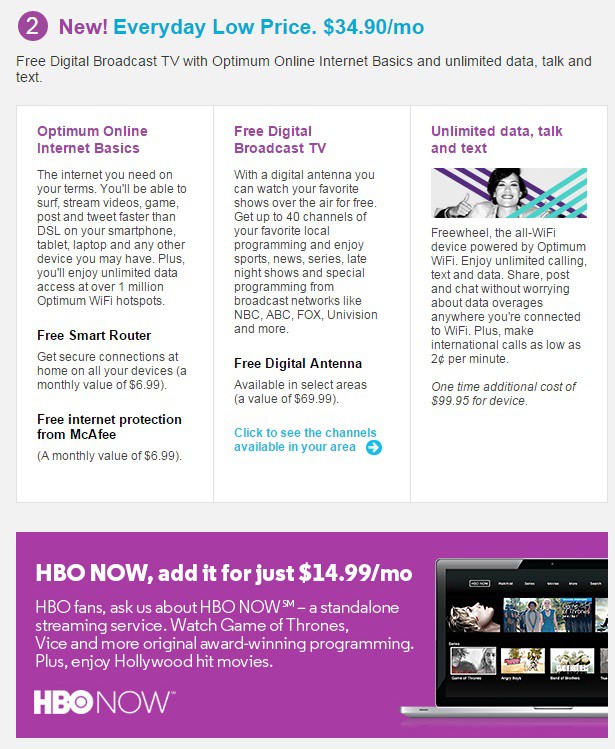

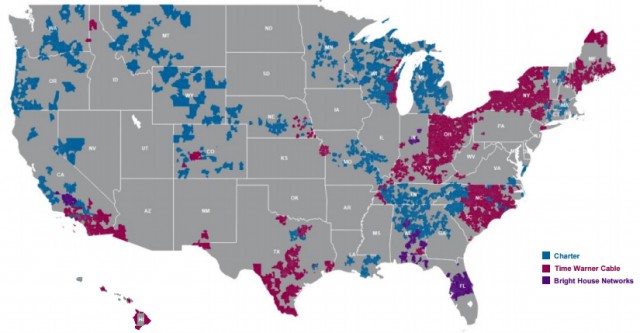

As expected, Charter Communications formally announced its acquisition of Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks in a deal worth, including debt, $78.7 billion.

As expected, Charter Communications formally announced its acquisition of Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks in a deal worth, including debt, $78.7 billion.

The deal brings Dr. John Malone, a cable magnate during the 80s and 90s, back into the top echelon of cable providers. Malone orchestrated today’s deal as part of his plan to dramatically consolidate the American cable industry. Malone’s Liberty Broadband Corp. assisted in pushing the deal across the finish line with an extra $5 billion (supplied by three hedge funds) in Charter stock purchases.

The companies expect to win regulator approval and close the deal by the end of 2015.

“No one has ever had a better sense of the multichannel world than John [Malone],” Leo Hindery, a veteran cable-industry executive, told the Wall Street Journal. “Obviously he sees in Charter and Time Warner Cable a way to perpetuate a legacy that is unrivaled.”

But the man who may have made today’s deal ultimately possible was FCC chairman Tom Wheeler. Last week, he personally called cable executives at Charter and Time Warner Cable to reassure them the FCC was not against all cable mergers just because it rejected one involving Comcast and Time Warner Cable.

But Wheeler warned he would only approve deals that were in the public interest.

“In applying the public interest test, an absence of harm is not sufficient,” Mr. Wheeler said.

Consumer groups are wary.

“The cable platform is quickly becoming America’s local monopoly broadband infrastructure,” said Free Press Research Director S. Derek Turner. “Charter will have a tough time making a credible argument that consolidating local monopoly power on a nationwide basis will benefit consumers. Indeed, the issue of the cable industry’s power to harm online video competition, which is what ultimately sank Comcast’s consolidation plans, are very much at play in this deal.”

