Tom Wheeler circa 1983, when he represented the cable industry. (Image: The Cable Center)

Skepticism persists over whether new FCC chairman Tom Wheeler, a former cable and telco lobbyist and venture capitalist, will have the interests of an industry he was a part of for decades ahead of the people he is supposed to represent.

The doubts are so significant, The Wall Street Journal’s ‘All Things D’ devoted an entire piece on the subject, interviewing Wheeler about his plans for the federal agency.

“My client today is the American people, and I am going to be the most effective advocate they could hope for,” Wheeler told AllThingsD in a phone interview on Wednesday. “I was (involved in) the early days of cable television when everybody was trying to squash it; I was a was champion for a diversity of voices and the competition that represented. I’m very proud of that period, but it was 30 years ago that I was in in cable, and 10 years ago that I was in wireless.”

Both periods were extremely important for both industries. When Wheeler was president of the National Cable TV Association (now the NCTA), his leadership helped enact the 1984 nationwide deregulation of the cable television industry. Wheeler promised the single national “hands-off” policy for cable television would put control “back in the hands of customers” instead of the local, state, and federal government. The cable lobby pushed hard for extra provisions in the law that would prohibit local or state governments or franchising authorities from reimposing controls the federal government eliminated.

The 1984 Cable Act contained three major provisions to strip away regulatory/rate oversight:

- “Basic Cable” rate regulation was removed in any community where a cable company faced “effective competition” from at least three unduplicated over the air television stations. If your community received two fuzzy network affiliates and one local religious station, that was considered effective competition.

- Local franchise authorities and cable TV commissions, often citizen-run, had most of their oversight and enforcement powers stripped away, including the most important power to deny a franchise renewal to a bad-acting local cable company, except in the most extreme cases. Cable operators effectively used this provision to launch costly lawsuits burying local communities in litigation expenses when they tried to find a different provider.

- Granted local franchise authorities to right to demand cable systems set aside a few channels for Public, Educational, and Government (PEG) use.

The cable industry carefully lobbied for an effective definition of “competition” that made it into the final version of the bill. Estimates from congressional researchers predicted that 97 percent of the country’s cable systems would be deregulated when the law took effect Dec. 29, 1986.

In a 1984 C-SPAN call-in program, Wheeler noted that before deregulation, “the cities were in the driver’s seat” controlling the franchising process. Wheeler claimed cable operators competing for franchise agreements were forced to promise services and technology that ultimately proved too burdensome or expensive to actually deliver. Deregulation, Wheeler promised, would “keep cable rates low because you are not going to be paying for services that [the government says] have to be provided that nobody watches.”

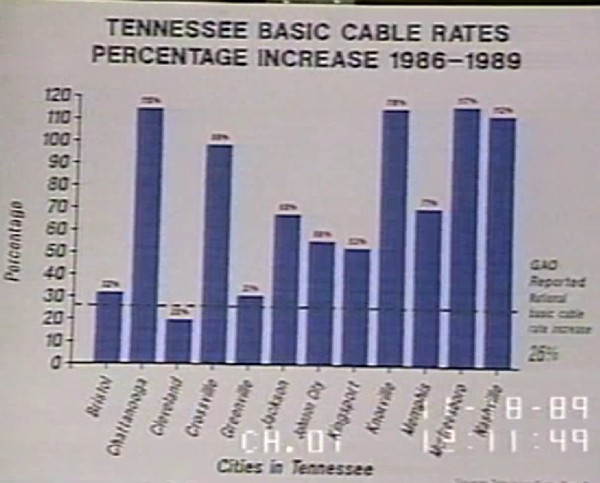

In reality, after the passage of the 1984 Cable Act, cable systems were bought and sold in a frenzy that left control ultimately in the hands of a handful of operators. Soon after, cable rates skyrocketed and cable-industry-owned networks and channels were shoveled on to cable lineups. With every sale and every new channel addition, rates were raised even higher, whether customers wanted the extra programming or not.

