A research report sponsored by the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, the nation’s largest cable lobbying group, has concluded that millions of broadband stimulus dollars are being wasted by the government on broadband projects that will ultimately serve people who supposedly already enjoy a panoply of broadband choice.

A research report sponsored by the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, the nation’s largest cable lobbying group, has concluded that millions of broadband stimulus dollars are being wasted by the government on broadband projects that will ultimately serve people who supposedly already enjoy a panoply of broadband choice.

Navigant Economics, a “research group” that produces reports for its paying clients inside industry, government, and law firms, produced this one at the behest of a cable industry concerned that broadband stimulus funding will build competing broadband providers that could force better service and lower prices for consumers.

- More than 85 percent of households in the three project areas are already passed by existing cable broadband, DSL, and/or fixed wireless broadband providers. In one of the project areas, more than 98 percent of households are already passed by at least one of these modalities.

- In part because a large proportion of project funds are being used to provide duplicative service, the cost per incremental (unserved) household passed is extremely high. When existing mobile wireless broadband coverage is taken into account, the $231.7 million in RUS funding across the three projects will provide service to just 452 households that currently lack broadband service.

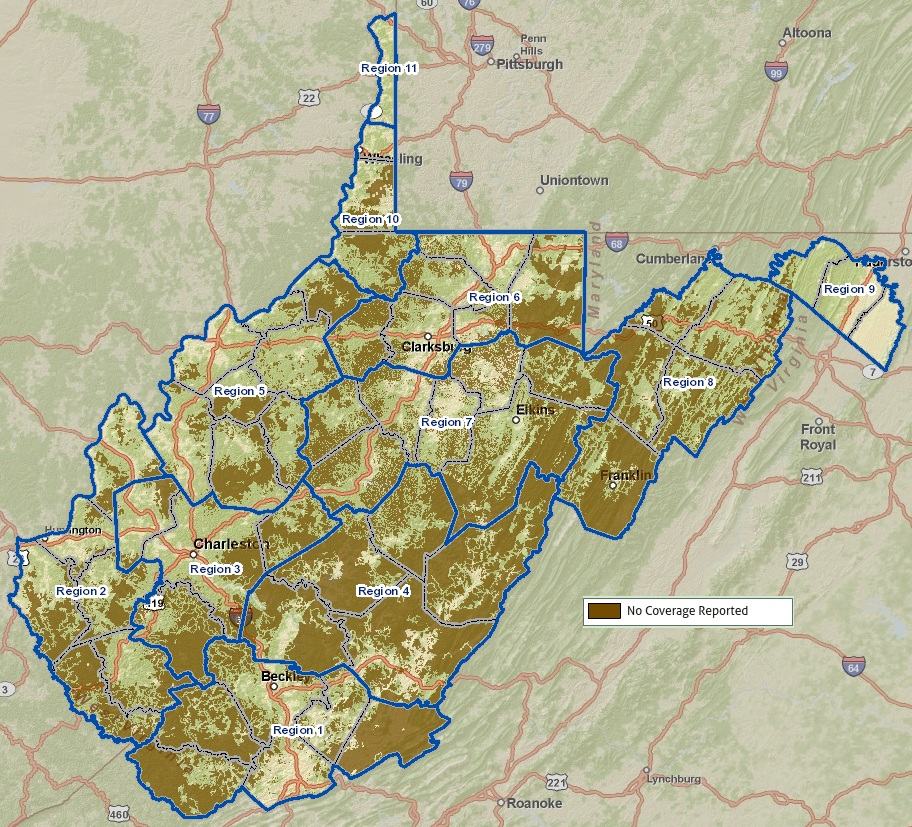

Navigant’s report tries to prove its contention by analyzing three broadband projects that seek funding from the federal government. Northeastern Minnesota, northwestern Kansas, and southwestern Montana were selected for Navigant’s analysis, and unsurprisingly the researcher found the broadband unavailability problem overblown.

The evidence demonstrates that broadband service is already widely available in each of the three proposed service areas. Thus, a large proportion of each award goes to subsidize broadband deployment to households and regions where it is already available, and the taxpayer cost per unserved household is significantly higher than the taxpayer cost per household passed.

The cable industry funds research reports that oppose fiber broadband stimulus projects.

But Navigant’s findings take liberties with what defines appropriate broadband service in the 21st century.