“Ultimately, this merger is yet another example of the poor incentives Wall Street’s quarterly-result mentality creates,” Turner added. “Charter would rather take on an enormous amount of debt to pay a premium for Time Warner Cable than build fiber infrastructure, improve service for its existing customers or bring competition into new communities.”

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg Inside the Charter Plan to Buy Time Warner Cable 5-26-15.flv[/flv]

A panel of Wall Street analysts discusses the chances for Charter’s plan to buy Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks. Some analysts continue to frame regulator approval over video programming costs, while others argue broadband is the key issue the FCC and Justice Department will consider when reviewing the merger. From Bloomberg TV. (5:36)

A heavily indebted Charter Communications will not own the combined entity free and clear. At the close of the deal, Time Warner Cable shareholders will own up to 44% of the new company, Liberty Broadband up to 20%, Advance/Newhouse (Bright House) up to 14%. Charter itself will own just 22%, but will be able to leverage voting control over the entity with the help of Malone’s Liberty, which will get almost 25% of the voting power. That will give Charter just enough of a combined edge to control the destiny of “New Charter.”

As with the aborted deal with Comcast, lucrative golden parachutes are expected for Time Warner’s top executives who will be departing if the deal wins approval. In their place will be Charter Communications CEO Thomas Rutledge and a board compromised of 13 directors (including Rutledge himself). Seven directors will be appointed by independent directors serving on Charter’s board, two designated by Advance/Newhouse and three from Liberty Broadband, again giving Rutledge and Malone effective control.

Current Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks customers will see major changes if Charter follows through on its commitment to bring Charter’s way of doing business to both operators.

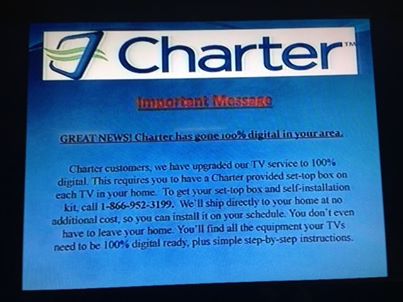

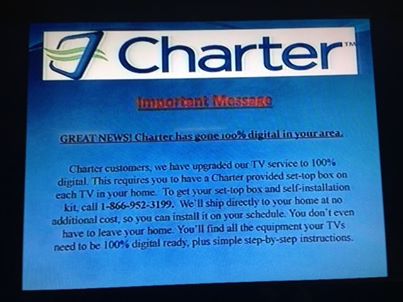

No More Analog Television

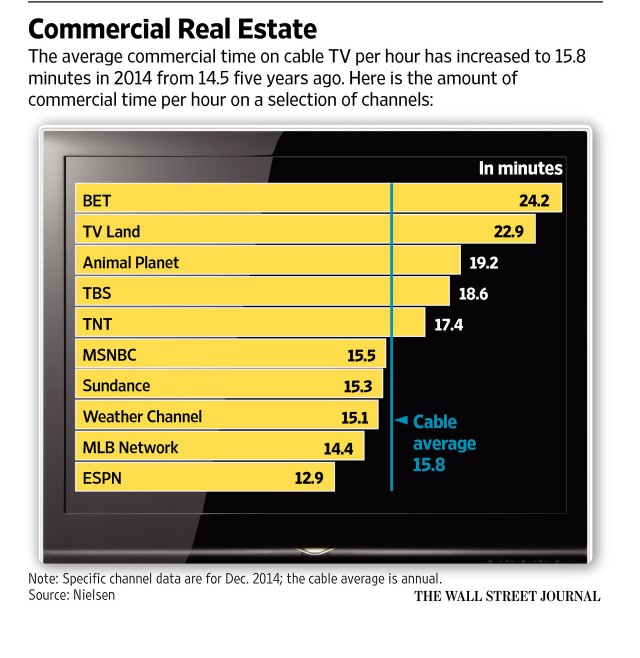

Charter told investors at today’s merger announcement it will accelerate the removal of all analog television signals on TWC and Bright House cable TV lineups to free capacity for faster Internet products, more HD channels, and “other advanced products.”

