Greenfield

An important Wall Street analyst has publicly written what many have thought offline for the past six months — the chances of regulators approving a merger of Comcast and Time Warner Cable are growing less and less each day that passes.

Rich Greenfield from BTIG Research has grown increasingly pessimistic about the odds of Comcast winning approval of its effort to buy Time Warner Cable.

Despite the unified view from the executive suites of both cable companies that the merger is a done-deal just waiting for pro forma paperwork to get handled by the FCC and Department of Justice, Greenfield has seen enough evidence to declare “the tide has turned against the cable monopoly in the past 12 months,” and now places the odds of a merger approval at 30 percent or less.

“Since we realized the inevitability of Title II regulation of broadband in December 2014, we have grown increasingly concerned that Comcast and Time Warner Cable will not be allowed to merge,” Greenfield wrote.

The claim from both cable companies that since Comcast and Time Warner Cable do not directly compete with each other, there in no basis on which the government could block the transaction, may become a moot point.

There are three factors that Greenfield believes will likely deliver a death-blow to the deal:

- Monopsony Power

- Broadband Market Share & Control

- Aftershocks from the Net Neutrality Debate

Monopsony power is wielded when one very large buyer of a product or service becomes so important to the seller, it can dictate its own terms and win deals that no other competitor can secure for itself.

Monopsony power is wielded when one very large buyer of a product or service becomes so important to the seller, it can dictate its own terms and win deals that no other competitor can secure for itself.

Comcast is already the nation’s largest cable operator. Time Warner Cable is second largest. One would have to combine most of the rest of the nation’s cable companies to create a force equally important to cable programming networks.

As Stop the Cap! testified last summer before the Public Service Commission in New York, allowing a merger of Comcast and Time Warner Cable would secure the combined cable company volume discounts on cable programming that no other competitor could negotiate for itself. That would deter competition by preventing start-ups from entering the cable television marketplace because they would be at a severe disadvantage with higher wholesale programming expenses that would probably make their retail prices uncompetitive.

Even worse, large national cable programming distributors could dictate terms on what kinds of programming was available.

The FCC recognized the danger of monopsony market power and in the 1990s set a 30% maximum market share limit on the number of video customers one company could control nationally. That number was set slightly above the national market share held by the largest cable company at the time — first known as TCI, then AT&T Broadband, and today Comcast. Comcast sued the FCC claiming the cap was unconstitutional and won twice – first in 2001 when a federal court dismissed the rule as arbitrary and again in 2009 when it threw out the FCC’s revised effort.

The FCC recognized the danger of monopsony market power and in the 1990s set a 30% maximum market share limit on the number of video customers one company could control nationally. That number was set slightly above the national market share held by the largest cable company at the time — first known as TCI, then AT&T Broadband, and today Comcast. Comcast sued the FCC claiming the cap was unconstitutional and won twice – first in 2001 when a federal court dismissed the rule as arbitrary and again in 2009 when it threw out the FCC’s revised effort.

Comcast itself recognized the 30% cap as an important bellwether for regulators watching the concentration of market power through mergers and acquisitions. When it agreed to buy Time Warner Cable, it volunteered to spin-off enough customers of the combined company to stay under the 30% (now voluntary) cap.

Greenfield argues the importance of concentration in the video programming marketplace has been overtaken by concerns about broadband.

“While Comcast tried to steer the government to evaluate the Time Warner deal on the old paradigm of video subscriber share, it is increasingly clear that DOJ and FCC approval/denial will come down to how they view the competitive landscape of broadband and whether greater broadband market share serves the public interest,” Greenfield wrote.

If the Comcast merger deal ultimately fails, the company may have only itself to blame.

If the Comcast merger deal ultimately fails, the company may have only itself to blame.

Last year Comcast faced intense scrutiny over its interconnection agreements with companies that handle traffic for large content producers like Netflix. Comcast customers faced a deterioration in Netflix streaming quality after Comcast refused to upgrade certain connections to keep up with growing demand. Netflix was eventually forced to establish a direct paid connection agreement with the cable operator, despite the fact Netflix offers cable operators free equipment and connections for just that purpose.

That event poured gasoline on the smoldering debate over Net Neutrality and helped fuel support for a strong Open Internet policy that would give the FCC authority to check connection agreements and ban paid online fast lanes.

Seeing how Comcast affected broadband service for millions of subscribers across dozens of states could shift the debate away from any local impacts of the merger and refocus it on how many broadband customers across the country a single company should manage.

