The Progressive Movement of the 1900s-1920s

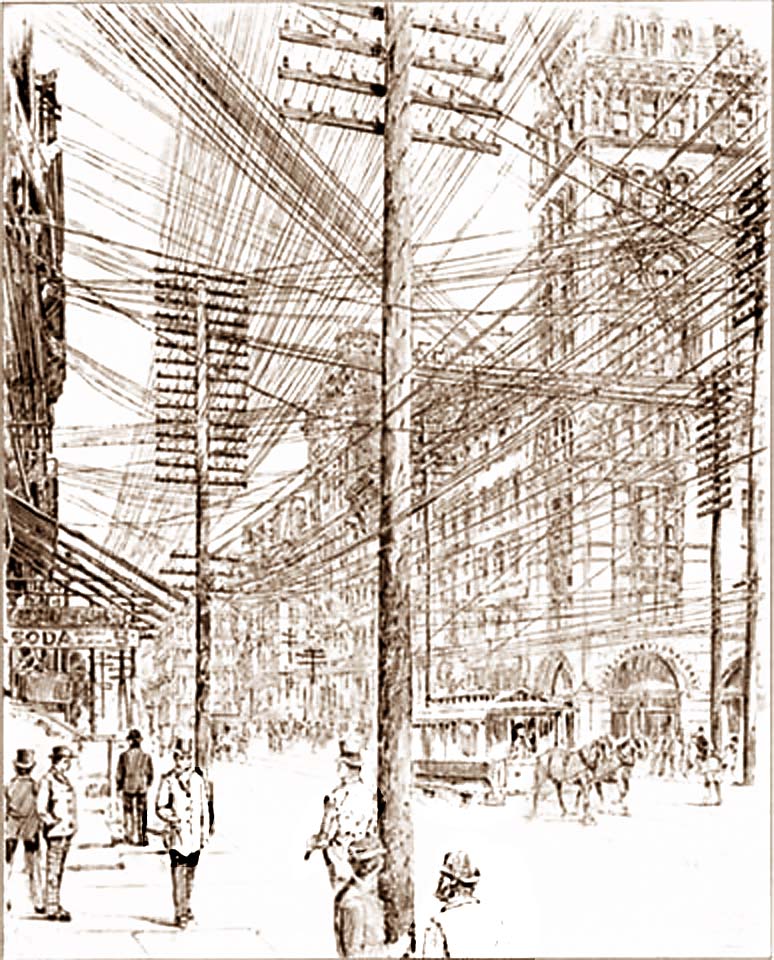

After the reform-driven progressive movement of the early 20th century was finished taking on the railroads, they turned their attention to so-called “utility services.” These were telephone, energy, and water providers.

The progressive movement of the early 1900s split into at least two camps:

- Individualist Progressives — Most people in this camp belonged to Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party. The Progressive party was made up mostly of disaffected centrists who left the Republican Party after Roosevelt failed to secure the 1912 Republican nomination for president. A rift had developed between Roosevelt and then-president Taft over how much energy should be devoted to breaking up corrupt big business and corrupt politicians. The Progressive Party believed the Republicans had developed an unholy alliance with big business, monopoly trusts, and corrupt politicians on the state and federal level. These individualist progressives believed in a well-regulated capitalist system, and with respect to energy companies, they demanded honoring the services and pricing promised consumers. Once those conditions were met, government should stay out of it. These progressives opposed abusive trusts and monopolies and supported competition. The Progressive Party had support in states like New York, Illinois, California, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — all states with a heavy manufacturing business base that suffered from monopoly abuses.

- Reformist Progressives — Reformist progressives believed essential services should be in the hands of public trusts or municipalities, operated as non-profit “utilities” answering to the communities they served. They were major advocates for municipal utility projects, and believed it was immoral for important services to be left in the hands of for-profit businesses, much less trusts and monopolies. Many reformist progressives rallied behind the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who loudly advocated radical reform in his newspapers. Hearst even formed the Municipal Ownership League, a local party in New York City, whose primary goal was to force for-profit utilities out of the marketplace — turning services over to municipalities to run for “the public good.” Reformist progressives often applied moral values to private enterprise, suggesting an improved capitalist model required companies to also consider the social good of operating in the public interest.

