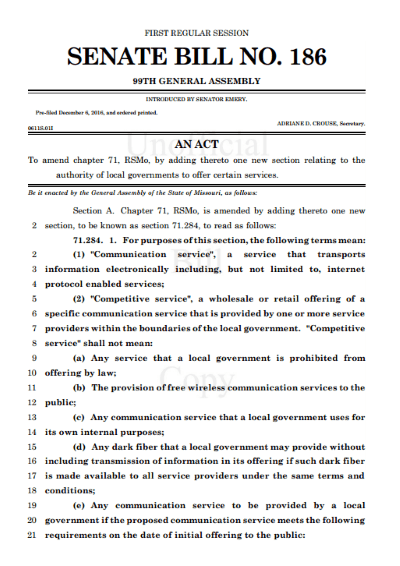

Emery

It’s 2017 and a lot of Missouri residents are still tortured by the lack of access to basic broadband service, and if a community broadband ban bill becomes state law it will remain that way for years to come.

SB 186 is essentially a copy of last year’s community broadband ban that eventually died in the legislature. Just like last year, many of the sponsors and promoters of the latest attempt to impose a municipal broadband ban have close ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and receive copious amounts of money from Missouri’s largest telecom companies. Some even win awards from the state’s biggest telecom lobbyists.

State Sen. Ed Emery (R-Lamar) loves the headlines he attracts from throwing ideological bombs into the public debate (he called homosexuality a mental illness, compared public education to slavery and a pathway to prison, and questioned whether former president Barack Obama was actually an American citizen). But he is not in touch with the rural residents in his state who have had their pleas for broadband service ignored by AT&T and other telecom companies for years.

Emery is a big fan of ALEC and serves as a Missouri state chairman. In 2015 he told an audience at an ALEC event he found the group’s efforts inspiring and helpful. ALEC acts as a giant clearinghouse for corporate-inspired legislation that ends up in the hands of friendly state legislators. ALEC’s model bills, including one banning municipal broadband, win passage in part because state legislatures do not get the kind of media attention and public scrutiny seen in Washington. SB 186, its predecessor, and other similar bills introduced in other states are frequently ghostwritten by telecom company lawyers and lobbyists and are designed to stop municipal broadband networks before they can get started.

Emery’s current bill is designed to apply a “scorched earth” response to communities trying to find ways to get rural broadband service up and running after a decade of being ignored by private telecom companies. It’s corporate protectionism and welfare at its finest, with a thicket of language that would force public providers into price and speed regulation. Emery’s bill would interfere with the types of loan agreements communities could contemplate to provide the service, and the language required for a mandatory referendum is heavily slanted to suggest such service is redundant and unnecessary. Emery’s bill also offers assurances his business friends could get gigabit speeds from community-owned providers, but not necessarily consumers.

Emery’s current bill is designed to apply a “scorched earth” response to communities trying to find ways to get rural broadband service up and running after a decade of being ignored by private telecom companies. It’s corporate protectionism and welfare at its finest, with a thicket of language that would force public providers into price and speed regulation. Emery’s bill would interfere with the types of loan agreements communities could contemplate to provide the service, and the language required for a mandatory referendum is heavily slanted to suggest such service is redundant and unnecessary. Emery’s bill also offers assurances his business friends could get gigabit speeds from community-owned providers, but not necessarily consumers.

Like the failed broadband hit bill introduced in Virginia, SB 186 is an ironic piece of legislation, heavy-handed with regulation and micromanagement and anchored with bureaucratic requirements designed to guarantee disappointment and costly failure. Emery’s career in public life has been spent railing against costly and unnecessary overregulation, yet his bill exemplifies both in action.

SB 186 also protects the status quo for broadband in Missouri, which is dreadful outside of major cities. It would assure incumbent telecom companies won’t face any service-improving competition and keep municipalities off their turf. For example, Columbia Water and Light has a “dark fiber” institutional fiber network at its disposal that is woefully underutilized. In addition to helping provide some connectivity for local government functions, the city-owned network also leases connections to hospitals and other public buildings, as well as some businesses. But the utility does not sell internet service itself.