Comcast will control 50% or more of the national broadband market when applying the FCC’s newly defined definition of broadband: 25/3Mbps.

That rings antitrust and anticompetitive alarm bells for any regulator.

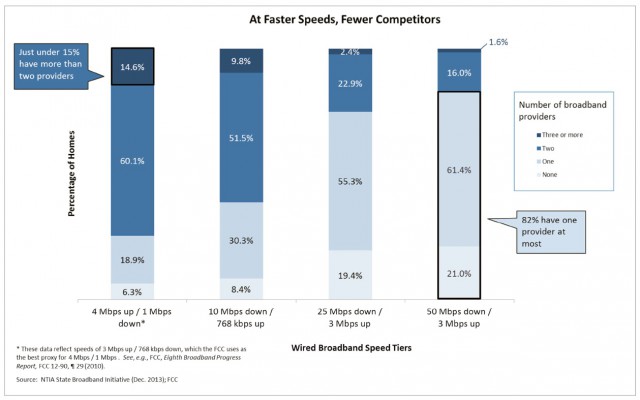

Greenfield notes that changing the definition of broadband will dramatically reshape market share. It will nearly eliminate DSL as a suitable competitor and leave Americans with a choice between cable broadband and Verizon FiOS, community owned fiber networks, Google, and a small part of AT&T’s U-verse footprint. If those competitors don’t exist in your community, you will have no choice at all.

Even Comcast admits cable broadband enjoys a near-monopoly at 25/3Mbps speeds. controlling 89.7% of the market as of December 2013.

Even Comcast admits cable broadband enjoys a near-monopoly at 25/3Mbps speeds. controlling 89.7% of the market as of December 2013.

“If regulators take the ‘national’ approach to evaluating broadband competition, the FCC’s redefinition would appear to put the deal in even greater jeopardy,” Greenfield writes. “Beyond the market share of existing subscribers, the larger issue is availability. Whether or not a current subscriber takes 25/3Mbps or better, the far more relevant question is if a consumer wanted that level of speed do they have a choice beyond their local cable operator? As of year-end 2013, Comcast’s own filing illustrates that in 63% of their footprint post-Time Warner Cable, they were the only consumer choice for 25 Mbps broadband (we suspect even higher now).”

“With Comcast’s scale both before and especially after the Time Warner Cable transaction, they become ‘the only way’ for a majority of Americans to receive content/programming that requires a robust broadband connection,” Greenfield warned.

Even worse, to protect its video business, a super-sized Comcast will be tempted to introduce usage caps that will deliver a built-in advantage to its own services.

“Over time, the fear is that Comcast will favor its own IP-delivered video services versus third parties, similar to how it is able to offer Comcast IP-based video services as a ‘managed’ service that does not count against bandwidth caps, while third-party video services that look similar count against bandwidth caps,” he wrote. “The natural inclination will be for [Comcast] to protect their business (think usage based caps that only apply to outsiders, peering/interconnection fees, etc.)”

“With the overlay of the populist uprising driving government policy, it is hard to imagine how regulators could approve the Comcast Time Warner Cable transaction at this point,” Greenfield concludes. “Comcast continues to try to get the government to look to the past to get its deal approved. But the framework is about not only what is current, but what the future will look like – especially in a rapidly changing broadband world.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Cable One’s history as a former part of the Washington Post and its publishers — the Graham family — will come to an end next year as it is

Cable One’s history as a former part of the Washington Post and its publishers — the Graham family — will come to an end next year as it is

“Those who advocated the Telecommunications Act of 1996 promised more competition and diversity, but the opposite happened,” said Common Cause president Chellie Pingree back in 1995. “Citizens, excluded from the process when the Act was negotiated in Congress, must have a seat at the table as Congress proposes to revisit this law.”

“Those who advocated the Telecommunications Act of 1996 promised more competition and diversity, but the opposite happened,” said Common Cause president Chellie Pingree back in 1995. “Citizens, excluded from the process when the Act was negotiated in Congress, must have a seat at the table as Congress proposes to revisit this law.”

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.”

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.” Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition.

Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition. Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service.

Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service. Although Charter Communications did not succeed in its bid to assume control of Time Warner Cable, it isn’t crying about its loss to Comcast either.

Although Charter Communications did not succeed in its bid to assume control of Time Warner Cable, it isn’t crying about its loss to Comcast either.