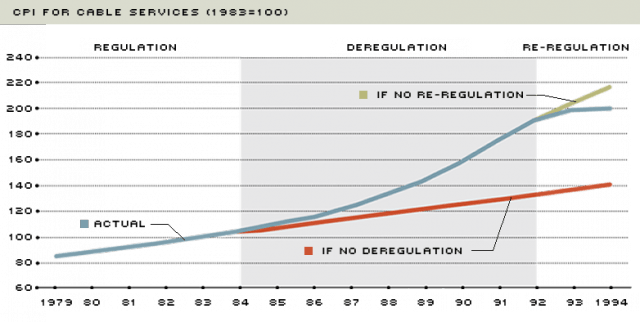

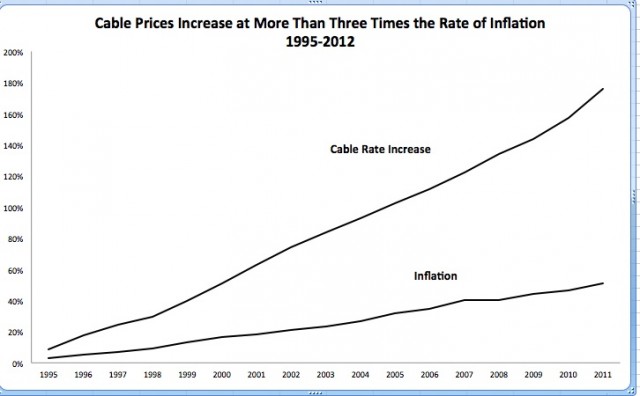

Economists reviewing data found in publicly available corporate balance sheets soon found evidence that the “increased programming costs”-excuse for rate increases did not hold water. The less competition or number of choices available to consumers in the market unambiguously lead to higher prices. It has remained true since Consumers’ Union

Economists reviewing data found in publicly available corporate balance sheets soon found evidence that the “increased programming costs”-excuse for rate increases did not hold water. The less competition or number of choices available to consumers in the market unambiguously lead to higher prices. It has remained true since Consumers’ Union  When a cable operator pays such an outrageous price, the previous owner is reaping the financial rewards of his monopoly power. The acquiring company can only pay such a high price by assuming that his monopoly power will allow him to continue to increase prices. Monopoly power is being bought and sold and borrowed against. The new cable operator, who has paid for market power, may insist that the debt he has incurred to obtain it is a real cost on his books. That may be correct in the literal sense (he owes someone that money) but that does not make it right, or the abuse of market power legal.

