Western New York

In a recent survey of 2,000 residents living in Erie County (Buffalo), N.Y., it was clear almost nobody trusts their internet service provider, and 71% were dissatisfied with their internet service.

Seventeen years after many western New York residents heard the word “broadband” for the first time at a 2000 CNN town hall at the University of Buffalo, where then U.S. Senate candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton called for increased federal funding for high-speed internet, many upstate residents are still waiting for faster access.

The Buffalo News featured two stories about the current state of the internet in western New York and found it lacking.

Erie County Executive Mark C. Poloncarz blames internet service providers for serving up mediocre broadband, and no service at all in some parts of the county he represents.

“It’s been put in the hands of the private sector, and the private sector has, for whatever reason, elected to not expand into particular areas or not increase speeds in particular areas, putting those areas behind the eight ball,” he said.

Poloncarz effectively fingers the three dominant internet providers serving upstate New York – phone companies Verizon and Frontier and cable company Charter/Spectrum. He argues that companies will not even consider locating operations in areas lacking the most modern high-speed broadband. The digital economy is essential to help the recovery of western New York cities affected by the loss of manufacturing jobs and the ongoing departure of residents to other states.

Poloncarz

An important part of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s statewide broadband improvement initiative is prodding Charter Communications and its predecessor Time Warner Cable to do a better job offering faster internet speeds and more rural broadband expansion. The New York Public Service Commission, as part of its approval of Charter’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable, extracted more concessions from the cable giant than any other state. Among them is a commitment to expand the cable company’s footprint into adjacent unserved areas by 2020 to reach at least 145,000 homes and businesses now outside of Charter’s service area.

Last week, the cable company told the PSC it was ahead of schedule on its expansion commitment, now reaching 42,889 additional households and businesses, which is above its goal of 36,771. It has two years left to add at least another 102,111 buildings.

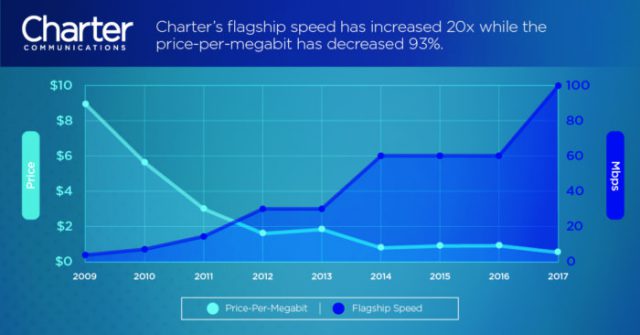

Charter also recently increased broadband speeds to 100 Mbps for 99% of its customers in New York and has committed to boosting those speeds to 300 Mbps by the end of next year.

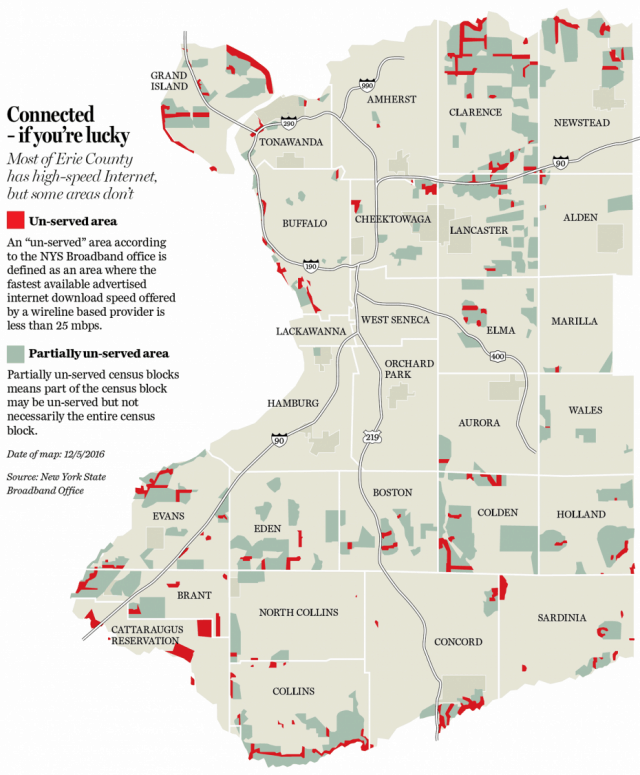

But where Charter does not provide service, broadband problems come courtesy of western New York’s biggest phone companies – Verizon and Frontier. In Erie County, a broadband census found a lack of service in parts of South Buffalo, the far West Side and East Side of Buffalo, as well as in parts of every town in the county except in the prosperous communities of West Seneca and Orchard Park. Verizon FiOS can be found in a handful of well-to-do Buffalo suburban towns, but not in the city itself or in rural parts of the region.