The city believes much of the fiber network’s capacity is sitting un-utilized and could prove a valuable asset to the local connectivity economy. With the fiber already in place, expanding the network could be a cost-effective/common sense way to reach city residents that want better internet service than what incumbents are offering, and the city is more than willing to open the network up to those incumbents as well. SB 186 could eliminate that option in Missouri, just to protect the same private companies that have delivered underwhelming service for years.

In cities like Centralia, now exploring enhanced smart grid technology to improve the area’s electricity infrastructure, SB 186 would make the upgrade much more costly. Smart grid technology relies on fiber optic technology, often laid deep into neighborhoods and office parks. Only a tiny portion of that capacity is used to monitor utility infrastructure. The rest of the bandwidth on the fiber optic cable — already in place, could easily offer gigabit broadband service to every resident and business, especially if the city wires fiber to or near individual utility meters. That wouldn’t be allowed under SB 186 either, so communities like Centralia could not recoup some of the cost of the fiber optic technology by selling broadband service. That’s great news for companies like AT&T, CenturyLink, and Charter Communications. It’s also a relief for the phone companies who need not invest in their networks to offer something better than 20th century DSL.

Rural America: not a broadband-a-plenty

Emery offers two contradictory defenses for his bill:

- It is necessary to protect taxpayers from municipal broadband which Emery calls “unsuccessful, leaving ratepayers to cover debt costs.” But when asked by local media for any examples of a Missouri public broadband project that has failed, he could not.

- “We need more private-sector opportunities and not drive them out or hinder offerings coming into a community.”

In other words, Emery believes all public broadband networks are failures -and- they represent a major threat to private telecom companies that will be discouraged from investing in broadband expansion because a publicly owned competitor could be ready to “drive them out.”

Of course, neither is true. In rural Missouri there is no line of eager telecom companies seeking to expand broadband service into unprofitable rural communities and where only one broadband provider exists, there is no pressure to improve service quality or speed. In the first instance, there is no investment by private companies to discourage and in the second, the presence of a new provider encourages upgrades and investment. It’s a concept called “competition.” Sen. Emery would have a difficult time providing the name(s) of telecom companies that exited a community because of the presence of a municipal broadband alternative.

Rural farms are among the least likely places to get adequate internet service.

Sen. Emery’s family has a feed and grain business background, and those businesses (as well as Missouri’s farmers) are among the hardest hit economically by the lack of suitable broadband. But Emery is now far away from the business his father and grandfather ran. These days, he harvests big dollar contributions from some of the country’s largest corporations and much of his last campaign was financed by just two families — one with a vendetta against unions and the other — Rex Sinquefield — bucking to be Missouri’s own version of the Koch Brothers, who has his own private agenda he’d like enacted into law. Sinquefield has close ties to the Grow Missouri PAC, that also has close ties to the Club for Growth, ALEC, and the Koch Brothers’ backed Americans for Prosperity. Birds of a feather flock together.

Missouri’s biggest telecom companies are also generous contributors to Sen. Emery, which isn’t a surprise considering his bill and voting record directly benefits their businesses in the state. That may explain why the Missouri Cable Telecommunications Association — the state’s top cable lobbying group — gave Emery its Legislator of the Year award. Not to be outdone, the phone companies’ Missouri Telecommunications Industry Association gave Emery its own Leadership Award. Anyone who can introduce a bill that eliminates the best prospect of competition in suburban and rural Missouri for years is probably worthy of both.

