Is your cable television service included in your rent or condo “services” fee? Have you ever called another provider and told service was not available at your address even through others outside of your condo neighborhood or apartment complex can sign up for service today? Chances are your landlord or property management company is receiving a kickback to keep competition off the property, while you may be stuck paying for substandard services you neither want or need. Worst of all, chances are it’s all legal and everyone is getting a piece of the action… except you.

Is your cable television service included in your rent or condo “services” fee? Have you ever called another provider and told service was not available at your address even through others outside of your condo neighborhood or apartment complex can sign up for service today? Chances are your landlord or property management company is receiving a kickback to keep competition off the property, while you may be stuck paying for substandard services you neither want or need. Worst of all, chances are it’s all legal and everyone is getting a piece of the action… except you.

Welcome to the world of Multiple Dwelling Unit (MDU) Bulk Service Agreements, the seedy underbelly of the anti-competitive cable and telco-TV world. When cable TV first got going, most people wanted access. In the early days, cable franchises were typically exclusive and cable companies maintained the upper hand in negotiations with apartment owners and property owners. Since the service was in demand, many property owners were told to sign whatever “Right Of Entry” Agreement (ROE) was put in front of them. Most contained clauses that guaranteed that cable company would get exclusive access to the property for as long as it was given a franchise to operate within that community. In other words, basically forever.

This turned out very handy when competitors started showing up. First on the scene were satellite television providers, which had a rough time dealing with landlords who loathed tenants installing satellite dishes that “ruined the aesthetics” of the property. Many rental agreements still restrict satellite television dishes in ways that make their use untenable. But things got much more serious when Verizon and AT&T got into the cable business. Initially, both companies found extending FiOS and U-verse to some rental and gated communities was blocked by the exclusive agreements held by cable operators. By 2007, the FCC finally acted to forbid exclusive service contracts, but the cable industry and property developers have played cat and mouse games with the FCC’s loopholes ever since.

Property Developers, Management Companies, Landlords, and Homeowner Associations With Their Hands Out

With the FCC’s 2007 declaration that exclusive contracts between cable companies and property owners were “null and void,” the power of the cable industry to negotiate on their terms was markedly diminished. Although many property owners applauded their new-found freedom to tell the local cable company to take a hike if they did not offer better service to their tenants, many others saw dollar signs in their eyes. With leverage now in the hands of the property owner, if the local cable company wanted to stay, in many cases it had to pay. Only the most brazen property owners kicked uncooperative cable companies off their properties, putting tenants at a serious inconvenience. Instead, many found life more peaceful and lucrative to stick with the existing cable company, signing a new contract for “bulk billing” tenants. On the surface, it seemed like a good deal. Property owners advertised that cable TV was included in the rent (and they paid a deeply discounted price per tenant) and the cable operator had a guaranteed number of customers, whether they wanted the service or not.

With the FCC’s 2007 declaration that exclusive contracts between cable companies and property owners were “null and void,” the power of the cable industry to negotiate on their terms was markedly diminished. Although many property owners applauded their new-found freedom to tell the local cable company to take a hike if they did not offer better service to their tenants, many others saw dollar signs in their eyes. With leverage now in the hands of the property owner, if the local cable company wanted to stay, in many cases it had to pay. Only the most brazen property owners kicked uncooperative cable companies off their properties, putting tenants at a serious inconvenience. Instead, many found life more peaceful and lucrative to stick with the existing cable company, signing a new contract for “bulk billing” tenants. On the surface, it seemed like a good deal. Property owners advertised that cable TV was included in the rent (and they paid a deeply discounted price per tenant) and the cable operator had a guaranteed number of customers, whether they wanted the service or not.

Bulk billing also proved a very effective deterrent for would-be competitors, who had to overcome the challenge of marketing their service while the tenant was already paying for another as part of their rent. As a result, telco TV competitors often stayed away from properties with bulk billing arrangements.

As broadband has become more prominent and threatens to become more important than the cable TV package, the cable industry has refined its weapons of non-competition. While they cannot force competitors off properties, they can make life very expensive for them. The latest generation of ROE agreements often grant access rights to the building’s telecommunications conduit, cabling, and equipment exclusively to the cable operator.

If Google Fiber, AT&T U-verse or Verizon FiOS sought to offer service on one of these properties, they would have to overcome the investment insanity of wiring each building with its own infrastructure, including duplicate cables, in separate conduits and spaces not already designated for the exclusive use of the cable company. Verizon in New York City has faced numerous obstacles wiring some buildings, including gaining access to the building itself. Intransigent on site employees, bureaucratic and unresponsive property management companies, and developers have all made life difficult for Verizon’s fiber upgrade.

If Google Fiber, AT&T U-verse or Verizon FiOS sought to offer service on one of these properties, they would have to overcome the investment insanity of wiring each building with its own infrastructure, including duplicate cables, in separate conduits and spaces not already designated for the exclusive use of the cable company. Verizon in New York City has faced numerous obstacles wiring some buildings, including gaining access to the building itself. Intransigent on site employees, bureaucratic and unresponsive property management companies, and developers have all made life difficult for Verizon’s fiber upgrade.

