Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases.

Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases.

Since 2008, Stop the Cap! has witnessed media coverage that breathlessly promises rural broadband is right around the corner, evidenced by a new state or federal grant to build what later turns out to be a middle mile or institutional fiber optic network that is strictly off-limits to homes and businesses. Politicians who participate in these press events tend to favor publicity over performance, often misleading reporters and constituents about just how significant a particular project will be towards resolving a community’s broadband challenges. Much of the time, these projects turn out to serve a very limited number of people or only fund part of a broadband initiative.

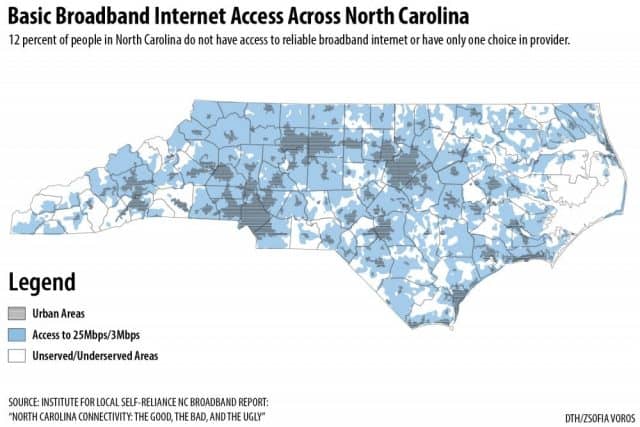

Officials last week said they are hoping to make North Carolina “the first ‘giga-state,’ with broadband access for all its residents.” But to realistically achieve that goal, nothing short of an expenditure of hundreds of millions of dollars will be required to realistically achieve that goal statewide.

A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs.

A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs.

That progress largely stalled after Republicans took control of the state legislature in 2011 and passed a draconian municipal broadband law that effectively banned public broadband expansion. Most of those backing the measure took lucrative campaign contributions from the state’s dominant phone and cable companies. One, Sen. Marilyn Avila, worked so closely with Time Warner Cable’s lobbyists, the resulting bill was effectively drafted by the state’s largest cable company. For that effort, she was later wined and dined by cable lobbyists at a celebration dinner in Asheville.

To be fair, some North Carolina cities are experiencing a broadband renaissance. Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro, Cary, Durham, Winston-Salem, and Chapel Hill will have a choice of providers for gigabit service. Google has installed fiber in some of these cities while AT&T and Charter lay down more fiber optics and introduce upgrades to support gigabit speeds.

Things are considerably worse outside of large cities.

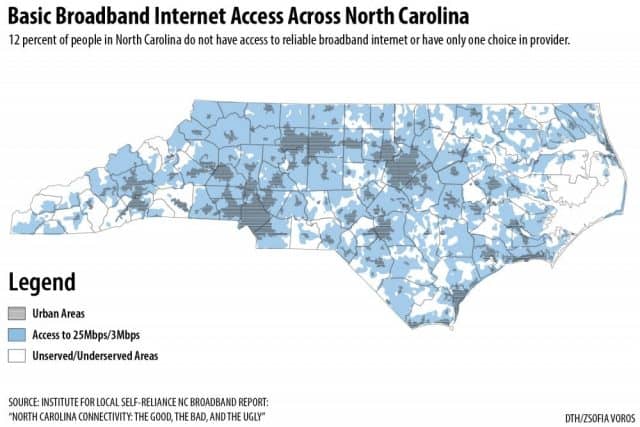

In North Carolina, 585,000 people live in areas where their wired connections cannot reach the FCC’s speed definition of broadband — 25 Mbps, and another 145,000 live without any notion of broadband at all.

In North Carolina, 585,000 people live in areas where their wired connections cannot reach the FCC’s speed definition of broadband — 25 Mbps, and another 145,000 live without any notion of broadband at all.

Bringing all of North Carolina up to at least the nation’s minimum standard for broadband will not be cheap, and politicians and public policy groups must be realistic about the real cost to once and for all resolve North Carolina’s rural broadband challenges. Where the money comes from is a question that will be left to state and local officials and their constituents. Some advocate only tax credit-inspired private funding, others support a public-private partnership to share costs, while still others believe public money should be only spent on publicly owned, locally developed broadband networks. Regardless of which model is proposed, without a specific and realistic budget proposal to move forward, the public will likely be disappointed with the results.