In reality, after the passage of the 1984 Cable Act, cable systems were bought and sold in a frenzy that left control ultimately in the hands of a handful of operators. Soon after, cable rates skyrocketed and cable-industry-owned networks and channels were shoveled on to cable lineups. With every sale and every new channel addition, rates were raised even higher, whether customers wanted the extra programming or not.

Without oversight, cable service itself deteriorated in quality. In some cities, cable operators ignored rights-of-way and often refused to hang or bury cable lines left scattered on lawns. Customer complaints often went unresolved for days or weeks. Cable operators also rolled out new charges for monthly programming magazines and equipment, even as they continued to boost rates for basic cable itself. Prior to deregulation, customers usually paid less than $10 a month for basic cable. After, rates rapidly pushed towards the $20 a month mark. Today’s cable TV prices are much higher.

In the summer of 1984, Wheeler left the NCTA to pursue a new business – The NABU Network, a precursor to cable broadband that turned out to be a commercial failure. The NABU Network coupled a home computer system with a cable-based data service. The only significant North American trial of NABU was in Ottawa, Canada and required significant subsidies from the Canadian government. Wheeler said the NABU system would offer subscribers a mountain of software at a monthly subscription price. Canadians had to buy the NABU PC for around $950 and pay around $10 a month for software access.

The venture fell apart because cable systems in that era lacked two-way capability, making it cumbersome for users to interact with the NABU platform or manage applications. Ottawa Cablevision and Skyline Cablevision introduced NABU in 1983 and discontinued it in 1985.

In 1992, Wheeler went on to become president of CTIA – The Wireless Association, the nation’s biggest cell phone industry trade group. Wheeler beefed up the association’s lobbying forces after joining, turning CTIA into “one of the most influential lobbying forces on Capitol Hill,” according to Connected Planet.

Once there, Wheeler presided over efforts to get government spectrum policies relaxed and keep cancer questions about RF energy leaking from cellphones under wraps:

In a 1994 memo, Wheeler raised objections to a draft of a mobile-phone manual that, among other things, advised consumers how to limit radio-frequency radiation from mobile phones. The book says Wheeler succeeded in getting the industry consumer safety document watered down.

In a September 1994 memo, Wheeler mapped out “a pre-emptive strike” on Rep. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) by highlighting to Markey the involvement of Harvard University. Wheeler, according to the book, even had a backup plan to curry favor with Markey that, if necessary, would “send all cash through Harvard.”

By 2000, Wheeler was being questioned about conflict of interest charges about his lucrative investments in businesses represented under the CTIA’s public policy umbrella, according to RTR Wireless:

But conflict-of-interest issues-real, perceived and otherwise-that flow from Wheeler’s lucrative ties to Aether, OmniSky and now, Metrocall, could have long-term consequences that CTIA and the wireless industry would rather not consider in these halcyon days of soaring stocks, consolidation and deregulation.

The unorthodox arrangement Wheeler has with outside wireless firms begs closer scrutiny by CTIA’s board. Do Wheeler’s money and management ties to firms he advocates set a bad precedent? Could it diminish CTIA’s credibility as an organization?

Wheeler claims to be committed to three principles that will govern how he looks at issues before the FCC:

- Is it good for competition? “You can’t have economic growth if you don’t have competition. You can put me down as rabidly pro-competition,” Wheeler said.

- Trust between those who run networks and those who use them must be maintained.

- Opening up high-speed networks must include guarantees that content will be open and accessible to all. “I am pro-the ability of individuals to access an open network,” he said.

Wheeler asked for a review of all proposals before the FCC and expects that in two months.