AT&T often takes the approach “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” and offers its own bulk billing incentives, along with occasional commitments for fiber upgrades. Google Fiber can afford to skip places where it isn’t wanted, although with recent revelations that landlords can raise the rent by up to 11% with the arrival of Google Fiber alone, it may hurt to alienate that fiber to the home provider.

Kickbacks for New Developments = Windfall

Kickbacks for existing properties are lucrative, but nothing compared to the lucrative windfall new property developments can achieve with the right deal.

In 2013, one property developer in Maryland went all out for an exclusive deal with a provider that was going to get de facto exclusivity by using a convoluted series of entities and agreements designed to insulate the company from competition and a challenge from the FCC. A court later ruled the provider used an “elaborate game of regulatory subterfuge” using various corporate entities to escape potential competition.

Some lawyers devote a substantial amount of their practice to the issue of bulk contracts and ROE agreements. Carl Kandutsch serves clients nationwide, many trying to extricate themselves from bad deals of the past. In many cases, an attorney may be needed to find a way out of contracts that don’t meet FCC rules. Other communities sometimes have to buy out an existing contract. Many have to sit and suffer the consequences for years. One residential community found itself trapped with a service provider that was quietly protected by an “airtight contract” negotiated not with the property management company or the homeowner association, but the development’s original builder. The provider delivered lousy service and the community spent six years trying to get rid of the offending firm with no result until they hired an attorney. Although happy to be rid of the bad provider, the homeowner association ended up illustrating how pervasive this problem is after it signed a similar contract with another provider also handing out kickbacks.

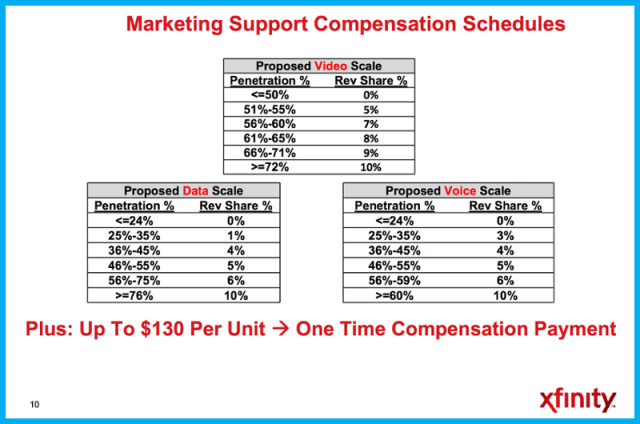

Comcast pays up to 10% of a renter’s cable bill to the landlord. (Image: Susan Crawford)

Comcast is more creative than most. It calls its handouts: “Marketing Support Compensation.” The property owner gets an increasing reward for every tenant signed up for Comcast service. Once around two-thirds of tenants are subscribed, the owner gets up to a 10% take of each bill, plus a one time payment of up to $130 per tenant.

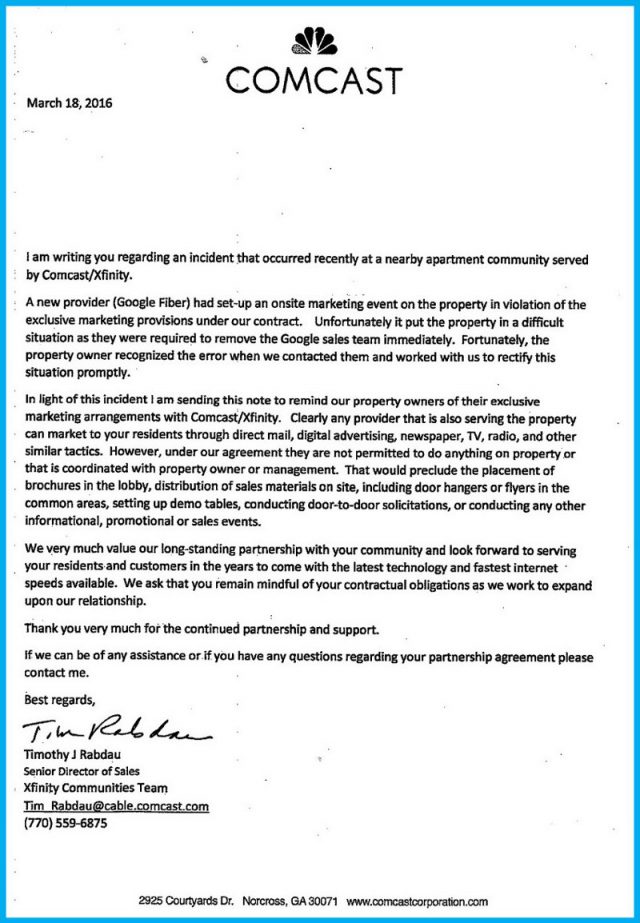

Because Comcast’s reputation often precedes it, customers reluctant to sign up without considering other providers will find that tougher to do because Comcast bans other providers from marketing their services to tenants with the support or cooperation of the landlord. In other words, no door hangers, free coffee, brochures in the lobby, or any other on-site promotions. In case a property owner forgets, Comcast sends reminders in the mail:

Comcast likes to remind landlords it has an exclusive. (Image: Susan Crawford)

Susan Crawford calls it “astounding, enormous, decentralized payola” and claims it affects millions of renters.