First, Navigant argues that wireless mobile broadband is suitable to meet the definition of broadband service, despite the fact most rural areas face 3G broadband speeds that, in real terms, are below the current definition of “broadband” (a stable 768kbps or better — although the FCC supports redefining broadband to speeds at or above 3-4Mbps). As any 3G user knows, cell site congestion, signal quality, and environmental factors can quickly reduce 3G speeds to less than 500kbps. When was the last time your 3G wireless provider delivered 768kbps or better on a consistent basis?

Navigant also ignores the ongoing march by providers to establish tiny usage caps for wireless broadband. With most declaring anything greater than 5GB “abusive use,” and some limiting use to less than half that amount, a real question can be raised about whether mobile broadband, even at future 4G speeds, can provide a suitable home broadband replacement.

Second, Navigant’s list of available providers assumes facts not necessarily in evidence. For example, in Lake County, Minnesota, Navigant assumes DSL availability based on a formula that assumes the service will be available anywhere within a certain radius of the phone company’s central office. But as our own readers have testified, companies like Qwest, Frontier, and AT&T do not necessarily provide DSL in every central office or within the radius Navigant assumes it should be available. One Stop the Cap! reader in the area has fought Frontier Communications for more than a year to obtain DSL service, and he lives blocks from the local central office. It is simply not available in his neighborhood. AT&T customers have encountered similar problems because the company has deemed parts of its service area unprofitable to provide saturation DSL service. While some multi-dwelling units can obtain 3Mbps DSL, individual homes nearby cannot.

Navigant never visited the impacted communities to inquire whether service was actually available. Instead, it relied on this definition to assume availability:

DSL boundaries were estimated as follows: Based on the location of the dominant central office of each wirecenter, a 12,000 foot radius was generated. This radius was then truncated as necessary to encompass only the servicing wirecenter. The assumption that DSL is capable of serving areas within 12,000 is based on analysis conducted by the Omnibus Broadband Initiative for the National Broadband Plan.

Frontier advertises up to 10Mbps DSL in our neighborhood, but in reality can actually only offer speeds of 3.1Mbps in a suburb less than one mile from the Rochester, N.Y. city line. In more rural areas, customers are lucky to get service at all.

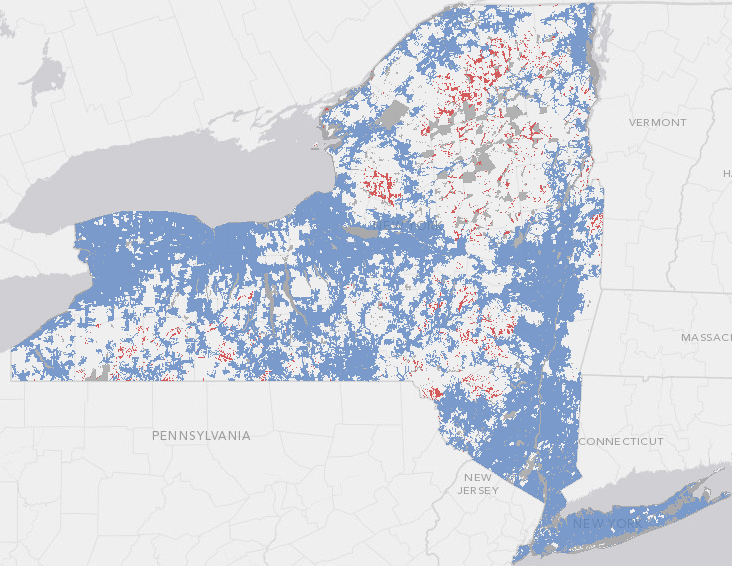

Cable broadband boundaries were estimated based on information obtained from an industry factbook, which gathered provider-supplied general coverage information and extrapolated availability from that. But, as we’ve reported on numerous occasions, provider-supplied coverage data has proven suspect. We’ve found repeated instances when advertised service proved unavailable, especially in rural areas where individual homes do not meet the minimum density required to provide service.

We’ve argued repeatedly for independent broadband mapping that relies on actual on-the-ground data, if only to end the kind of generalizations legislators rely on regarding broadband service. But if the cable industry can argue away the broadband problem with empty claims service is available even in places where it is not (or woefully inadequate), relying on voluntary data serves the industry well, even if it shortchanges rural consumers who are told they have broadband choices that do not actually exist.

Navigant’s report seeks to apply the brakes to broadband improvement programs that can deliver consistent coverage and 21st century broadband speeds that other carriers simply don’t provide or don’t offer throughout the proposed service areas. The cable industry doesn’t welcome the competition, especially in areas stuck with lesser-quality service from low-rated providers.

Subscribe

Subscribe