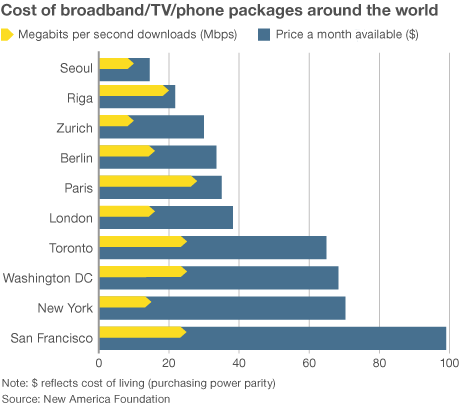

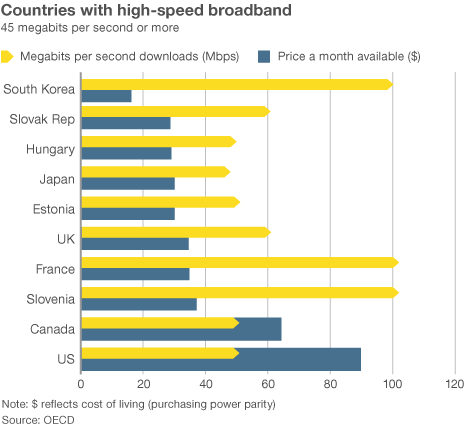

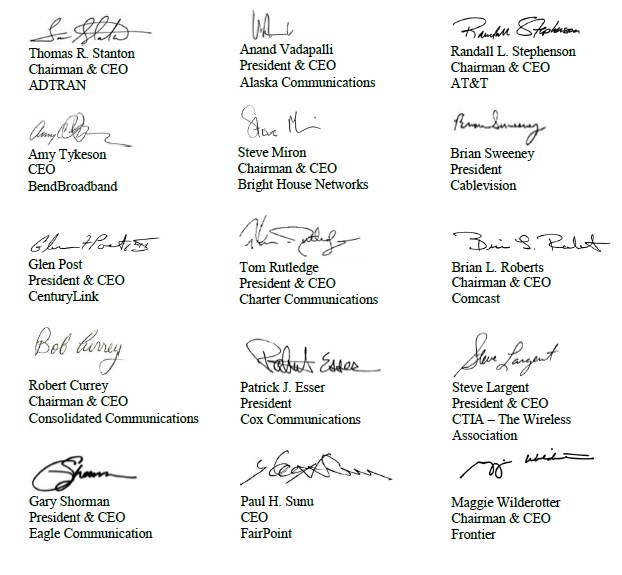

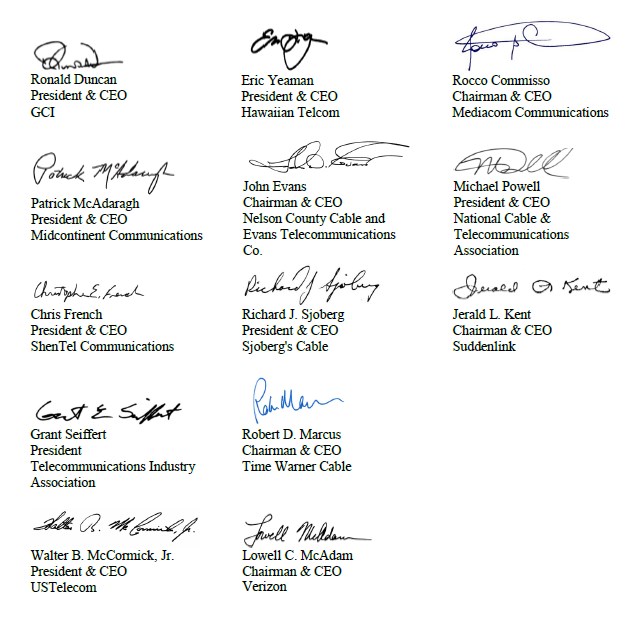

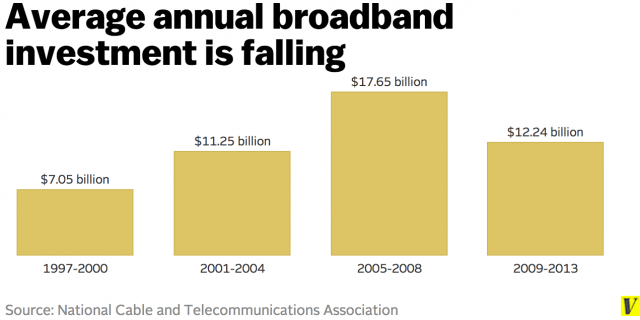

When a cable operator pays such an outrageous price, the previous owner is reaping the financial rewards of his monopoly power. The acquiring company can only pay such a high price by assuming that his monopoly power will allow him to continue to increase prices. Monopoly power is being bought and sold and borrowed against. The new cable operator, who has paid for market power, may insist that the debt he has incurred to obtain it is a real cost on his books. That may be correct in the literal sense (he owes someone that money) but that does not make it right, or the abuse of market power legal. Most of the same telecom companies that want to create Internet paid fast lanes, drag their feet on delivering 21st century broadband speeds, refuse t0 wire rural areas for broadband without government compensation, and have cut investment in broadband expansion are warning that any attempt by the FCC to enact strong Net Neutrality policies will “threaten new investment in broadband infrastructure and jeopardize the spread of broadband technology across America, holding back Internet speeds and ultimately deepening the digital divide.”

Most of the same telecom companies that want to create Internet paid fast lanes, drag their feet on delivering 21st century broadband speeds, refuse t0 wire rural areas for broadband without government compensation, and have cut investment in broadband expansion are warning that any attempt by the FCC to enact strong Net Neutrality policies will “threaten new investment in broadband infrastructure and jeopardize the spread of broadband technology across America, holding back Internet speeds and ultimately deepening the digital divide.”

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.

Powell’s principles stood as long as the FCC’s policies moved in lock-step with the telecommunications industry. When the FCC strayed from industry talking points and started showing some enforcement teeth, some of the same telecom companies that send the FCC cupcakes took them to court.