Time Warner Cable objects to publicly-owned broadband networks because they represent “unfair” publicly-funded “competition,” despite the fact TWC is also on the public dole.

The next time a cable operator or phone company claims community-owned broadband providers deliver unfair competition because they are government-funded, remind them that quite often that phone or cable company also happens to be on the public dole.

Take Time Warner Cable, which this week won a $5,266,979 grant courtesy of New York State taxpayers to extend their cable system to 4,114 homes in rural parts of upstate New York just outside of the cable company’s current service areas. That equals $1,280.26 in state tax dollars per household. For that public investment, Time Warner will reap private profits for shareholders from selling broadband, cable-TV, phone, and home security services to its newest customers indefinitely.

Now unlike some of my conservative friends, I am not opposed to the state spending money to wire rural New York. It is obvious cable and phone companies will simply never wire these areas on their own so long as Return on Investment conditions fail in these places. What does annoy me are the endless arguments we hear in opposition to public broadband from these same companies, claiming with a straight face that community-owned networks represent “unfair competition” because they are publicly funded. Time Warner Cable is no stranger to public taxpayer benefits itself, having won millions in tax abatements and credits in North Carolina, Ohio and a cool $5 million courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. N.Y. Taxpayer.

Many of the nation’s private telecommunications companies have plenty of love for federal, state, and local officials who have passed favorable tax laws and policies at their behest:

- AT&T not only did not pay any federal taxes in 2011, it actually secured a $420 million taxpayer-subsidized refund;

- Local governments have granted rights-of-way red tape cutting, tax credits and abatements in return for siting important facilities in select areas and hiring an appropriate number of employees to work in them;

- State laws that have made life easy for telecom companies, including statewide video franchising;

- State laws that make life difficult for their would-be competitors, especially public broadband networks.

So let us end the silly rhetoric about public vs. private broadband being a question of fairness. This is really a question about who controls your broadband future, your community or big telecom corporations.

In states like Georgia, elected politicians like Rep. Mark Hamilton want those decisions made by Comcast (Pennsylvania), Windstream (Arkansas) and AT&T (Texas). His bill would make it next to impossible for a local community to do anything but beg and plead the phone company to deliver something, anything that resembles broadband service. For a good part of rural Georgia (and elsewhere), the answer has always been a resounding “no,” at least until the federal government steps up and kicks in your money to help defray the costs of extending Windstream or AT&T’s sub par DSL service that slows to a crawl once the kids are out of school.

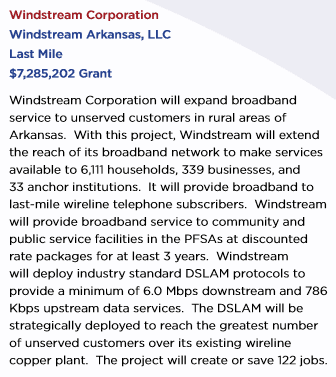

Windstream waited for the federal government to kick in $7.28 million in taxpayer dollars before it would agree to extend its DSL service to rural customers in its own home state of Arkansas.

You have to wonder about the Republicans in Georgia these days who used to fight for local and state control over almost everything. It should be instinctive for any conservative to want out-of-state pointyheads out of their business, but Rep. Mark Hamilton, himself a business owner, seems content forfeiting those rights to companies headquartered hundreds of miles away. If it was the federal government telling Georgia what kind of broadband service it deserves, do you think Mr. Hamilton would be so amenable? Unfortunately, should Hamilton have his way, for the foreseeable future, residents and business owners in Gray, Sparta, or Eatonton to count just a few will have broadband just the way the state’s phone companies want it — super slow DSL, dial-up or satellite fraudband.

Subscribe

Subscribe

“I do not think it is ethical for companies like Windstream, already benefiting from taxpayer dollars, to back a bill that will keep municipalities from offering their residents something better,” said Creekmore.

“I do not think it is ethical for companies like Windstream, already benefiting from taxpayer dollars, to back a bill that will keep municipalities from offering their residents something better,” said Creekmore.

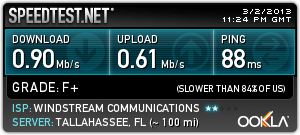

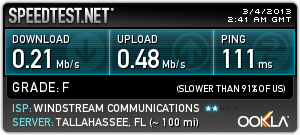

While Windstream continues to heavily lobby the Georgia legislature for a bill that would ban competition from publicly owned broadband providers, the company is doing little to address the growing concerns of its own broadband customers getting poor service.

While Windstream continues to heavily lobby the Georgia legislature for a bill that would ban competition from publicly owned broadband providers, the company is doing little to address the growing concerns of its own broadband customers getting poor service. The horror stories are already clear all over Windstream’s service areas:

The horror stories are already clear all over Windstream’s service areas: A typical day for the Brown family is to wake up, reset the modem, send an e-mail or two, reset the modem, try to go to a web page, reset the modem.

A typical day for the Brown family is to wake up, reset the modem, send an e-mail or two, reset the modem, try to go to a web page, reset the modem. Windstream has announced the increased broadband investments that expanded DSL service to about 75,000 more homes and businesses and brought fiber connections to cell towers are nearly complete and the company intends to dramatically cut spending on further enhancements by the end of 2013.

Windstream has announced the increased broadband investments that expanded DSL service to about 75,000 more homes and businesses and brought fiber connections to cell towers are nearly complete and the company intends to dramatically cut spending on further enhancements by the end of 2013. “We expect to substantially complete our capital investments related to fiber to the tower projects, reaching 4,500 towers by the end of 2013,” said Gardner. “In addition, we will finish most of our broadband stimulus initiatives […] to roughly 75,000 new households. As we exit 2013, we will see capital spending related to these projects decrease substantially.”

“We expect to substantially complete our capital investments related to fiber to the tower projects, reaching 4,500 towers by the end of 2013,” said Gardner. “In addition, we will finish most of our broadband stimulus initiatives […] to roughly 75,000 new households. As we exit 2013, we will see capital spending related to these projects decrease substantially.”

The Georgia Municipal Association notes local governments in small towns and cities, already strapped for resources, would have to prove to the Georgia Public Service Commission that each census block a community wants to serve has no existing broadband service (census blocks are the smallest geographic area the Census Bureau uses for data collection.)

The Georgia Municipal Association notes local governments in small towns and cities, already strapped for resources, would have to prove to the Georgia Public Service Commission that each census block a community wants to serve has no existing broadband service (census blocks are the smallest geographic area the Census Bureau uses for data collection.) The final report of Gov. Nathan Deal’s Competitive Initiative found rural Georgia at a disadvantage simply because many communities cannot get broadband service. Several regions in Georgia called on Deal’s office to help improve inadequate broadband infrastructure.

The final report of Gov. Nathan Deal’s Competitive Initiative found rural Georgia at a disadvantage simply because many communities cannot get broadband service. Several regions in Georgia called on Deal’s office to help improve inadequate broadband infrastructure.