In return for favors like that, some familiar names appear at the top of Emery’s list of campaign contributors:

In return for favors like that, some familiar names appear at the top of Emery’s list of campaign contributors:

- AT&T ($6,000)

- Comcast ($4,000)

- Verizon Communications ($4,000)

- CenturyLink ($3,500)

- Charter ($2,000)

- Time Warner Cable ($1,500)

- Charter Communications ($1,325)

- Sprint ($1,000)

Emery clearly listens to their interests more than average Missouri consumers still searching for broadband service.

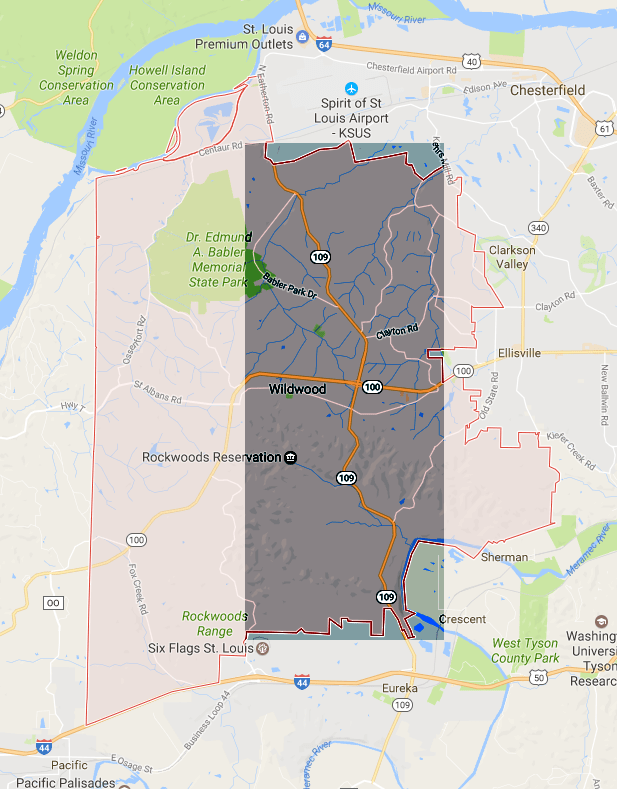

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported last summer that there are significant gaps in broadband coverage even in St. Louis County, where one million residents live. “Fringe suburban spots” too costly to meet Return On Investment requirements guarantee no service, indefinitely. In St. Clair County, 5,000 homes are without broadband for the same reason. In large parts of the state, what constitutes broadband no longer meets that definition — 25Mbps, as established by the FCC. Every telephone ratepayer pays a “universal service fee” on their phone bill, in part to extend broadband into rural areas. But that extension has been spotty because not every phone company accepts the money and the conditions that come with it to broaden their reach. That leaves many rural Missourians with <1Mbps DSL service. That’s the case in Wildwood, where streaming media is out of the question because internet speeds are too low.

The Broadband Berlin Wall: Wildwood, Mo. — Broadband service is easily available to the east of Highway 109. But to the west, service is spotty to non-existent.

Wildwood — in western St. Louis County, is living in “Third World conditions,” even though “we’re not in rural Timbuktu,” according to resident Marilyn Gilbert. It’s also comparable to Cold War-era Berlin, except in reverse. Eastern Wildwood offers residents broadband options from both Charter and AT&T. But the Broadband Berlin Wall dividing the community — Highway 109, separates the broadband haves’ from the have-nots’. The larger part of Wildwood to the west, now growing with new housing and businesses, is a broadband swamp with few, if any choices for local residents.

Gilbert “enjoys” AT&T DSL and speeds that never come close to 1Mbps. It is her only option.

“I tried to download my Windows update and it timed out,” she said. “The amount of time you waste waiting for things to open up or download!”

Remember, this is in St. Louis County, the old home for the headquarters of Charter Communications, which dominates the city of St. Louis.

Despite earning billions every year from the broadband business, Charter has refused to extend its lines of service into the western half of Wildwood, despite efforts to attract the company that date back six years. Residents report broadband availability is among their top concerns taken to local officials, who have in turn sought help from Charter, AT&T, and the state legislature.