Charter told investors at today’s merger announcement it will accelerate the removal of all analog television signals on TWC and Bright House cable TV lineups to free capacity for faster Internet products, more HD channels, and “other advanced products.”

Time Warner Cable CEO Rob Marcus told investors earlier this month TWC was already well-positioned with excess spectrum from moving lesser-watched analog channels to digital service and using “Switched Digital Video,” a technology that conserves bandwidth by only sending certain cable channels into neighborhoods where customers are actively watching them. This allowed Time Warner Cable customers to avoid renting a cable box for lesser-watched, cable-connected televisions in the home.

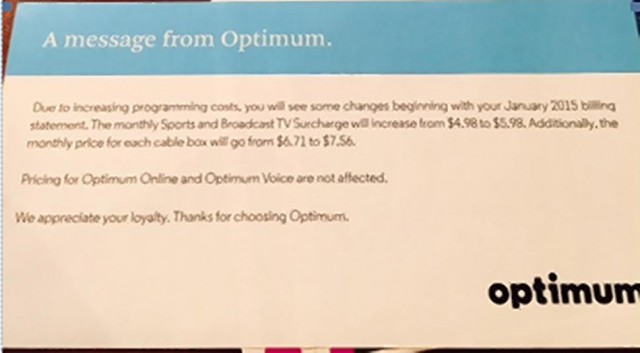

Charter’s plan requires a cable box on every connected television, at an added cost. The standard lease rate for the digital decoder box is $6.99 per month, and those customers on the lowest basic tier will likely receive at least two devices for up to two years for free, or five years for customers on Medicaid. Customers who subscribe to higher tiers of service or premium channels may receive only one device for free for one year before the monthly lease rate applies. For a home with an average of three connected televisions, this will eventually cost an extra $21 a month. DVR boxes cost considerably more.

No More Modem Lease Fee, But Only Two Choices for Internet Service

The good news is Charter does not apply any modem lease fees and there is a good chance if you already purchased your own modem, Charter will continue to let you use it. The bad news is that if you were used to sticking with a lower-speed broadband tier to save money, those days are likely coming to an end. Charter’s “simplified” menu of broadband options cuts Time Warner’s six choices and Bright House’s five options to just two:

- 60/4Mbps for Spectrum Internet ($59.99)

- 100/5Mbps for Internet Ultra ($109.99)

