Drahi

After failing in a surprise bid to acquire Time Warner Cable out from under Charter Communications, European cable magnate Patrick Drahi has spent much of this summer quietly working to make sure that never happens again.

The French press is buzzing over Drahi’s decision to move his corporate headquarters from the business friendly Grand Duchy of Luxembourg — nestled between Belgium, France, and Germany — north to the Netherlands. The move is mostly on paper — attorneys drafted the agreement that effectively transferred Altice SA to Drahi’s Dutch subsidiary Altice NV and shareholders approved.

Why move the company from one of Europe’s most business-friendly countries to Holland, a country with a long history of corporate oversight? It wasn’t for the stroopwafels.

The Netherlands is rare among most European countries because it allows corporations to set up “dual-class share structures.” That means nothing to 99% of Dutch citizens and the majority of our readers, but it means a lot if you are a billionaire running a hungry multi-national corporation using other people’s money to gain control of companies on your acquisition list.

With the move, Drahi can embark on a breathtaking acquisition spree without diluting the control he has over his growing cable empire. Going forward, Altice will apply different voting rights to various classes of stock offered to investors. Drahi now holds 58.5% of Altice stock. But his shares are special because they grant him 92% of the voting power. Other shareholders will find they are not entitled to an equal say in how the public company is run.

With the move, Drahi can embark on a breathtaking acquisition spree without diluting the control he has over his growing cable empire. Going forward, Altice will apply different voting rights to various classes of stock offered to investors. Drahi now holds 58.5% of Altice stock. But his shares are special because they grant him 92% of the voting power. Other shareholders will find they are not entitled to an equal say in how the public company is run.

Altice admitted to regulators they designed the new share structure to give Mr. Drahi greater flexibility for financing and corporate transactions without threatening his control of the company. Altice called that “a value-enhancing strategy without diluting voting control.” This means Drahi can offer generous amounts of Altice stock to help fund future takeover deals without worrying that will reduce his control over the company.

If Drahi were to recklessly launch a spending spree of epic proportions to the consternation of shareholders, there will be little recourse and almost no chance of a shareholder revolt. But just to make sure, Drahi gets to pick six of Altice’s eight board members. He also won an agreement with board members who also hold shares in Altice granting him absolute and automatic support of all his proposals for 30 years. On top of that, he is entitled to “negative control” over the board, which means in any vote, he is allowed to cast a number of votes equal to all other board members.

With generous grants of authority like these passing muster, it’s no wonder executives of corporations around the world are urging consideration to move the corporate headquarters to the land of tulips and windmills. Fiat Chrysler already did, at the behest of Italy’s Agnelli family, which controls the Italian-American car company with a tight grip. Mylan, a producer of generic pharmaceutical drugs, managed to fend off Israeli rival Teva Pharmaceuticals, using Holland’s tolerance of executive-friendly poison pill maneuvers to keep unfriendly takeover artists away.

With generous grants of authority like these passing muster, it’s no wonder executives of corporations around the world are urging consideration to move the corporate headquarters to the land of tulips and windmills. Fiat Chrysler already did, at the behest of Italy’s Agnelli family, which controls the Italian-American car company with a tight grip. Mylan, a producer of generic pharmaceutical drugs, managed to fend off Israeli rival Teva Pharmaceuticals, using Holland’s tolerance of executive-friendly poison pill maneuvers to keep unfriendly takeover artists away.

Now that the move to an Amsterdam post office box is complete, Drahi is in the process of rearming his war chest for another assault on the American mainland. The French newspaper l’Humanité warns it is more conniving from the “telecom vampire” that sucked the blood out of competitive cable in France. The newspaper cited deregulation and privatization to be great for billionaires like Drahi, but a bad deal for consumers.

Since the 1990s, telecom executives in Europe and North America have promised regulators a lot in return for deregulation and self-oversight. Allowing companies a free rein would stimulate competition and private investment to finance and construct next generation networks, they claimed.

But l’Humanité uncovered another motivation for telecom magnates like Drahi: to get filthy rich. The newspaper quotes one well-known anecdote about why Drahi got into the cable business — because after studying Forbes articles ranking the fortunes of the 1%, Drahi set his sights on the industry where there were the most billionaires – telecommunications.

Keeping that newly privatized and deregulated wealth requires ruthlessness for others but protection for your allies and yourself. Drahi followed the teachings of American cable magnate John Malone (who is Charter Communications’ biggest shareholder today) and began a debt-fueled buying spree of independent cable systems, quickly followed by ruthless cost-cutting at the acquired companies, earning him the nickname “The Slasher,” among others less charitable. His critics say he has a lot of nerve, because in many instances Drahi billed the companies he acquired for consulting and management fees. BFM Business reports Drahi has only one bottom line when making up his mind: how much generated cash will come from the decision.

