Who knew America’s largest cable and phone companies were in the broadband shortage business?

Broadband evangelist Craig Settles has been as outraged about this year’s crop of anti-broadband legislation as we have here at Stop the Cap!

He wrote about the implications of allowing state laws to be changed in favor of the big cable and phone companies in a piece published by GigaOM that details where these anti-community Internet bills are coming from:

This push is brought to you by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a group of corporate lobbyists who ghostwrite state bills behind closed doors that their pocket legislators then push on the floor. This “model” of anti-muni broadband legislation contains wording that is replicated in these latest bills and newspaper op-eds that attack community broadband.

Many of the nation’s largest phone and cable companies funnel funds into ALEC, and even sponsor wine-and-dine trips for state legislators and their families as part of a comprehensive effort to get their foot (and later proposed legislation) in the door.

Download this archive of ALEC-written and sponsored state legislation/policies affecting telecommunications and IT. (16mb .zip file)

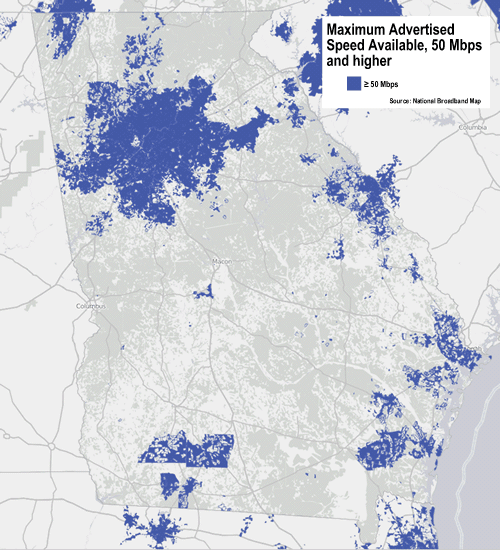

Few state legislators fully realize the implications of some of these measures, which can hamstring their state’s broadband networks into “good enough for you” broadband, as determined by Comcast, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, and others.

![]() ALEC’s dog-and-pony show opens with its corporate backers enhancing their campaign contributions to legislators likely to support their agenda. ALEC’s lobbyists can then provide “boilerplate” templates for legislation that can be slightly modified and introduced at the state level for consideration.

ALEC’s dog-and-pony show opens with its corporate backers enhancing their campaign contributions to legislators likely to support their agenda. ALEC’s lobbyists can then provide “boilerplate” templates for legislation that can be slightly modified and introduced at the state level for consideration.

With a significant increase in campaign contributions targeting friendly legislators, community broadband suddenly becomes a hot topic at the statehouse.

Legislators do not work alone to pass these measures. As we’ve seen in other states, industry-backed lobbying firms deliver a comprehensive set of support services for the campaign to stop community broadband competition:

- Talking points for legislators and others opposed to municipal Internet;

- Professionally produced mailers that can be distributed to every home in a community bashing community networks;

- Sample letters to the editor intended for local newspapers and easy-to-send letters to legislators asking them to support anti-broadband legislation;

- Help from seemingly “independent” outside groups that criticize such networks, without disclosing their funding comes, in part or whole, from the cable or phone company.

Being hoodwinked by the companies that want these kinds of bills passed leave your community’s broadband needs entirely in the hands of providers that have performed so poorly in some cities, local governments have decided they have to provide the service themselves. Settles illustrates the obvious:

This isn’t about unfair competition by local government. When Wilson’s 12-person IT department can plan, build and manage a network that can deliver speeds (up to a gig) 20 times faster than the best Time Warner Cable offers, that’s competing with superior technology. When Comcast customers switch to Chattanooga’s gig network because of their public utility’s better customer service, that’s competent competition. When tiny Reedsburg, Wis. refuses to compete against the large cable company on price, but beats competitors by offering greater value such as a better selection of Internet services, they compete based on local credibility.

So U.S. communities have to ask themselves, are they going to stay stuck on the train or will they be zipping along at warp speed?

Providers and their industry friends will always argue that you don’t need gigabit broadband speed — what you get from your cable or phone company today is “fast enough.” Some go as far as to argue current providers are equipped to deliver whatever service customers need, but the demand “just is not there.”

But as we argued on GigaOM ourselves, the nation’s largest telecom companies have already proven they apparently cannot meet the demand that exists today. That is because an increasing number of them have started to slap arbitrary usage caps and other limits on their customers’ broadband usage. Customers don’t want these Internet Overcharging schemes, yet they persist because of what providers effectively admit is a broadband shortage on their networks.

So for a city like Chattanooga, Tenn., which of the following providers should be punished (and potentially even banned) for being in the broadband business:

- AT&T, which delivers around 6-7Mbps DSL in suburban Chattanooga or up to 24Mbps on its U-verse platform with 150GB/250GB usage limits respectively;

- Comcast, which delivers up to 50Mbps over cable broadband with a 250GB usage cap;

- EPB Fiber, which delivers up to 1,000Mbps over fiber optics with no usage cap.

If you are AT&T or Comcast, clearly the provider that must be stopped is #3 — EPB Fiber. After all, you can’t be in the broadband shortage business when the competitor next door offers a broadband free-for-all made possible from an investment in a superior network that exists to serve customers, not shareholders and investment banks.

Subscribe

Subscribe