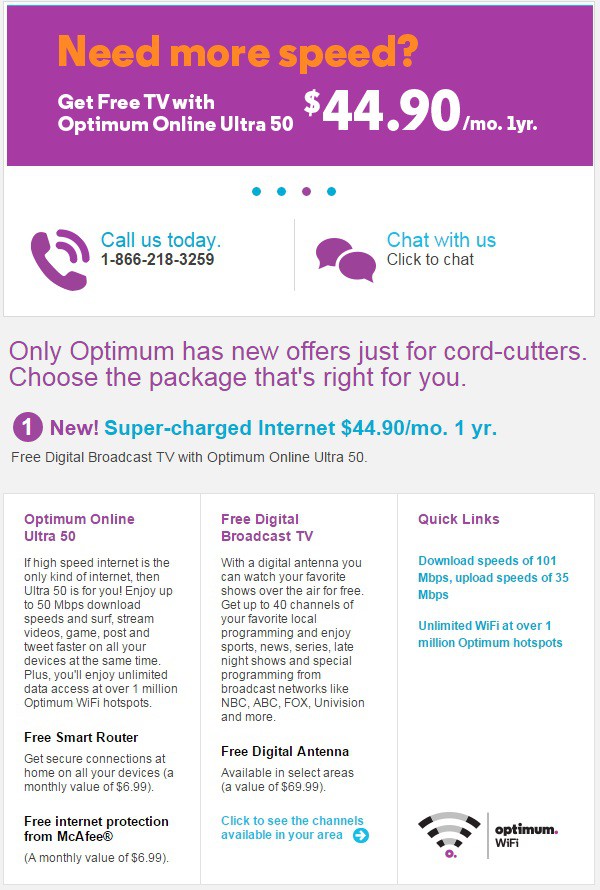

This is likely to be a red flag for regulators concerned about broadband affordability. Although it is likely Charter may offer concessions by grandfathering existing Time Warner Cable and Bright House customers under their current plans, Charter has nothing comparable to Time Warner’s “Everyday Low Price Internet” for $14.99 a month or a 6Mbps Basic broadband alternative far less expensive than Charter’s entry-level Internet tier. Bright House customers are not likely to experience something similar. The entry-level 15Mbps broadband-only plan is $65 a month without a promotion, according to Bright House.

This is likely to be a red flag for regulators concerned about broadband affordability. Although it is likely Charter may offer concessions by grandfathering existing Time Warner Cable and Bright House customers under their current plans, Charter has nothing comparable to Time Warner’s “Everyday Low Price Internet” for $14.99 a month or a 6Mbps Basic broadband alternative far less expensive than Charter’s entry-level Internet tier. Bright House customers are not likely to experience something similar. The entry-level 15Mbps broadband-only plan is $65 a month without a promotion, according to Bright House.

Charter is rumored to be testing speed boosts for those two tiers for deployment in areas where they face fiber competitors. The first phase would raise Spectrum speeds to 100/25Mbps and Ultra to 300/50Mbps with plans to further increase speeds when DOCSIS 3.1 arrives — likely to 300/50Mbps for Spectrum and 500/300 for Ultra, at least where Google Fiber, U-verse with GigaPower, and Verizon FiOS offers competition.

Recently, Charter has followed Time Warner Cable’s marketing script and is actively promoting the fact the company has no data caps on broadband service, but Charter had a history of loosely enforced “soft caps” for several years in the recent past, so we’re not convinced data caps are gone for good at Charter.

Pricing & Service

Charter enjoys a higher rate of revenue per customer than either Time Warner or Bright House, which is a sign customers are paying more. It is likely Charter’s reduced menu of choices is responsible for this. Although customers do get a better advertised level of service, they are paying a higher price for it, with no downgrade options. Ancillary equipment rental fees for television set-top boxes are also a likely culprit.

Charter enjoys a higher rate of revenue per customer than either Time Warner or Bright House, which is a sign customers are paying more. It is likely Charter’s reduced menu of choices is responsible for this. Although customers do get a better advertised level of service, they are paying a higher price for it, with no downgrade options. Ancillary equipment rental fees for television set-top boxes are also a likely culprit.

Charter also tells investors its merger with Time Warner and Bright House will bring “manageable promotional rate step-ups and rate discipline” to both companies. That means Charter will likely be less generous offering promotions to new and existing customers. Like Time Warner and Bright House, Charter will gradually raise rates on customers coming off a promotion until they eventually reset a customer’s rates to the regular price. But while Time Warner, in particular, was receptive to putting complaining customers back on aggressively priced promotions after an old promotion ended, Charter is not.

Charter customers tell us the company’s customer service department is notoriously inconsistent and promotional rates and offers can vary wildly. For some, Charter only got aggressive on price after they turned in their cable equipment and closed their accounts.

As far as service is concerned, CEO Thomas Rutledge has managed significant improvements while at Charter. What used to rival Mediacom in Consumer Reports’ annual ranking of the worst cable companies in America is now ranked number nine (Bright House took fourth place, Time Warner Cable: 12th).

But the presence of Malone in this deal, even peripherally, is a major concern. Malone-run cable companies are notorious for massive rate increases and poor customer service. Sen. Al Gore routinely called his leadership style of Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI), since sold to Comcast, the Darth Vader of a cable Cosa Nostra and Sen. Daniel Inouye from Hawaii once remarked in a Senate oversight hearing that Malone’s executives were a “bunch of thugs.”