Crawford

“These shenanigans will only stop when cities and national leaders require that every building have neutral fiber/wireless facilities that make it easy for residents to switch services when they want to,” Crawford wrote. “We’ve got to take landlords out of the equation — all they’re doing is looking for payments and deals (understandably: they’re addicted to the revenue stream they’ve been getting), and the giant telecom providers in our country are more than happy to pay up. The market is stuck. Residents have little idea these deals are happening. The current way of doing business is great for landlords and ISPs but destructive in every other way.”

One real world example of how this deters competition comes from Webpass (recently acquired by Google), which offers gigabit Ethernet speeds in select MDUs in San Francisco, San Diego, Miami, Chicago, and Boston. The service comes with a low price, but that doesn’t get the company in the door, according to its president, Charles Barr.

Barr has been refused entry by multiple building owners who have agreements with Comcast, AT&T, or others.

“Tenants want us, but we can’t get in,” Barr said.

Crawford argues the FCC has once again been outmaneuvered by ISPs and their attorneys.

“Sure, a landlord can’t enter into an exclusive agreement granting just one ISP the right to provide Internet access service to an MDU, but a landlord can refuse to sign agreements with anyone other than Big Company X, in exchange for payments labeled in any one of a zillion ways,” added Crawford. “Exclusivity by any other name still feels just as abusive.”

This isn’t a new problem. Stop the Cap! first reported on these kinds of bulk buying arrangements back in 2010, all made possible by the FCC’s regulatory loopholes. Six years later, the problem appears to be getting worse.

Subscribe

Subscribe

“I think it’s vital to put our country’s well being ahead of party,” he said in a statement provided by the Clinton campaign. “Hillary Clinton is experienced, qualified, and will make a fine president. The alternative, I fear, would set our nation on a very dark path.”

“I think it’s vital to put our country’s well being ahead of party,” he said in a statement provided by the Clinton campaign. “Hillary Clinton is experienced, qualified, and will make a fine president. The alternative, I fear, would set our nation on a very dark path.” Cicconi would be pleased to see someone like former Tennessee congressman Harold Ford, Jr., take a seat at the FCC under a future Clinton Administration instead. Ford has served as an honorary co-chairman of Broadband for America, an industry-sponsored astroturf operation, for most of Obama’s two terms in office. He remains a close friend of both Bill and Hillary and is never far from the public eye, turning up regularly on MSNBC.

Cicconi would be pleased to see someone like former Tennessee congressman Harold Ford, Jr., take a seat at the FCC under a future Clinton Administration instead. Ford has served as an honorary co-chairman of Broadband for America, an industry-sponsored astroturf operation, for most of Obama’s two terms in office. He remains a close friend of both Bill and Hillary and is never far from the public eye, turning up regularly on MSNBC.

“Sharing is essential for the future of spectrum utilization. Many of the high-frequency bands we will make available for 5G currently have some satellite users, and some federal users, or at least the possibility of future satellite and federal users,” Wheeler noted. “This means sharing will be required between satellite and terrestrial wireless; an issue that is especially relevant in the 28GHz band. It is also a consideration in the additional bands we will identify for future exploration. We will strike a balance that offers flexibility for satellite users to expand, while providing terrestrial licensees with predictability about the areas in which satellite will locate.”

“Sharing is essential for the future of spectrum utilization. Many of the high-frequency bands we will make available for 5G currently have some satellite users, and some federal users, or at least the possibility of future satellite and federal users,” Wheeler noted. “This means sharing will be required between satellite and terrestrial wireless; an issue that is especially relevant in the 28GHz band. It is also a consideration in the additional bands we will identify for future exploration. We will strike a balance that offers flexibility for satellite users to expand, while providing terrestrial licensees with predictability about the areas in which satellite will locate.”

Time Warner Cable customers getting inundated with ads promising great things from Charter’s buyout of Time Warner Cable have their first broken promise from “Spectrum” to contend with instead.

Time Warner Cable customers getting inundated with ads promising great things from Charter’s buyout of Time Warner Cable have their first broken promise from “Spectrum” to contend with instead. The internal Time Warner Cable memo, now confirmed as genuine by Time Warner, suggests the hold is temporary, but sources tell us Charter executives are reviewing expenses across the board to find cost saving opportunities. Most states approving the transaction gave Charter plenty of room to maneuver while approving its merger deal because of Charter’s considerably less aggressive upgrade schedule, in comparison to Time Warner Cable. Few states asked Charter for anything more than what Charter volunteered itself.

The internal Time Warner Cable memo, now confirmed as genuine by Time Warner, suggests the hold is temporary, but sources tell us Charter executives are reviewing expenses across the board to find cost saving opportunities. Most states approving the transaction gave Charter plenty of room to maneuver while approving its merger deal because of Charter’s considerably less aggressive upgrade schedule, in comparison to Time Warner Cable. Few states asked Charter for anything more than what Charter volunteered itself.