The Facts of Broadband Life

There is a reason rural areas are underserved or unserved. America’s broadband providers are primarily for-profit, investor-owned companies. They are not public servants and they respond first to the interests of their shareholders. Customers might come in second. When a publicly owned utility or co-op is created, in most cases it is the result of years of frustration trying to get a commercial provider to serve a rural or high cost area. Public projects are usually designed to serve almost everyone, even though it will likely take years for construction costs to be recovered. Investor-owned companies are not nearly as patient, and usually demand a Return On Investment formula that offers a much shorter window to recover costs. For broadband, adequately populated areas that can be reached affordably and attract enough new customers to recover the initial investment will get service, while those areas that cannot are left behind. The two populations most likely to fail the ROI test are the urban poor that may not be able to afford to subscribe and rural residents a company claims it cannot afford to serve. Many early cable TV franchise agreements insisted on ROI formulas that allowed companies only to skip areas with inadequate population density, not inadequate income, which explains why cable service is available in even the poorest city neighborhoods, while a wealthy resident in a rural area goes unserved.

Today, most cable and phone companies install fiber optic infrastructure most commonly in new housing developments or previously unwired business parks, while allowing existing copper wire infrastructure already in place elsewhere to remain in service. Some companies, including AT&T and Verizon, have made an effort in some areas to replace copper infrastructure with fiber optics, but in most cases, their rural service areas remain served by copper wiring installed decades ago. As a result, most rural residents end up with DSL internet from the phone company, often at speeds of 5 Mbps or less, or no internet service at all. Neither of these phone companies, much less independent telcos like CenturyLink and Frontier, have shown much interest in scrapping copper wiring for fiber optics in rural service areas. There is simply no economic case that shareholders will accept for costly upgrades that will deliver little, if any, short-term benefits to a company’s bottom line. That reality has led some communities to try incentivizing commercial providers to make an investment anyway, usually with a package of tax breaks and cost sharing. But many communities have achieved better results even faster by launching their own fiber broadband services that the public can access.

Some states with large rural areas have recognized that solving the rural broadband problem will be costly — almost always more costly than first thought. Such projects often take longer than one hoped, and will require some form of taxpayer matching funds, municipal bonds, public buy-in, or a miraculous sudden investment from a generous cable or phone company. In states with municipal broadband bans, like North Carolina, politicians who support such restrictions believe the cable and phone companies will spontaneously solve the rural internet problem on their own. Such beliefs have stalled rural broadband improvements in many of the states ensnared by such laws, usually tailored to protect a duopoly of the same phone and cable companies that have historically refused to offer adequate broadband service to their rural customers.

Challenges for North Carolina

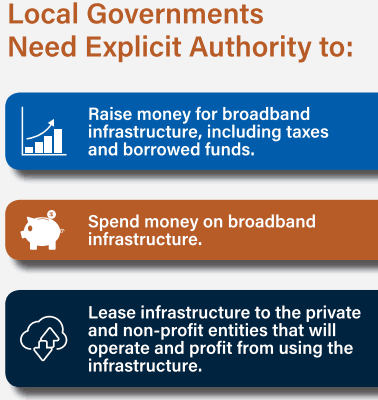

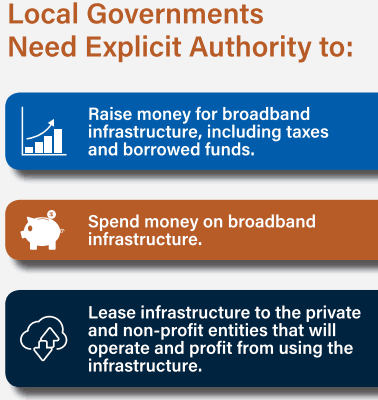

(Courtesy: North Carolina League of Municipalities – Click image for more information)

North Carolina is a growing state, so a small part of the rural broadband problem may work itself out as population densities increase to a level that crosses that critical ROI threshold. But most rural communities will be waiting years for that to happen. Intransigent phone and cable companies are unlikely to respond positively to local officials seeking better service if it requires a substantial investment. As industry lobbyists will tell you, it is not the job of government to dictate the services of privately owned companies. The Republican majority in North Carolina’s legislature underlines that principle regularly in the form of legislation that reduces regulation and oversight. Many, but not all of those Republicans have also taken a strong strand against the idea of municipalities stepping up to resolve their local broadband challenges by working around problematic cable and phone companies. The ideology that government should never be in the business of competing against private businesses usually takes precedence.

