Two years after Americans dumped analog television in favor of digital over the air broadcasting, in just over two weeks many Canadians will discover their favorite free-TV signals gone from the analog airwaves forever.

Two years after Americans dumped analog television in favor of digital over the air broadcasting, in just over two weeks many Canadians will discover their favorite free-TV signals gone from the analog airwaves forever.

Canada’s transition to digital TV will take a substantial step forward on Aug. 31st when many Canadian local television stations cease broadcasting in analog. Canada’s pay television providers are taking full advantage of the transition, trying to persuade Canadians who watch their television signals over-the-air for free they will be better off paying for those signals going forward.

Part of the problem is that digital television signals, while “snow-free,” are not pixel-free in many areas distant from the transmitter. As Americans in suburban locations discovered, those trusty indoor rabbit ears may be insufficient to receive an annoyance-free picture.

Digital television signals are not the nirvana some suggest. The same passing vehicles and aircraft that caused wavy analog pictures or other interference can turn a digital picture into a frightfest of frozen picture blocks, digital raining pixels, and other effects that can make watching a difficult signal near impossible.

For Americans who thought the days of the external rooftop antenna were behind them, digital television changed all that, especially in more rural areas that could live with a slightly snowy analog picture, but found sub-optimal digital signals unwatchable.

Canada’s vast expanse, and its accompanying large network of low powered television repeater stations rebroadcasting signals from major stations in provincial capitals and large Canadian cities may prove to be an even greater reception challenge, especially in the Canadian Rockies and hilly terrain in eastern Canada.

Some Canadians experimenting with digital-to-analog converter boxes have found reception less practical than they originally thought.

Peter, a Stop the Cap! reader who lives near Oshawa, Ontario delivers some difficult news:

“Reception of digital signals from Toronto’s CN Tower has proved to be a lot more difficult in Oshawa than the existing analog signals,” Peter writes. “We have no trouble getting truly local signals like CHEX-TV, which has a transmitter in analog serving Oshawa, but watching digital signals from Toronto really requires an outside antenna for good reception.”

Snow may be a thing of the past, but bad digital reception like this may be here to stay for many Canadian viewers.

Peter’s decision to erect a rooftop antenna opened the door to reception of analog and digital signals from Toronto and across Lake Ontario, where he can receive digital signals from some stations in Buffalo and Rochester, N.Y. But it was an expense of several hundred dollars to get the work done.

“Cable and satellite companies are taking full advantage of the digital switch to try and get free-TV viewers to ‘upgrade’ to pay television, and they don’t hesitate to mention the expense and hassle of erecting rooftop antennas to guarantee good digital reception,” Peter says.

Peter can only imagine what digital reception will be like in the Canadian Rockies, where large networks of analog, mostly low-powered UHF transmitters deliver basic reception to important networks, especially CBC, outside of major cities.

“If you visit western Alberta or eastern B.C., good luck to you — we could barely watch over the air signals in most of the mountain towns,” Peter says. “Most people either have cable or satellite already.”

Not every television transmitter is scheduled to switch off analog service at the end of August. Many rural areas are expected to retain analog signals for some time, in part because of the expense of digital conversion and concerns about reception quality. But some areas, particularly near the U.S. border, are scheduled to drop analog signals regardless, potentially causing disruptions for plenty of free-TV viewers. Ottawa is anxious to auction off the vacated frequencies for cell phone, Wi-Fi and wireless broadband use for an estimated $4 billion, and the demand is highest in cities along the U.S. border.

“As many as 1.4 million English-language viewers and 700,000 Francophone viewers may be left without a CBC signal,” Ian Morrison, spokesman for the non-profit Friends of Public Broadcasting, which monitors the CBC and promotes Canadian content on TV and radio told the Toronto Star. “For the most part, these are poorer and older people on fixed incomes who are of no interest to advertisers, but who rely for their news and connection to the community on the CBC, the nearest thing we have in this country to a public broadcaster.”

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission runs a website regarding the transition and includes a list of impacted television stations. Canadian consumers who elect to purchase converter boxes for their analog televisions will pay full price for them — Ottawa has not followed Washington’s lead subsidizing their purchase with a coupon program.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission runs a website regarding the transition and includes a list of impacted television stations. Canadian consumers who elect to purchase converter boxes for their analog televisions will pay full price for them — Ottawa has not followed Washington’s lead subsidizing their purchase with a coupon program.

Meanwhile, many pay television providers are running “digital TV upgrade” specials trying to get Canadians to walk away from free TV in favor of paid video packages:

Shaw Direct: Shaw’s direct to home satellite service has developed the best offer around for qualifying residents in 20 Canadian cities set to lose analog television: free service.

