AT&T was unhappy with the low internet speed score the FCC was about to give the telecom giant, so it made a few phone calls and got the government regulator to effectively rig the results in its favor.

AT&T was unhappy with the low internet speed score the FCC was about to give the telecom giant, so it made a few phone calls and got the government regulator to effectively rig the results in its favor.

“Regulatory capture” is a term becoming more common in administrations that enable regulators that favor friendly relations with large companies over consumer protection, and under the Trump Administration, a very business-friendly FCC has demonstrated it is prepared to go the distance for some of the country’s largest telecom companies.

Today, the Wall Street Journal reported AT&T successfully got the FCC to omit DSL speed test results from the agency’s annual “Measuring Broadband America” report. Introduced during the Obama Administration, the internet speed analysis was designed to test whether cable and phone companies are being honest about delivering the broadband speed they advertise. Using a small army of test volunteers that host a free speed testing router in their home (full disclosure: Stop the Cap! is a volunteer host), automated testing of broadband performance is done silently by the equipment on an ongoing basis, with results sent to SamKnows, an independent company contracted to manage the data for the FCC’s project.

In 2011, the first full year of the program, results identified an early offender — Cablevision/Optimum, which advertised speed it couldn’t deliver to many of its customers because its network was oversold and congested. Within months, the company invested millions to dramatically expand internet capacity and speeds quickly rose, sometimes beyond the advertised level. In general, fiber and cable internet providers traditionally deliver the fastest and most reliable internet speed. Phone companies selling DSL service usually lag far behind in the results. One of those providers happened to be AT&T.

In the last year, the Journal reports AT&T successfully appealed to the FCC to keep its DSL service’s speed performance out of the report and withheld important information from the FCC required to validate some of the agency’s results.

The newspaper also found multiple potential conflicts of interest in both the program and SamKnows, its contracted partner:

- Providers get the full names of customers using speed test equipment, and some (notably Cablevision/Optimum) regularly give speed test customers white glove treatment, including prioritized service, performance upgrades and extremely fast response times during outages that could affect the provider’s speed test score. Jack Burton, a former Cablevision engineer said “there was an effort to make sure known [users] had up-to-date equipment” like modems and routers. Cablevision also marked as “high priority” the neighborhoods that contained speed-testing users, ensuring that those neighborhoods got upgraded ahead of others, said other former Cablevision engineers close to the effort.

- Providers can tinker with the raw data, including the right to exclude results from speed test volunteers subscribed to an “unpopular” speed tier (usually above 100 Mbps), those using outdated or troublesome equipment, or are signed up to an “obsolete” speed plan, like low-speed internet. Over 25% of speed test results (presumably unfavorable to the provider) were not included in the last annual report because cable and phone companies objected to their inclusion.

- SamKnows sells providers immediate access to speed test data and the other data volunteers measure for a fee, ostensibly to allow providers to identify problems on their networks before they end up published in the FCC’s report. Critics claim this gives providers an incentive to give preferential treatment to customers with speed testing equipment.

Some have claimed internet companies have gained almost total leverage over the FCC speed testing project.

The Journal:

Internet experts and former FCC officials said the setup gives the internet companies enormous leverage. “How can you go to the party who controls the information and say, ‘please give me information that may implicate you?’ ” said Tom Wheeler, a former FCC chairman who stepped down in January 2017. Jim Warner, a retired network engineer who has helped advise the agency on the test for years, told the FCC in 2015 that the rules for providers were too lax. “It’s not much of a code of conduct,” Mr. Warner said.

An FCC spokesman told the Journal the program has a transparent process and that the agency will continue to enable it “to improve, evolve, and provide meaningful results as we move forward.”

An FCC spokesman told the Journal the program has a transparent process and that the agency will continue to enable it “to improve, evolve, and provide meaningful results as we move forward.”

The stakes of the FCC’s speed tests are enormous for providers, now more reliant than ever on the highly profitable broadband segment of their businesses. They also allow providers to weaponize favorable performance results to fight off consumer protection efforts that attempt to hold providers accountable for selling internet speeds undelivered. In some high stakes court cases, the FCC’s speed test reports have been used to defend providers, such as the lawsuit filed by New York’s Attorney General against Charter Communications over the poor performance of Time Warner Cable. The parties eventually settled that case.