Almost a decade ago, the cable and phone companies of North Carolina made three failed attempts to enshrine this principle in a new statewide law that would limit municipal broadband encroachment to such an extent it made future projects unviable. They succeeded in passing a law on their fourth attempt in 2011, the same year Republicans took control in the state legislature.

Today, Republicans still control the legislature with a Democratic governor providing some checks and balances. Why is this important? Because for North Carolina to achieve its goal, it will realistically need a combination of bipartisan support for rural broadband funding and an end to the municipal broadband ban.

Where is the money?

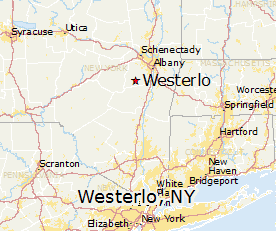

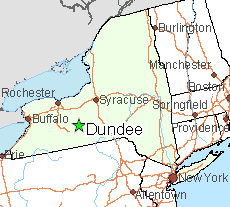

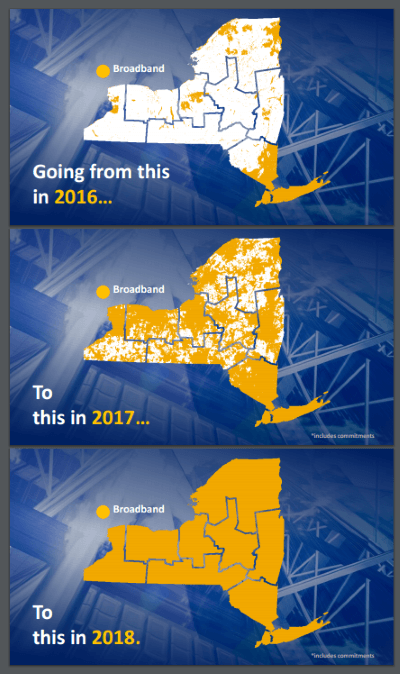

Although North Carolina wants to be America’s first “gigabit” state, New York is the first to at least claim full broadband coverage across the entire state. That did not and could not happen without a multi-year spending program. Recently, North Carolina’s Department of Information Technology launched a $10 million GREAT Grant program to provide last-mile connectivity to the most economically distressed counties in the state. While a noble effort, and one no doubt limited by the availability of funds to spend on broadband expansion, it is a drop in a bucket of water thrown into a barely filled pool.

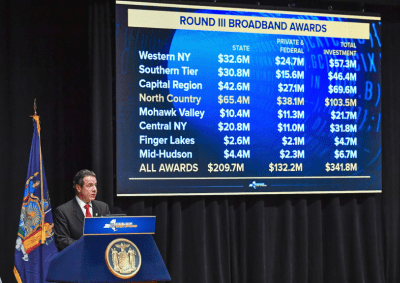

To put this problem in better context, New York’s goal of full broadband coverage (which in our view remains incomplete) required not only $500 million acquired from settlement proceeds won by the state after suing Wall Street banks for causing the Great Recession, but another $170 million in federal broadband expansion funds that were expected to be forfeited because Verizon — the state’s largest phone company — was not interested in the money or upgrading their DSL service upstate.

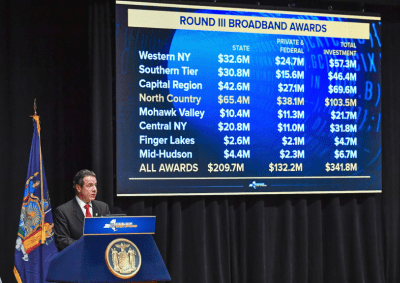

Big Money: New York’s rural broadband funding initiative spent hundreds of millions to attack the rural broadband problem. Gov. Andrew Cuomo outlines funding for just one of several rounds of broadband funding.