Where individualist progressives had control, rate regulation and oversight was the usual model when dealing with electric companies. California and Wisconsin, fed up with the railroad abuses, saw many similarities in electric monopolies. In the end, they applied the same rate regulation philosophy used with the railways for all utility services. Both states regulated rates charged based on their perception of fair pricing. Beyond that, they tended to leave private providers alone. New York’s governor Charles Evans Hughes was an individualist progressive who advocated regulatory crackdowns on monopolies who abused the terms and conditions under which they offered service. Once they met that obligation, Hughes believed the free market would manage to sort out the rest.

That was all fine and well for communities already served by electric companies, but what about vast numbers of smaller communities bypassed for electric service?

Defenders of the free market, and the companies themselves argued that only through deregulation would providers get sufficient investment to expand their service areas into previously unserved communities. Apply rate regulation and other government interference and investors will look elsewhere.

Reformist progressives disputed this assertion, believing hunger for quick profit was responsible for the disinterest in serving rural communities, where construction costs were higher and rapid return on investment was unlikely. Besides, they argued, since most of these companies provided monopoly service, it wasn’t as if they faced imminent price-cutting competition.

Reformers advocated bypassed communities should form their own municipally-run electric companies or cooperatives, managed by local government and answerable to local ratepayers. This solution was attractive to many communities, especially the growing number of planned new communities that came during the boom years of the 1920s.

As municipal power attracted attention, some in the private power sector balked. Not only were these companies delivering good service to customers, they were often doing it at far lower prices. Many large utility companies and their allies made municipal power a political issue, attacking the concept as anti-American. Their argument: Public money should never be spent to construct services traditionally provided by private companies, even when those companies had yet to wire those communities for service.

As political lobbying for bans on municipal power projects grew more intense, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst declared all-out war on the electric monopolies. Hearst advocated that electricity be a delivered only through not-for-profit municipally-run utility companies.

Hearst even went as far to seek the governor of New York’s office several times in the early 1900s, to implement his progressive reforms. Hearst’s platform included advocacy of public power delivered for the social good. That meant companies would extend service to outlying areas as soon as practical instead of when it was grossly profitable. Power companies would charge a fair price for good service. Companies would also advocate for customer safety and work with government to define safety regulations instead of reflexively opposing them at every turn.

In one of several runs for office, his opponent was the aforementioned then-current governor Charles Evans Hughes, who promptly went on the attack.

Hughes had one word for Hearst’s reform views: Socialism

Governor Hughes told the Republican Club of New York in 1908, “Our government is based upon the principles of individualism and not upon those of socialism…. It was founded to attain the aims of liberty, of liberty under law, but wherein each individual for the development and the exercise of his individual powers might have the freest [sic ] opportunity consistent with the equal rights of others.”

Hearst lost the governor’s race each time he ran, and was outmaneuvered by the private industries he sought to reform. In fact, the industry managed to outwit regulatory advocates at every turn.

For example, since states were permitted only to regulate commerce within its borders, giant national electricity holding companies, also known as “trusts,” typically escaped such regulation by opening headquarters out of state, which allowed them to ignore local and state regulations. In Riverside, California, Southern Sierras Power Company was able to ignore California state regulations because its head offices were in Denver, Colorado. That kept pesky state officials out of Sierras’ books to verify whether the rates it charged were fair.

When regulators sought to construct a formula for fair regulated pricing, creative bookkeeping and debt structuring made even confiscatory rates permissible. Companies learned to use business regulations against the regulators. For instance, when a regulator believed rates could be lowered, power companies increased their debt obligations, at least on paper. They paid outrageous administrative fees to the holding companies they themselves often quietly controlled. Or they used creative accounting tricks to make it appear free cash was obligated to satisfy investors who held company debt and had to be repaid under government rules within a limited time frame. Companies were able to “prove” to regulators their current rates were fair, and there was no leeway to reduce them.

Only after municipal power companies began providing service at dramatically lower, and sustainable prices did suspicion reach a fever pitch that regulators were being played.

Tomorrow: A “New Deal” for Americans

Subscribe

Subscribe