The city of Wildwood’s efforts were met with a demand by Charter to pay the cable company $3 million in taxpayer funds to extend service. The city said no.

“The comment we hear constantly is that kids need high-speed (internet) in order to access their school work,” said Wildwood councilman Larry McGowen. “These days, internet is just like another utility. It has become every bit as important in people’s lives as electricity.”

But it apparently is not important enough to allow Wildwood and other communities the option of constructing their own local broadband solutions for residents if Emery’s bill becomes law.

Ironically, the same companies that refuse to extend their service into rural Missouri are also vehemently opposed to letting local governments do it in their absence.

The stalemate has caused some residents to sell their homes and move, just to get internet access. David Norell left town because he couldn’t survive with satellite internet service, which costs $80 a month and offers spotty service with a low data allowance.

That makes Emery’s bill, and others like it, a travesty. Banning local communities from doing the job large for-profit companies won’t seems nothing short of corporate protectionism. After all, as critics of Emery’s bill charge, how can a local government unfairly compete with a company that doesn’t compete at all? Also of concern is the fact those residents that do get token DSL service from AT&T may be trapped using it forever if Emery’s bill keeps better and faster service from co-ops and other public broadband options off the table.

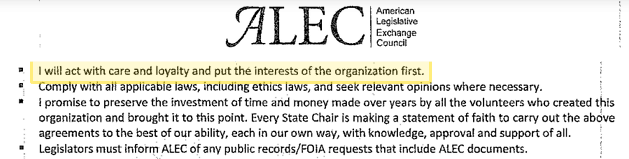

If it seems like Sen. Emery is putting the interests of big telecom companies – many dues-paying members of ALEC – above those of his constituents, perhaps he is. Consider the fact Emery is a state chairman at ALEC, an organization that included this loyalty pledge in its draft state chair agreement:

I will act with care and loyalty and put the interests of the organization (ALEC) first.

Emery has taken heat for his ongoing love affair with ALEC before, including an ethics complaint about a $3,000 meal at the Dallas Chop House where Emery ate. ALEC’s corporate members picked up the tab. That kind of unethical conflict of interest, along with the aforementioned loyalty pledge, infuriated the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

Mr. Emery and his ilk can believe what they want, but they should play no part in allowing corporations to hide their agendas, and their lobbying expenses, by pretending to be something they are not. The proof is in ALEC’s actions, which as Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank outlined, hid itself behind closed doors in a meeting last week in the nation’s capital, pushing reporters away while claiming they had nothing to hide.

No, ALEC exists solely to hide. To hide money. To hide agendas. To hide its hijacking of democracy.

Lawmakers who care about the constitution and their commitment to voters should be fleeing faster than the corporations who realize ALEC is simply a bad investment.

Emery at a 2015 ALEC event.

It was not an isolated incident. Ed and his wife Rebecca Emery also enjoyed a $141.10 meal paid for by the Missouri Telecommunications Association. It’s safe to assume nobody had just a small salad. Other meals and drinks were courtesy of AT&T and CenturyLink. (Peabody Energy footed the bill for the Emerys’ taxi rides back and forth.)

When the wining and dining ended, the lobbyists were back with campaign contribution checks in hand.

These kinds of municipal broadband bans are toxic to economic development for rural communities that already face built-in economic and infrastructure disadvantages. The 21st century digital knowledge economy has the potential to make rural America equally competitive, assuming there is adequate infrastructure in place to participate.

Relying on private investment alone can work in urban areas where broadband profits are easy because the essential infrastructure to provide the service was constructed and paid for decades ago, originally to deliver telephone and television service. Rural areas suffer from deteriorated wireline infrastructure some phone companies want to abandon altogether and no cable broadband service at all.

