Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications.

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications.

Working for weeks to settle how Comcast and Charter would divide the second largest cable company in the country between them, they learned about the sudden deal with Comcast the same way the rest of the country heard about it — over Comcast-owned CNBC.

After Charter endured weeks of rejection from Time Warner Cable executives over what they called “a lowball offer,” Comcast had entered the fray to help Charter boost its offer and bring more cash to the table to change Time Warner Cable’s mind. In return, Comcast expected to acquire Time Warner’s east coast cable systems and much more.

That is where the trouble began.

According to Bloomberg News, the talks broke down because Charter wanted to hold onto as many Time Warner Cable assets as possible. Comcast chief financial officer Michael Angelakis expected Charter to divest more than just the New England, New York, and North Carolina Time Warner Cable systems. Angelakis also wanted control of Time Warner’s valuable regional sports networks in Los Angeles. When he didn’t get them, he stormed out of a meeting threatening to do a deal for Time Warner Cable without involving Charter at all.

According to Bloomberg News, the talks broke down because Charter wanted to hold onto as many Time Warner Cable assets as possible. Comcast chief financial officer Michael Angelakis expected Charter to divest more than just the New England, New York, and North Carolina Time Warner Cable systems. Angelakis also wanted control of Time Warner’s valuable regional sports networks in Los Angeles. When he didn’t get them, he stormed out of a meeting threatening to do a deal for Time Warner Cable without involving Charter at all.

The Wall Street Journal confirms the account, adding that both Comcast CEO Brian Roberts and Angelakis agreed the talks with Charter seemed to be going nowhere.

Roberts

Roberts called a secret meeting with top Comcast executives including Angelakis, Comcast Cable head Neil Smit, Comcast’s lobbying heavyweight David Cohen, and NBCUniversal CEO Steven Burke. Roberts asked each about the options on the table and their conclusion was to buy Time Warner Cable by themselves and cut Charter out of the deal.

Within days, Comcast CEO Brian Roberts reinitiated talks with Time Warner Cable CEO Robert Marcus. The two companies had talked off and on ever since Charter Communications set its sights on acquiring Time Warner Cable. It was clear from the beginning Marcus and his predecessor Glenn Britt were cool to Charter’s overtures. Not only was Charter a much smaller operation, it also had a checkered past including a recent bankruptcy that wiped out shareholder value and was loaded with debt again.

The alliance between Charter and Liberty Global’s John Malone was also unsettling. Those in the cable industry had watched how ruthless Malone could be back in the 1990s when a then much-smaller Comcast secretly attempted to acquire control of Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) — then the nation’s largest cable operator run by Malone. Malone was furious when he learned about the effort and went all out to kill the deal, acquiring the stake Comcast sought himself.

Malone’s cable empire would eventually fall with the sale of TCI to AT&T just a few years later. When AT&T decided it didn’t to stay in the cable business, it sold TCI’s old territories to Comcast, making it the largest cable operator in the country.

Malone

Malone’s brash attitude has also occasionally rubbed the cable industry’s kingpins the wrong way, especially in his public comments. Last year, Malone criticized Roberts’ more conservative operating style, which means Comcast pays a higher tax rate. Malone specializes in deals that leave his acquisitions with enormous debt loads, manipulating the tax code to stiff the Internal Revenue Service. In June, Malone was back again criticizing the lack of a unified national cable cartel better positioned to defeat the competition.

Under his leadership at TCI, many cable programmers didn’t get on TCI’s cable dial unless they sold part-ownership to TCI. Competitors were dispatched ruthlessly — home satellite dish service, then the most viable competitor, strained under TCI-led efforts to enforce channel encryption.

TCI-owned networks routinely required satellite subscribers to sign up with the nearest TCI cable system, which often billed them at prices higher than what cable subscribers paid. Subscribers had to buy not one, but eventually two decoder modules for several hundred dollars apiece before they could even purchase programming. The cable industry also worked behind the scenes to promote and defend enhanced zoning laws that made installing satellite dishes difficult if not impossible, and denied access to some programming at any price, unless it was delivered by a cable system.

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Despite Liberty Global’s ongoing consolidation wave of European cable systems, his lack of financial resources to put his money where his mouth was left Time Warner Cable executives cold.

Already loaded with debt, Malone’s part ownership stake in Charter could not make up for Charter’s current status — a medium-sized cable operator with dismal customer ratings primarily serving smaller communities bypassed by larger operators.

A deal with Charter would mean Time Warner Cable’s bonds would be downgraded to junk status.

Moody’s Investor Service warned Charter’s offer to acquire Time Warner Cable was primarily financed with the equivalent of a credit card, and would leave the combined entity with $60 billion in debt with bonds promptly downgraded to junk level. Time Warner Cable had always considered its bonds “investment grade.”

Charter’s first clue something was wrong came when Comcast stopped returning e-mail and phone calls. That’s always cause for alarm, but Charter officials had no idea Comcast was secretly negotiating with Time Warner Cable one-on-one. In fact, Comcast’s Roberts was negotiating with Time Warner Cable over a cell phone while attending the Sochi Olympics.

Malone finally got the word the deal was off just a short while before Comcast and Time Warner Cable leaked the story to CNBC.

Ironically, it was Malone who convinced Comcast to seek out a deal with Time Warner Cable. Comcast’s thinking had originally been it had grown large enough as a cable operator and sought out expansion in the content world, acquiring NBCUniversal. But Malone warned online video competitors like Netflix would begin to give customers a reason to cut cable’s cord or at the very least take their business to AT&T or Verizon’s competing platforms.