In 2018, the key takeaway from the report celebrated by providers in testimony, marketing, and lobbying, was that “for most of the major broadband providers that were tested, measured download speeds were 100% or better of advertised speeds during the peak hours.”

Comcast often refers to the FCC’s results in claims about XFINITY internet service: “Recent testing performed by the FCC confirms that Comcast’s broadband internet access service is one of the fastest, most reliable broadband services in the United States.” But in 2018, Comcast also successfully petitioned to FCC to exclude speed test results from 214 of its testing customers, the highest number surveyed among individual providers. In contrast, Charter got the FCC to ignore results from 148 of its customers, Mediacom asked the FCC to ignore results from 46 of its internet customers.

Among the most remarkable findings uncovered by the Journal was the revelation AT&T successfully got the FCC to exclude all of its DSL customers’ speed test results, claiming that it would not be proper to include data for a service no longer being marketed to customers. AT&T deems its DSL service “obsolete” and no longer worthy of being covered by the FCC. But the company still actively markets DSL to prospective customers. This year, AT&T also announced it was no longer cooperating with SamKnows and its speed test project, claiming AT&T has devised a far more accurate speed testing project itself that it intends to use to self-report customer speed testing data.

Cox also managed to find an innovative way out of its poor score for internet speed consistency, which the FCC initially rated a rock bottom 37% of what Cox advertises. Cox claimed its speed test results were faulty because SamKnows’ tests sent traffic through an overcongested internet link yet to be upgraded. That ‘unfairly lowered Cox’s ratings’ for many of its Arizona customers, the company successfully argued, and the FCC put Cox’s poor speed consistency rating in a fine print footnote, which included both the 37% rating and a predicted/estimated reliability rating of 85%, assuming Cox properly routed its internet traffic.

Cox also managed to find an innovative way out of its poor score for internet speed consistency, which the FCC initially rated a rock bottom 37% of what Cox advertises. Cox claimed its speed test results were faulty because SamKnows’ tests sent traffic through an overcongested internet link yet to be upgraded. That ‘unfairly lowered Cox’s ratings’ for many of its Arizona customers, the company successfully argued, and the FCC put Cox’s poor speed consistency rating in a fine print footnote, which included both the 37% rating and a predicted/estimated reliability rating of 85%, assuming Cox properly routed its internet traffic.

The FCC report also downplays or doesn’t include data about internet slowdowns on specific websites, like Netflix or YouTube. Complaints about buffering on both popular streaming sites have been regularly cited by angry customers, but the FCC’s annual report signals there is literally nothing wrong with most providers.

Providers still fear their own network slowdowns or problems during known testing periods. The Journal reports many have a solution for that problem as well — temporarily boosting speeds and targeting better performance of popular websites and services during testing periods and returning service to normal after tests are finished.

James Cannon, a longtime cable and telecom engineering executive who left Charter in February admitted that is standard practice at Spectrum.

James Cannon, a longtime cable and telecom engineering executive who left Charter in February admitted that is standard practice at Spectrum.

“I know that goes on,” he told the Journal. “If they have a scheduled test with a government agency, they will be very careful about how that traffic is routed on the network.”

As a result, the FCC’s “independent” annual speed test report is now compromised by large telecom companies, admits Maurice Dean, a telecom and media consultant with 22 years’ experience working on streaming, cable and telecom projects.

“It is problematic,” Dean said. “This attempt to ‘enhance’ performance for these measurements is a well-known practice in the industry,’ and makes the FCC results “almost meaningless for describing actual user experience.”

Tim Wu, a longtime internet advocate, likened the speed test program as more theoretical than actual, suggesting it was like measuring the speed of a car after getting rid of traffic.

Subscribe

Subscribe Comcast and Charter Communications have begun to compete outside of their respective cable footprints, potentially competing directly head to head for your business, but only if you are a super-sized corporate client.

Comcast and Charter Communications have begun to compete outside of their respective cable footprints, potentially competing directly head to head for your business, but only if you are a super-sized corporate client.