Tom Wheeler, then retiring president of the National Cable TV Association (NCTA), appeared on this fascinating 1984 C-SPAN call-in program at the NCTA Convention with future president Tom Mooney. The NCTA promised deregulation would deliver many benefits to cable subscribers. They got higher bills and declining service instead. (June 5, 1984 – 39:00)

Subscribe

Subscribe

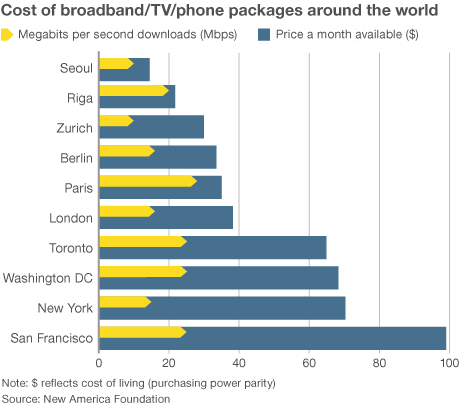

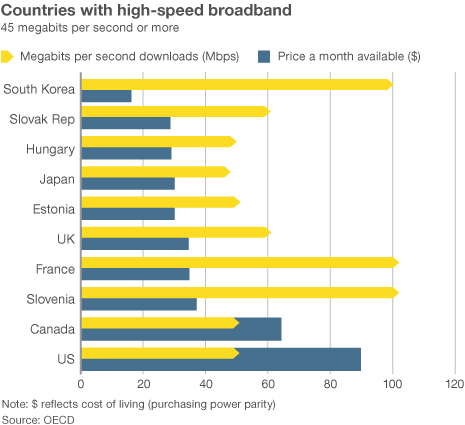

Broadband in the United States costs far more than in other countries —

Broadband in the United States costs far more than in other countries —  “Americans pay so much because they don’t have a choice,” said Susan Crawford, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama on science, technology and innovation policy. “We deregulated high-speed Internet access 10 years ago and since then we’ve seen enormous consolidation and monopolies, so left to their own devices, companies that supply Internet access will charge high prices, because they face neither competition nor oversight.”

“Americans pay so much because they don’t have a choice,” said Susan Crawford, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama on science, technology and innovation policy. “We deregulated high-speed Internet access 10 years ago and since then we’ve seen enormous consolidation and monopolies, so left to their own devices, companies that supply Internet access will charge high prices, because they face neither competition nor oversight.”

AT&T is hunting for buyers of its massive network of 10,000 cell towers worth about $5 billion to defray the costs of Wall Street-pleasing stock buybacks and fund potential acquisition deals in Europe.

AT&T is hunting for buyers of its massive network of 10,000 cell towers worth about $5 billion to defray the costs of Wall Street-pleasing stock buybacks and fund potential acquisition deals in Europe.

Wall Street investment banks will do better than American and British tax authorities, dividing at least $1.3 billion in financing, merger, and legal fees surrounding the Verizon deal. Many of New York’s largest investment banks are taking part in the transaction.

Wall Street investment banks will do better than American and British tax authorities, dividing at least $1.3 billion in financing, merger, and legal fees surrounding the Verizon deal. Many of New York’s largest investment banks are taking part in the transaction. Verizon hopes being the master of its own destiny will allow the company to innovate its wireless network towards future revenue opportunities, especially in the machine to machine connectivity business. Both AT&T and Verizon Wireless are racing to enable medical devices, home appliances, electric meters, and automobiles to communicate over their respective wireless networks. Both companies are concerned that the cell phone marketplace has become saturated in the United States, with most people desiring cell phone service already having it. With Wall Street demanding ongoing growth quarter after quarter, new revenue sources are more important than ever.

Verizon hopes being the master of its own destiny will allow the company to innovate its wireless network towards future revenue opportunities, especially in the machine to machine connectivity business. Both AT&T and Verizon Wireless are racing to enable medical devices, home appliances, electric meters, and automobiles to communicate over their respective wireless networks. Both companies are concerned that the cell phone marketplace has become saturated in the United States, with most people desiring cell phone service already having it. With Wall Street demanding ongoing growth quarter after quarter, new revenue sources are more important than ever.