Charter and AT&T first answer to shareholders. Local governments answer to their residents. Legislators are supposed to do the same. For Mr. Emery, loyalty to the interests of ALEC and the state’s telecommunications companies seems clear. It’s too bad his bill suggests a lot less loyalty to the voters in his district that need internet access or better broadband are will assuredly not get it if this bill ever becomes state law.

Subscribe

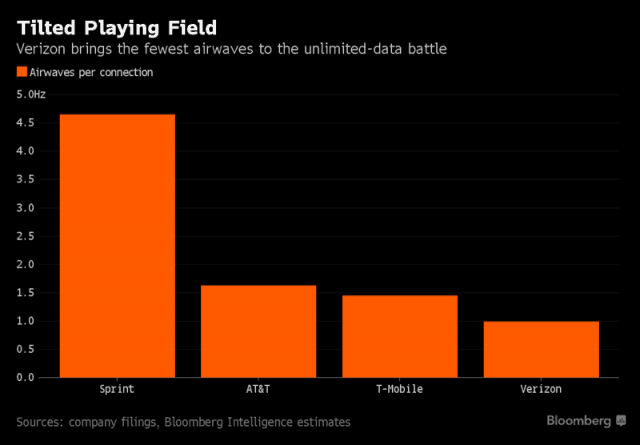

Subscribe Verizon Wireless’ new unlimited data plan threatens to destroy everything, fear Wall Street analysts in an open panic attack over the prospects of value destruction and network reliability damage.

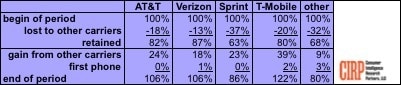

Verizon Wireless’ new unlimited data plan threatens to destroy everything, fear Wall Street analysts in an open panic attack over the prospects of value destruction and network reliability damage. What also concerns Wall Street is the increasing evidence an all-out price war provoked by T-Mobile and Sprint will threaten to close some doors on network monetization. Charging customers for data consumption has a growth prospect that would have guaranteed increasing average revenue per customer indefinitely. But unlimited plans mean consumers pay one flat price for data no matter how much they consume. Consumers love it. Wall Street analysts generally don’t.

What also concerns Wall Street is the increasing evidence an all-out price war provoked by T-Mobile and Sprint will threaten to close some doors on network monetization. Charging customers for data consumption has a growth prospect that would have guaranteed increasing average revenue per customer indefinitely. But unlimited plans mean consumers pay one flat price for data no matter how much they consume. Consumers love it. Wall Street analysts generally don’t.

Ten years earlier, Sprint was worth $69 billion and was prepared to dominate the U.S. wireless industry, but drove customers off with very poor customer service and inadequate investment in its network, allowing competitors like AT&T and Verizon Wireless to leap ahead. Sprint also embarked on an executive-inspired fantasy: a disastrous merger with Nextel that preoccupied the company for years. Softbank taking the lead has done little to change customer perceptions, nor those of some Wall Street analysts who fear Sprint is a bottomless money pit that always promises better times and profits are coming, but never seems to get there.

Ten years earlier, Sprint was worth $69 billion and was prepared to dominate the U.S. wireless industry, but drove customers off with very poor customer service and inadequate investment in its network, allowing competitors like AT&T and Verizon Wireless to leap ahead. Sprint also embarked on an executive-inspired fantasy: a disastrous merger with Nextel that preoccupied the company for years. Softbank taking the lead has done little to change customer perceptions, nor those of some Wall Street analysts who fear Sprint is a bottomless money pit that always promises better times and profits are coming, but never seems to get there.

Son’s argument to the new administration depends on President Trump and FCC Chairman Ajit Pai being more friendly to the idea of less competition than the Obama Administration. Son may have an uphill battle, considering the former Obama Administration’s opposition to earlier mergers, including T-Mobile and AT&T and T-Mobile and Sprint seems to have paid off for consumers in the form of today’s fiercer competition and a price war.