Last year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo detailed success for his Broadband for All program by pointing out the state spent $670 million to upgrade or introduce broadband service to 2.42 million locations in rural New York, giving the state 99.9% coverage. That amounts to an average grant of $277 per household or business. In turn, award recipients — largely incumbent phone and cable companies, had to commit to matching private investments. For that state money, the provider had to typically offer at least 100 Mbps service, except in the most rural parts of the state, where a lower speed was acceptable.

North Carolina has 585,000 underserved or unserved locations. Just by using New York’s average $277 grant, North Carolina will have to spend approximately $202 million with similar matching funds from private companies to reach those locations. In fact, it is assuredly more than that because North Carolina’s goal is gigabit speed, not 100 Mbps. Also, New York declared ‘mission accomplished’ while stranding tens of thousands of expensive or difficult to reach residents with subsidized satellite internet access. That offers nothing close to gigabit speed. A more realistic figure for North Carolina in 2019 could be as high as $250-300 million in taxpayer dollars — combined with similar private matching funds to convince AT&T, Charter, CenturyLink and others that the time is right to expand into more rural areas. But as New York discovered, there will be areas in the state no company will bid to serve because the money provided is inadequate.

If the thought of handing over tax dollars to big phone and cable companies bothers you, the alternative is helping communities start and run their own networks in the public interest. Except private providers routinely retaliate with well-funded campaigns of fear, uncertainty and doubt over those projects, and they become political footballs to everyone except their customers, who generally appreciate the service and local accountability.

If North Carolina’s state government relies on a series of $10 million appropriations for grants, it will likely take at least 20 years to wire the state. Stop the Cap! agrees with the goals North Carolina has set to deliver ubiquitous, gigabit-fast broadband. But those goals will be difficult to reach in the present political climate. Republicans in the state legislature approved reductions in the corporate income tax rate to 2.5 percent, down from 3 percent last year, and the personal income tax rate drops to 5.25 percent from 5.499 percent. North Carolina’s latest budget sets aside $13.8 billion for education, $3.8 billion for Medicaid, $3 billion in new debt for road maintenance, and $31 million in grants to attract the film industry to shoot their projects in the state.

It is likely any appropriation significant enough to actually deliver on the commitment to provide total broadband coverage will have to be spread out over several years, unless another funding mechanism can be identified. That assumes the Republicans in the state legislature will be receptive to the idea, which remains an open question.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases.

Solving America’s rural broadband crisis will take a lot more than demonstration projects, token grants, and press releases. A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs.

A decade ago, rural broadband progressed in North Carolina, as communities transitioned away from traditional tobacco and textile businesses to the information and technology economy. To assure a foundation for that economic shift, several communities identified their local substandard (or lacking) broadband as a major problem. The state’s phone and cable companies at the time — notably Time Warner Cable, AT&T, and CenturyLink, often proved to be obstacles by refusing to upgrade networks in the state’s smaller communities. Some cities decided to stop relying on what the broadband companies were willing to offer and chose to construct their own modern, publicly owned broadband network alternatives, open to residents and businesses. A handful of cities in North Carolina went a different direction and acquired a dilapidated and bankrupt cable system and invested in upgrades, hoping cable broadband improvements would help protect their communities’ competitiveness to attract digital economy jobs. In North Carolina,

In North Carolina,

Tens of thousands of rural New York families were hopeful after Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced in 2015 his intention to bring true broadband to every corner of the state by the year 2018. At the time, it was the largest and most ambitious broadband investment of any state in the country, putting $670 million in lawsuit settlement money and rural broadband funds from the FCC on the table to build out rural broadband service other states only talk about.

Tens of thousands of rural New York families were hopeful after Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced in 2015 his intention to bring true broadband to every corner of the state by the year 2018. At the time, it was the largest and most ambitious broadband investment of any state in the country, putting $670 million in lawsuit settlement money and rural broadband funds from the FCC on the table to build out rural broadband service other states only talk about.