David “I’m crushing your head” Cohen

Your boss authorized $32 million on lobbying for a $45 billion dollar merger deal that just went down in flames on your watch and you were the guy the company depended on to push it through. What do you do?

If you are Comcast vice president David Cohen, you pray for a press release signed by the CEO reaffirming trust in you.

Cohen can breathe a little easier because Brian Roberts, CEO of Comcast, did exactly that.

“There is nobody better than David Cohen,” Roberts wrote. “He’s incredible at what he does and we are beyond lucky that he helps passionately lead so many areas at Comcast. He is also a huge supporter of Philadelphia and has done so much for the community. I’m extremely proud to have him on our team.”

It could have been much worse for Cohen, whose contract (and $15 million annual salary) is up at the end of this year. He’s the fourth biggest earner at Comcast, but his stunning arrogance before Congress and the public may have helped nail the coffin shut on a merger worth tens of billions.

Some media outlets have called Cohen myopic, unable to see the building torrent of opposition from consumers, public interest groups, and even regulators.

“They just lost a big battle. Does the company need a new general to supervise the Washington political strategy?” asked one source.

Comcast is already on the hunt for a new chief financial officer, with Michael Angelakis walking away to begin his own Comcast-backed private-equity fund before the deal imploded.

Comcast’s claims of “deal benefits” for consumers was perceived to be tissue-thin by legislators like Rep. Tony Cárdenas (D-Calif.), whose district would have seen Time Warner and Charter customers absorbed into the Comcast Dominion.

Comcast’s claims of “deal benefits” for consumers was perceived to be tissue-thin by legislators like Rep. Tony Cárdenas (D-Calif.), whose district would have seen Time Warner and Charter customers absorbed into the Comcast Dominion.

“[Cohen] was smothering us with attention but he was not answering our questions,” Cárdenas told The New York Times, adding in the early stages of the deal he was open to supporting it if his questions were addressed satisfactorily. “And I could not help but think that this is a $140 billion company with 130 lobbyists — and they are using all of that to the best of their ability to get us to go along.”

Comcast’s swaggering arrogance, condescending editorials, and dismissive attitude towards consumers questioning the deal rubbed a lot of lawmakers the wrong way.

Not only did Comcast offend lawmakers, but their all-important staffers as well. Staffers told the newspaper they felt Comcast was so convinced in the early stages that the deal would be approved that it was dismissing concerns about the transaction, or simply taking the conversation in a different direction when asked about them.

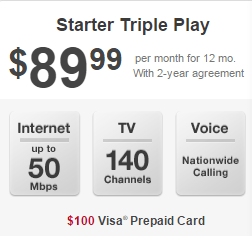

Elected officials associating themselves with Comcast, whose customer service on a good day is considered miserable, was also considered political poison. Few lawmakers were willing to publicly support foisting Comcast on their constituents. Local lawmakers in Time Warner Cable service areas who had no direct experience with Comcast customer service’s special touch of hell often did offer support, especially when a handsome check was sent weeks earlier. But voters with relatives or friends who loathed Comcast (practically everyone in America) were never fooled.

“They talked a lot about the benefits, and how much they were going to invest in Time Warner Cable and improve the service it provided,” said one senior Senate staff aide, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly. “But every time you talked about industry consolidation and the incentive they would have to leverage their market power to hurt competition, they gave us unsatisfactory answers.”

“They talked a lot about the benefits, and how much they were going to invest in Time Warner Cable and improve the service it provided,” said one senior Senate staff aide, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly. “But every time you talked about industry consolidation and the incentive they would have to leverage their market power to hurt competition, they gave us unsatisfactory answers.”

Politicians asked to publicly support the deal characterized their sentiment as “leery” in polite company.

Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) was unwilling to victimize her constituents by replacing two bad cable companies – Time Warner Cable and Charter with one horrible alternative – Comcast.

“No amount of public-interest commitments to diversity would remedy the consumer harm a merged Comcast-Time Warner would have caused to millions of Americans across the country,” Ms. Waters said.

Other lawmakers who already understood Comcast as the Hurricane Katrina of cable companies got into storm shelters early.

“There are limits as to how effective even the best advocate can be with a losing case,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut, who was critical of the deal from the start, “as this merger would have further enhanced this company’s incentive, its means and its history of abuse of market power.”

Comcast even cynically attempted to color and race match lobbyists with legislators, believing the shared ethnic heritage would be an added incentive.

The New York Times:

Comcast, for example, assigned Juan Otero, a former Department of Homeland Security official who serves on the board of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute and now works as a Comcast lobbyist, to be the point person to work with Mr. Cárdenas.

Meanwhile, Jennifer Stewart, an African-American lobbyist on the Congressional Black Caucus Institute board, was assigned to work with Marc Veasey, Democrat of Texas, who is also black. She personally appealed to Mr. Veasey’s staff, urging that he not sign a letter last August questioning the deal, according to an email obtained by The New York Times, citing the company’s work on behalf of the minority community. (Mr. Veasey still signed a related letter.)

Comcast also asked Jordan Goldstein, a former official at the Federal Communications Commission who is now a Comcast regulatory affairs executive, to work with Mr. Blumenthal’s office. Mr. Goldstein had previously developed a working relationship with Joel Kelsey, a legislative assistant in charge of reviewing the matter for the senator, who is a member of the Senate Commerce Committee.

Subscribe

Subscribe Under consideration by the Justice Department:

Under consideration by the Justice Department:

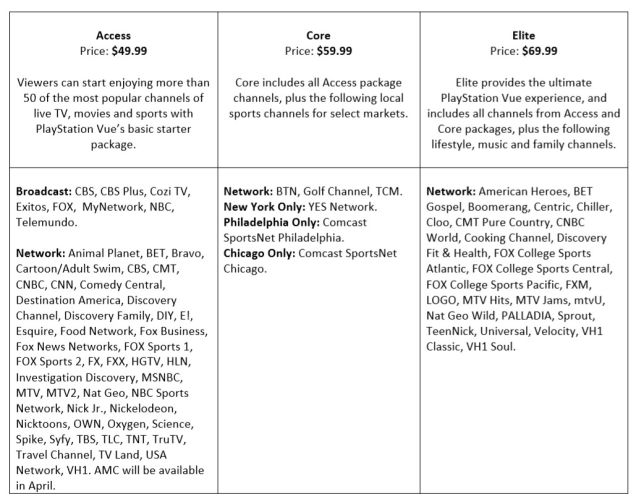

“Hence, we remain cautiously optimistic that cord-cutting, in large numbers, isn’t likely to happen,” Juenger wrote his clients. “It’s one of those ideas that sounds great in the abstract but crumbles when faced with the reality.”

“Hence, we remain cautiously optimistic that cord-cutting, in large numbers, isn’t likely to happen,” Juenger wrote his clients. “It’s one of those ideas that sounds great in the abstract but crumbles when faced with the reality.”

A Pennsylvania attorney that didn’t pay his $215 Comcast bill was hounded by Comcast’s collections crew despite never getting cable service at his new address.

A Pennsylvania attorney that didn’t pay his $215 Comcast bill was hounded by Comcast’s collections crew despite never getting cable service at his new address.