Comcast executives were convinced that gaining more control over content and distribution was critical to protect profits. Only with the vast scale of a supersized Comcast could the cable company demand lower prices and more control over programming. By dominating broadband, critics of the deal warn Comcast can also keep subscribers from defecting while charging higher prices for Internet access and imposing usage limits that can drive future revenue even higher.

Just like the “good old days” where customers had to do business with the cable company at their asking price or go without, a upsized Comcast will dominate over satellite television, which cannot offer broadband or phone service, as well as the two largest phone companies — AT&T, which so far cannot compete with Comcast’s broadband speed and Verizon, which has pulled the plug on further expansion of FiOS to divert investment into its highly profitable wireless division. If Comcast controls your Internet connection, it can also control what competitors can effectively offer customers. Even if Comcast agrees to voluntarily subscribe to Open Internet principles like Net Neutrality, its usage cap can go a long way to protect it from online video competitors who rely on cable broadband to deliver HD video in the majority of the country not served by U-verse or FiOS.

Bright House Networks’ long standing relationship with Time Warner Cable — which negotiated programming deals on behalf of the smaller cable operator with operations in the south — may come to an end with an approval of a merger between Comcast and Time Warner. That could make Bright House a prime candidate for a takeover.

Bright House Networks’ long standing relationship with Time Warner Cable — which negotiated programming deals on behalf of the smaller cable operator with operations in the south — may come to an end with an approval of a merger between Comcast and Time Warner. That could make Bright House a prime candidate for a takeover. Charter is almost certain to buy at least some of the three million Time Warner Cable customers Comcast intends to cast-off if it wins regulator approval of its buyout deal. But Team Charter has assembled enough financing to go much farther than that.

Charter is almost certain to buy at least some of the three million Time Warner Cable customers Comcast intends to cast-off if it wins regulator approval of its buyout deal. But Team Charter has assembled enough financing to go much farther than that. Cox, like Cablevision, has been closely controlled by its founding family for years, so rumors of sales of one or both have never come to fruition. But with the merger announcement of Comcast and Time Warner Cable, Wall Street pressure to consolidate is growing by the day. There is talk that if Comcast succeeds in its buyout effort, even satellite providers like DirecTV and DISH are likely to seek a merger. Even Cablevision, which serves suburban New York City may finally feel enough pressure to sell.

Cox, like Cablevision, has been closely controlled by its founding family for years, so rumors of sales of one or both have never come to fruition. But with the merger announcement of Comcast and Time Warner Cable, Wall Street pressure to consolidate is growing by the day. There is talk that if Comcast succeeds in its buyout effort, even satellite providers like DirecTV and DISH are likely to seek a merger. Even Cablevision, which serves suburban New York City may finally feel enough pressure to sell.

Subscribe

Subscribe Earthlink and Time Warner Cable are two independent companies, but you would never know it from Time Warner Cable’s mailed notification of rate increases that will apply to customers of both. In addition to general rate increases, Time Warner is now imposing its $5.99 monthly modem rental charge on Earthlink customers that used to avoid the modem fee.

Earthlink and Time Warner Cable are two independent companies, but you would never know it from Time Warner Cable’s mailed notification of rate increases that will apply to customers of both. In addition to general rate increases, Time Warner is now imposing its $5.99 monthly modem rental charge on Earthlink customers that used to avoid the modem fee. Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications.

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications. According to Bloomberg News, the

According to Bloomberg News, the

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

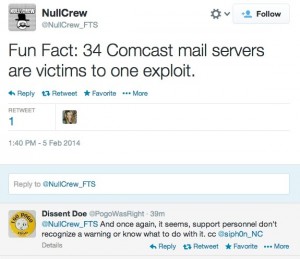

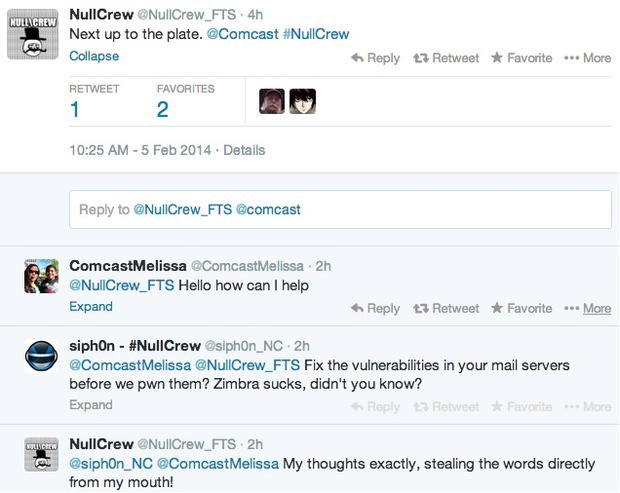

At least 34 of Comcast’s email servers have been compromised by a well-known hacker group that posted evidence, the exploit, and certain administrative passwords online to embarrass the company and expose its poor security practices.

At least 34 of Comcast’s email servers have been compromised by a well-known hacker group that posted evidence, the exploit, and certain administrative passwords online to embarrass the company and expose its poor security practices.

In 2012, Cogeco acquired rural and small city cable operator Atlantic Broadband for $1.36 billion. Atlantic offers service in Pennsylvania, Florida, Maryland, Delaware, and South Carolina — mostly in communities ignored by Comcast and Time Warner Cable.

In 2012, Cogeco acquired rural and small city cable operator Atlantic Broadband for $1.36 billion. Atlantic offers service in Pennsylvania, Florida, Maryland, Delaware, and South Carolina — mostly in communities ignored by Comcast and Time Warner Cable.