Keeping that newly privatized and deregulated wealth requires ruthlessness for others but protection for your allies and yourself. Drahi followed the teachings of American cable magnate John Malone (who is Charter Communications’ biggest shareholder today) and began a debt-fueled buying spree of independent cable systems, quickly followed by ruthless cost-cutting at the acquired companies, earning him the nickname “The Slasher,” among others less charitable. His critics say he has a lot of nerve, because in many instances Drahi billed the companies he acquired for consulting and management fees. BFM Business reports Drahi has only one bottom line when making up his mind: how much generated cash will come from the decision.

The real money would start rolling in at the height of the dot.com boom. Regulators accepted a bid by Drahi and two of his allies to create the fourth French telecom operator — a wireless venture known as Fortel. The three men promised to invest more than $3 billion building the network, an amount called “not credible” by some regulators and a number of industry leaders. But since the frequencies went to those who promised the most investment, Fortel won. Drahi was named president of the company.

Just before the dot.com bubble burst and Fortel seemed to be wavering, Drahi sold many of his interests to UPC, a European cable conglomerate owned by his mentor John Malone. In early 2001, the wireless project was scrapped and Fortel itself was sold for scrap, never to build the promised network. But by then, Drahi was working at UPC with Malone on a massive cable industry acquisition and consolidation strategy. During his career at UPC, Drahi was in charge of spending hundreds of millions of dollars to acquire French cable operators including: RCF, Time Warner Cable France, Rhone Cable Vision, and Videopole InterComm.

UPC declared bankruptcy in 2002.

Malone’s company quickly became overextended and very deep in debt when they suddenly stopped paying creditors in the fall of 2002. But before that happened, Drahi once again had the good fortune to cash out of UPC before the roof collapsed, selling his own Médiaréseaux cable system to Malone’s company at full value just before UPC went bankrupt. The bankruptcy that followed didn’t hurt Malone much and Drahi not at all.

Unwilling to rescue UPC’s faltering operations before bankruptcy, Malone waited until after the cable company went Chapter 11, when 65% of its debt was erased in court proceedings in return for a $99.8 million fresh infusion of cash from UGC/Liberty Media — another Malone-controlled venture that suddenly emerged with a checkbook. That bought Malone’s Liberty Media a 65.5% stake in the rescued company. Vendors, smaller debtors, and other shareholders fared far worse. Most received little, if any of the money owed them, and the remaining shareholders were given just 2% ownership of the company after it emerged from bankruptcy.

Drahi re-emerged on the French business scene after squirreling away his UPC cable proceeds in his new venture Altice, originally launched in Luxembourg, listed on the Amsterdam stock exchange, and controlled by another holding company owned by Drahi housed in the British tax haven of the Channel Islands. Drahi himself was, for a time, a Swiss resident domiciled in Canton Zermatt, another tax haven with tax thresholds that favor the super-wealthy. Drahi now qualifies.

Within four years of Altice’s existence, the company has acquired 99% of France’s cable systems. Drahi has since looked abroad to consummate more deals.

When an Israeli cable system became available to buy, Drahi suddenly became a citizen of Israel and rented an apartment in the country, mostly to meet Israel’s citizenship requirements to acquire the HOT cable system. After the sale was complete, HOT raised its rates, most recently by 20 percent.

Le Echos, a French newspaper, has watched Drahi plow his way through French telecommunications for several years and summed up Drahi’s acquisition strategy in three words: It’s never enough.

The newspaper suspects Drahi will continue using the same techniques he has used in France for the last 20 years to create an empire in the United States. He will take on massive amounts of debt and use Wall Street and French investment banks to pay for most of his acquisitions, combined with generous shares in Altice stock for shareholders and top corporate executives. With Altice’s relocation complete, Drahi can make generous offers his targets cannot refuse, even when they are privately owned.

To start an American cable empire, Drahi will have to acquire smaller cable operators to build leverage for potential takeovers of larger operators later. His ability to throw massive sums of money on the table makes it very likely his next targets will be Cox Communications and Cablevision — both controlled by families that have held on in the cable business despite years of tentative acquisition offers or sales explorations. Both Cox and Cablevision offer access to larger U.S. cities. Other likely targets, including Mediacom, Cable One, and Midcontinent Communications, don’t. He can digest those companies later.

On June 24, Drahi told his fellow dinner guests at the Polytechnique Foundation, “For me, telecom is like pinball,” Drahi said. “As long as there are balls, I will play.”

Subscribe

Subscribe

That philosophy may still cost cable companies customers if a fiber competitor doesn’t have to compromise speed and performance and can afford to charge less.