Verizon spokesman Chris McCann said the company had no further plans to expand FiOS service in upstate New York, and stopped announcing additional expansions in 2010. In the rest of its service area, Verizon supplies DSL service as an afterthought, and has made no significant investments to improve or expand service. Frontier Communications, which is the dominant phone company in the greater Rochester region, also provides service in some other rural western New York communities, but its DSL service rarely meets the FCC’s minimum speed definition to qualify as broadband.

Rep. Collins

Both phone companies have no plans for significant fiber optic upgrades that would boost internet speeds. There is little pressure on either company to begin costly upgrades. In rural communities, both companies lack cable competition and in more urban areas, both have written off their ongoing customer losses to their cable competitor. That leaves towns like North Collins in a real dilemma. Poloncarz told the newspaper residents frequently park in the town library parking lot at night to connect to the library’s Wi-Fi service, because they lack internet service at home.

A political divide has opened up between area Democrats and Republican officials on how to solve the rural broadband problem. Democrats like Poloncarz are exploring solving the rural internet problem with a county-owned fiber network that would be open to all private ISPs to assist them in expanding service. He is joined by Erie County legislator Patrick Burke, who thinks it is time to spend the estimated $16.3 million it will take to build an “open access network” across Erie County.

“There are literally geographic dead zones, and it’s unnecessary,” said Burke, a Buffalo Democrat. “There’s no excuse.”

Poloncarz is more cautious and told the newspaper he will only propose the idea if he is convinced it will solve the problem, but is willing to continue studying it.

Republicans from the western New York congressional delegation believe deregulation and other incentives may give private companies enough reasons to begin upgrades and expansion.

Rep. Chris Collins, a Clarence-area congressman with close ties to the Trump White House, defended FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s recent decision to eliminate net neutrality. Pai was born in Buffalo.

Rep. Chris Collins, a Clarence-area congressman with close ties to the Trump White House, defended FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s recent decision to eliminate net neutrality. Pai was born in Buffalo.

Collins argues net neutrality only raised the cost of business for ISPs, and being rid of it would inspire cable and phone companies to boost investment in 105 exurban and rural towns in his district, which covers eight counties and extends from the Buffalo suburbs east to Canandaigua, 80 miles away. More than 65% of those areas are under-served because DSL is often the only choice, and at least 3.3% had no internet options at all.

Rep. Tom Reed (R-Corning) has just as many internet dead zones in his district, if not more. Reed represents the Southern Tier region of western New York in a district that runs along the Pennsylvania border from the westernmost part of New York east nearly to Binghamton. Much of recent broadband development in this part of New York comes as a result of Gov. Cuomo’s state-funded broadband expansion initiative, not private investment.

Reed has a record in Congress that is better at explaining the rural broadband dilemma than solving it.

“In a rural district, there are areas that are just physically difficult to serve,” Reed shrugged.

Collins’ hope that the banishment of net neutrality will inspire Frontier, Verizon, and Charter to use their own money to expand into the frontiers of western New York seems unlikely. Gov. Cuomo’s plan, which uses public funds to help subsidize mostly private companies to expand into areas where Return On Investment fails to meet their metrics has had more success.

But the rural broadband debate has been accompanied by a fierce pushback among upstate New Yorkers against the Republican-controlled FCC and elected officials like Collins who support the recent gutting of net neutrality. A backlash has developed in his district, and some have accused Collins of aiding and abetting a corporate takeover of the internet.

“The hysteria and narrative that this will kill the internet is blatantly false,” responded Collins. “Internet service providers have said they do not increase speeds for certain websites over others, and I have signed onto legislation that would make such a practice illegal.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Just shy of 10 years after FairPoint Communications acquired Verizon’s landline properties in the northern New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, both the company and its name are disappearing forever.

Just shy of 10 years after FairPoint Communications acquired Verizon’s landline properties in the northern New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, both the company and its name are disappearing forever. By early 2016, executives claimed their “turnaround” plan for FairPoint had made significant strides. By that summer, activist shareholders were demanding FairPoint be put up for sale, in part to allow them to quickly recoup their investments in company debt that could not be monetized unless another company acquired FairPoint and assumed those debts.

By early 2016, executives claimed their “turnaround” plan for FairPoint had made significant strides. By that summer, activist shareholders were demanding FairPoint be put up for sale, in part to allow them to quickly recoup their investments in company debt that could not be monetized unless another company acquired FairPoint and assumed those debts. Promised broadband upgrades from speed increases come with few details, except a broad commitment to raise speeds for 300,000 internet customers over the course of this year — which represents about 30% of FairPoint customers. Spokeswoman Angelynne Amores claims there will be no price hikes for faster internet speeds.

Promised broadband upgrades from speed increases come with few details, except a broad commitment to raise speeds for 300,000 internet customers over the course of this year — which represents about 30% of FairPoint customers. Spokeswoman Angelynne Amores claims there will be no price hikes for faster internet speeds. [

[