Son’s argument to the new administration depends on President Trump and FCC Chairman Ajit Pai being more friendly to the idea of less competition than the Obama Administration. Son may have an uphill battle, considering the former Obama Administration’s opposition to earlier mergers, including T-Mobile and AT&T and T-Mobile and Sprint seems to have paid off for consumers in the form of today’s fiercer competition and a price war.

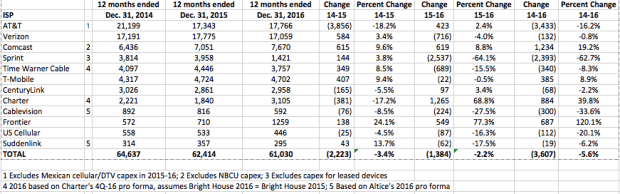

The FCC order approving the merger deal was hardly onerous, requiring Charter to compete head-to-head for customers in places the company can choose itself. Lawmakers eliminated exclusive cable franchise agreements years ago, but established major cable operators like Charter have gone out of their way to avoid competing in areas that already receive cable service. While Wheeler may have hoped some of that competition would be directed against fellow cable companies, Charter CEO Thomas Rutledge quickly made clear to investors and the FCC Charter would continue to avoid direct cable competition, instead promising to expand service into non-cable areas that already get DSL service from the phone company or no broadband at all.

The FCC order approving the merger deal was hardly onerous, requiring Charter to compete head-to-head for customers in places the company can choose itself. Lawmakers eliminated exclusive cable franchise agreements years ago, but established major cable operators like Charter have gone out of their way to avoid competing in areas that already receive cable service. While Wheeler may have hoped some of that competition would be directed against fellow cable companies, Charter CEO Thomas Rutledge quickly made clear to investors and the FCC Charter would continue to avoid direct cable competition, instead promising to expand service into non-cable areas that already get DSL service from the phone company or no broadband at all. Rutledge’s clear views about Charter’s expansion plans apparently never made it to the American Cable Association, a cable industry lobbying group that defends the interests of independent and smaller cable operators. Despite Rutledge’s public statements, the ACA and its members are afraid Charter could expand on their turf anyway, potentially forcing small cable operators to compete with the same level of service Charter offers. The horror.

Rutledge’s clear views about Charter’s expansion plans apparently never made it to the American Cable Association, a cable industry lobbying group that defends the interests of independent and smaller cable operators. Despite Rutledge’s public statements, the ACA and its members are afraid Charter could expand on their turf anyway, potentially forcing small cable operators to compete with the same level of service Charter offers. The horror. The real goal here is to minimize direct competition at all costs. The FCC’s deal conditions already included the need for more rural broadband expansion. Wheeler’s second goal was to introduce a new model — cable company competing against cable company — fighting for new customers by offering consumers better service and pricing. The existence of such competition would belie the industry’s claim that cable overbuilds and head-to-head competition is uneconomical. Wildly profitable, perhaps not, but certainly possible. Historically, the traditional way cable operators dealt with the few instances of direct cable competition was to buy them out to put them out of business. Rutledge was certainly thinking along those lines when he complained that the FCC’s order to compete did not include permission to eventually devour its competitor, effectively making competition go away.

The real goal here is to minimize direct competition at all costs. The FCC’s deal conditions already included the need for more rural broadband expansion. Wheeler’s second goal was to introduce a new model — cable company competing against cable company — fighting for new customers by offering consumers better service and pricing. The existence of such competition would belie the industry’s claim that cable overbuilds and head-to-head competition is uneconomical. Wildly profitable, perhaps not, but certainly possible. Historically, the traditional way cable operators dealt with the few instances of direct cable competition was to buy them out to put them out of business. Rutledge was certainly thinking along those lines when he complained that the FCC’s order to compete did not include permission to eventually devour its competitor, effectively making competition go away.

Verizon will invite several thousand customers in 11 cities to participate in a “pre-commercial”

Verizon will invite several thousand customers in 11 cities to participate in a “pre-commercial”