That philosophy may still cost cable companies customers if a fiber competitor doesn’t have to compromise speed and performance and can afford to charge less.

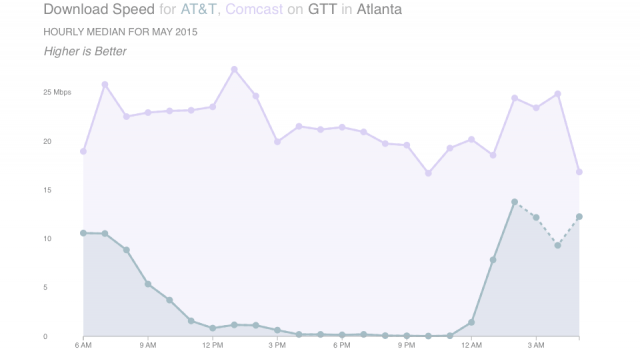

![MLab: "Customers of Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon all saw degraded performance [in NYC] during peak use hours when connecting across transit ISPs GTT and Tata. These patterns were most dramatic for customers of Comcast and Verizon when connecting to GTT, with a low speed of near 1 Mbps during peak hours in May. None of the three experienced similar problems when connecting with other transit providers, such as Internap and Zayo, and Cablevision did not experience the same extent of problems."](https://stopthecap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GTT-tata-640x357.png)

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting.

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting. Cablevision has treated its broadband subscribers to a free speed boost for those signed up for the basic Optimum Online Internet tier. The old speed of 15/5Mbps has today been raised to 25/5Mbps, meeting the FCC’s minimum speed to qualify as broadband service.

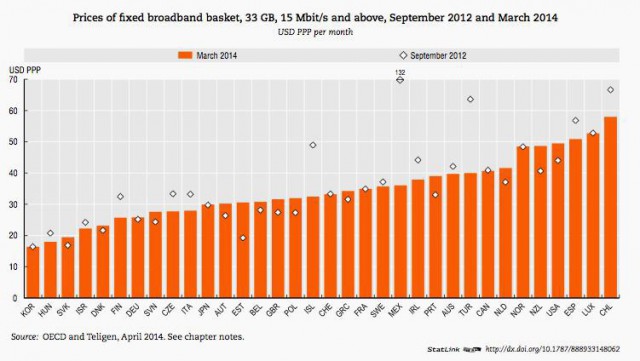

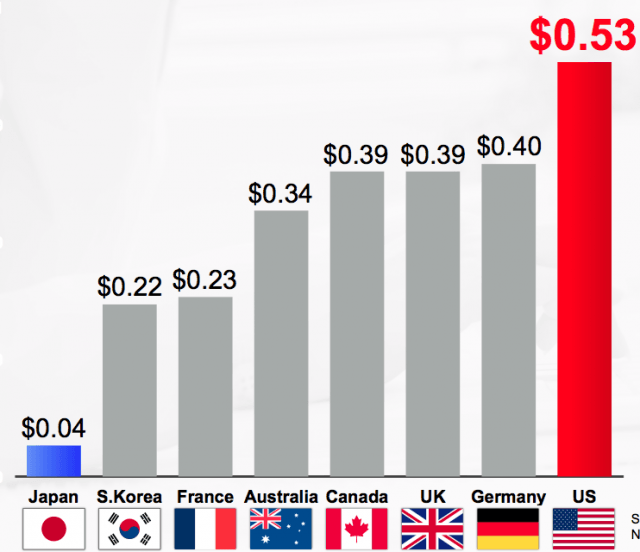

Cablevision has treated its broadband subscribers to a free speed boost for those signed up for the basic Optimum Online Internet tier. The old speed of 15/5Mbps has today been raised to 25/5Mbps, meeting the FCC’s minimum speed to qualify as broadband service. In the last three years, several Wall Street analysts have called on cable and telephone companies to raise the price of broadband service to make up for declining profits selling cable TV. As shareholders pressure executives to keep profits high and costs low, dramatic price changes may be coming for broadband and television service that will boost profits and likely eliminate one of their biggest potential competitors — Sling TV.

In the last three years, several Wall Street analysts have called on cable and telephone companies to raise the price of broadband service to make up for declining profits selling cable TV. As shareholders pressure executives to keep profits high and costs low, dramatic price changes may be coming for broadband and television service that will boost profits and likely eliminate one of their biggest potential competitors — Sling TV.

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment),”

“Our work suggests that cable companies have room to take up broadband pricing significantly and we believe regulators should not oppose the re-pricing (it is good for competition & investment),”  Neither would Sling CEO Roger Lynch, who has a package of 23 cable channels to sell broadband-only customers for $20 a month.

Neither would Sling CEO Roger Lynch, who has a package of 23 cable channels to sell broadband-only customers for $20 a month.