“The Local Television Satellite Solution is [for] households in 20 designated cities that have been receiving their television services over-the-air, and will lose over-the-air access to their local broadcaster because the analog transmitter is being shut down and will not be replaced by a digital transmitter,” a Shaw spokesperson told the Toronto Star. “Shaw will provide a household in a qualifying area with a free satellite receiver and dish that is authorized to receive a package of local and regionally relevant signals from Shaw Direct. There are no monthly programming fees provided that a household qualifies to participate in the program.”

The qualifying cities:

| Barrie |

Fredericton |

Moncton |

Sherbrooke |

| Burmis |

Halifax |

Québec |

St John’s |

| Calgary |

Kitchener |

Saguenay |

Thunder Bay |

| Charlottetown |

Lethbridge |

Saint John |

Trois-Rivières |

| Edmonton |

London |

Saskatoon |

Windsor |

For everyone else, Shaw Direct’s least expensive package is their Bronze – English Essentials tier which runs $41.99 a month.

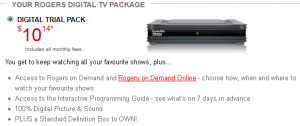

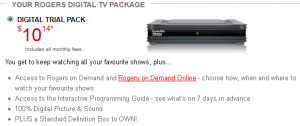

Rogers Cable: Rogers is marketing a special package called Rogers Digital TV which offers up to 85 channels for $10.14 a month, which includes all fees. Many of the channels are included for the first year as a teaser. After that, customers are left with mostly local stations and filler (including — we’re not kidding — the Aquarium Channel, which shows exactly what you think it does. Remember, this is the same cable company that brought you the Swiss Chalet Rotisserie Channel.)

Rogers Cable: Rogers is marketing a special package called Rogers Digital TV which offers up to 85 channels for $10.14 a month, which includes all fees. Many of the channels are included for the first year as a teaser. After that, customers are left with mostly local stations and filler (including — we’re not kidding — the Aquarium Channel, which shows exactly what you think it does. Remember, this is the same cable company that brought you the Swiss Chalet Rotisserie Channel.)

“It’s a fine way to get people used to paying for television, and Rogers introductory price is sure to increase at some point,” suspects Peter. “Maybe you can save a few dollars using those Swiss Chalet meal coupons, though.”

Telus: Western Canada’s largest phone company doesn’t offer much, in comparison. A basic package of Telus IPTV over your phone line — Optik TV — starts at $41 a month for the first six months. Telus Satellite TV starts at $38.27 a month, for the first half of a year. Prices run higher after that. The most Telus will toss in is a $50 credit for a customer referral from a friend or family member.

Look on the bright side: When you pay for Rogers Cable, you can finally get to watch The Rotisserie Channel. The spinning chickens are waiting for you, in digital clarity, 24 hours a day on Ch. 208.

Bell: Another phone company with not a whole lot on offer. Bell’s basic service, which includes TV stations from the U.S. and Canada, starts at $33.50 a month.

Videotron: Quebec’s largest cable company is pitching a combo mini-pack with basic service for $21.29 a month and a required extra channel package starting at $11.17 a month. That’s around $33 a month.

Can you watch online? The CRTC says you may find many of your favorite shows available online for free viewing, but includes the important caveat: most Canadian ISP’s engage in classic Internet Overcharging schemes that include a monthly usage allowance that will curtail substantial online viewing. It should come as little surprise most of the providers in the pay television business in Canada also happen to be the largest Internet Service Providers as well.

About 93 percent of Canadians currently receive television from some form of pay television provider — cable, telco TV, or satellite, according to the CBC. But some of the 7 percent who do not are at risk of losing Canada’s public broadcaster after the conversion. While CBC owns most of the stations and transmitters it broadcasts from, it also affiliates with private stations in certain cities where it does have its own presence.

Come Sept. 1, no over-the-air CBC signals of any kind will be transmitted from London and Kitchener-Waterloo in Ontario; Sherbrooke, Chicoutimi, Quebec City and Trois-Rivières in Quebec; Saint John and Moncton in New Brunswick; Saskatoon, Sask., and Lethbridge, Alta. These are all cities where private stations provided CBC service. Viewers in these areas will need a pay television subscription, or simply go without.

For some of those already subscribing to cable, Sept. 1 also signals the end of some of their favorite stations, as CRTC requires cable providers to prioritize local stations over more distant ones. In southeastern Ontario, for example, a number of viewers will lose access to CBLT, Toronto’s CBC station, and CFTO, Toronto’s CTV affiliate, in favor of “more local” stations in Kingston, Ottawa, and Peterborough.

Subscribe

Subscribe