But neither company wants to end their comfortable fiefdoms in the residential marketplace by competing head to head for customers. Companies claim it would not be profitable to install redundant, competing networks, even though independent fiber to the home overbuilders have been doing so in several cities for years. It seems more likely cable operators are deeply concerned about threatening their traditional business model supplying services that face little competition. In the early years, that was cable television. Today it is broadband. Large swaths of the country remain underserved by telephone companies that have decided upgrading their deteriorating copper wire networks to supply residential fiber broadband service is not worth the investment, leaving most internet connectivity in the hands of a single local cable operator. Most cable companies have taken full advantage of this de facto monopoly by regularly raising prices despite the fact that the costs associated with providing internet service have been declining for years.

But neither company wants to end their comfortable fiefdoms in the residential marketplace by competing head to head for customers. Companies claim it would not be profitable to install redundant, competing networks, even though independent fiber to the home overbuilders have been doing so in several cities for years. It seems more likely cable operators are deeply concerned about threatening their traditional business model supplying services that face little competition. In the early years, that was cable television. Today it is broadband. Large swaths of the country remain underserved by telephone companies that have decided upgrading their deteriorating copper wire networks to supply residential fiber broadband service is not worth the investment, leaving most internet connectivity in the hands of a single local cable operator. Most cable companies have taken full advantage of this de facto monopoly by regularly raising prices despite the fact that the costs associated with providing internet service have been declining for years. AT&T was unhappy with the low internet speed score the FCC was about to give the telecom giant, so it made a few phone calls and got the government regulator to effectively rig the results in its favor.

AT&T was unhappy with the low internet speed score the FCC was about to give the telecom giant, so it made a few phone calls and got the government regulator to effectively rig the results in its favor. An FCC spokesman told the Journal the program has a transparent process and that the agency will continue to enable it “to improve, evolve, and provide meaningful results as we move forward.”

An FCC spokesman told the Journal the program has a transparent process and that the agency will continue to enable it “to improve, evolve, and provide meaningful results as we move forward.” Cox also managed to find an innovative way out of its poor score for internet speed consistency, which the FCC initially rated a rock bottom 37% of what Cox advertises. Cox claimed its speed test results were faulty because SamKnows’ tests sent traffic through an overcongested internet link yet to be upgraded. That ‘unfairly lowered Cox’s ratings’ for many of its Arizona customers, the company successfully argued, and the FCC put Cox’s poor speed consistency rating in a fine print footnote, which included both the 37% rating and a predicted/estimated reliability rating of 85%, assuming Cox properly routed its internet traffic.

Cox also managed to find an innovative way out of its poor score for internet speed consistency, which the FCC initially rated a rock bottom 37% of what Cox advertises. Cox claimed its speed test results were faulty because SamKnows’ tests sent traffic through an overcongested internet link yet to be upgraded. That ‘unfairly lowered Cox’s ratings’ for many of its Arizona customers, the company successfully argued, and the FCC put Cox’s poor speed consistency rating in a fine print footnote, which included both the 37% rating and a predicted/estimated reliability rating of 85%, assuming Cox properly routed its internet traffic. James Cannon, a longtime cable and telecom engineering executive who left Charter in February admitted that is standard practice at Spectrum.

James Cannon, a longtime cable and telecom engineering executive who left Charter in February admitted that is standard practice at Spectrum. T-Mobile is gradually expanding its new fixed wireless home broadband service, prioritizing rural areas next to major highways where the mobile provider has strong 4G LTE service.

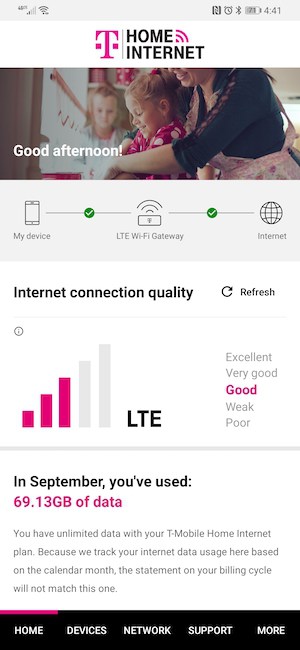

T-Mobile is gradually expanding its new fixed wireless home broadband service, prioritizing rural areas next to major highways where the mobile provider has strong 4G LTE service.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) wants every West Virginian to test their internet speed and send his office the results to ferret out deceptive service maps and uncover more information about the state’s ongoing broadband problems.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) wants every West Virginian to test their internet speed and send his office the results to ferret out deceptive service maps and uncover more information about the state’s ongoing broadband problems.