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bloomberg Charter CEO Comfortable With Price Paid for Time Warner 5-26-15.flv[/flv]

Watch Charter Communications CEO Thomas Rutledge stumble his way through an answer to a simple question: What are the public benefits of your merger with Time Warner Cable that the deal with Comcast didn’t offer? Did you like his answer? (5:28)

Despite a firm commitment with the Justice Department not to be involved in the day-to-day management of Hulu as a condition of approving Comcast’s merger with NBC/Universal, new revelations suggest Comcast not only promoted the online video service to its partners as a nationwide streaming platform for the cable industry, it also convinced them not to sell the service to a Comcast competitor.

Despite a firm commitment with the Justice Department not to be involved in the day-to-day management of Hulu as a condition of approving Comcast’s merger with NBC/Universal, new revelations suggest Comcast not only promoted the online video service to its partners as a nationwide streaming platform for the cable industry, it also convinced them not to sell the service to a Comcast competitor.

Subscribe

Subscribe On May 15, the last day of this year’s session of the Missouri Legislature,

On May 15, the last day of this year’s session of the Missouri Legislature,

Indeed, when Comcast tried to acquire Time Warner last year, the dominance (nearly 60 percent of the market) that the combined company would have had over broadband service caused federal regulators to look askance. Comcast

Indeed, when Comcast tried to acquire Time Warner last year, the dominance (nearly 60 percent of the market) that the combined company would have had over broadband service caused federal regulators to look askance. Comcast

Charter told investors at today’s merger announcement it will accelerate the removal of all analog television signals on TWC and Bright House cable TV lineups to free capacity for faster Internet products, more HD channels, and “other advanced products.”

Charter told investors at today’s merger announcement it will accelerate the removal of all analog television signals on TWC and Bright House cable TV lineups to free capacity for faster Internet products, more HD channels, and “other advanced products.” This is likely to be a red flag for regulators concerned about broadband affordability. Although it is likely Charter may offer concessions by grandfathering existing Time Warner Cable and Bright House customers under their current plans, Charter has nothing comparable to Time Warner’s “Everyday Low Price Internet” for $14.99 a month or a 6Mbps Basic broadband alternative far less expensive than Charter’s entry-level Internet tier. Bright House customers are not likely to experience something similar. The entry-level 15Mbps broadband-only plan is $65 a month without a promotion, according to Bright House.

This is likely to be a red flag for regulators concerned about broadband affordability. Although it is likely Charter may offer concessions by grandfathering existing Time Warner Cable and Bright House customers under their current plans, Charter has nothing comparable to Time Warner’s “Everyday Low Price Internet” for $14.99 a month or a 6Mbps Basic broadband alternative far less expensive than Charter’s entry-level Internet tier. Bright House customers are not likely to experience something similar. The entry-level 15Mbps broadband-only plan is $65 a month without a promotion, according to Bright House. Charter enjoys a higher rate of revenue per customer than either Time Warner or Bright House, which is a sign customers are paying more. It is likely Charter’s reduced menu of choices is responsible for this. Although customers do get a better advertised level of service, they are paying a higher price for it, with no downgrade options. Ancillary equipment rental fees for television set-top boxes are also a likely culprit.

Charter enjoys a higher rate of revenue per customer than either Time Warner or Bright House, which is a sign customers are paying more. It is likely Charter’s reduced menu of choices is responsible for this. Although customers do get a better advertised level of service, they are paying a higher price for it, with no downgrade options. Ancillary equipment rental fees for television set-top boxes are also a likely culprit.

The deal covers the service’s entire catalog of on-demand television shows and movies and will be available to Cablevision broadband customers online and possibly through set-top boxes for traditional cable television customers.

The deal covers the service’s entire catalog of on-demand television shows and movies and will be available to Cablevision broadband customers online and possibly through set-top boxes for traditional cable television customers.