Sprint has begun decommissioning its increasingly obsolete 4G WiMAX network with definitive plans to shut off the service completely by the end of 2015.

Sprint has begun decommissioning its increasingly obsolete 4G WiMAX network with definitive plans to shut off the service completely by the end of 2015.

While most Sprint customers with smartphones have long since moved away from WiMAX, Sprint has resold access to the 2.5GHz network for some prepaid Boost, Sprint, and Virgin Mobile customers as well as third parties including FreedomPop and Earthlink.

WiMAX was the first 4G network in the United States, launching first in Baltimore in the fall of 2008. Sprint customers were offered the HTC Evo 4G smartphone to access WiMAX’s faster speeds. Separately, Clearwire marketed access to WiMAX as a wireless home and business broadband solution. WiMAX was often promoted as a longer distance alternative to Wi-Fi, and was initially capable of 30-40Mbps speeds.

In practice, WiMAX in the United States never achieved great success. Sprint and Clearwire’s network was never built out sufficiently to provide nationwide coverage, and because it relied on very high frequencies, even customers inside claimed service areas often dealt with reception problems, especially indoors. Clearwire’s home broadband replacement often required reception equipment be placed near a window, preferably one without a thermal coating that could block or degrade the signal.

In practice, WiMAX in the United States never achieved great success. Sprint and Clearwire’s network was never built out sufficiently to provide nationwide coverage, and because it relied on very high frequencies, even customers inside claimed service areas often dealt with reception problems, especially indoors. Clearwire’s home broadband replacement often required reception equipment be placed near a window, preferably one without a thermal coating that could block or degrade the signal.

As soon as Sprint and Clearwire added a significant number of customers to the network, speeds deteriorated. Neither company invested enough in upgrades to keep up with demand. Instead, Clearwire’s home broadband customers, originally promised unlimited service, were routinely speed throttled for “excessive use.”

The same year WiMAX was introduced in Baltimore, Network World was already warning the technology was in trouble. By 2011, the magazine had officially declared WiMAX dead.

“There was way too much hype surrounding WiMAX (like the White Spaces today, it was marketed as ‘Wi-Fi on steroids’ and a replacement for Wi-Fi; such was, of course, complete nonsense)”, the magazine wrote.

Other American wireless carriers showed little interest in WiMAX, particularly as competing 4G technologies including HSPA+ and LTE were nearing deployment.

Despite the promise of greatly enhanced data speeds with the next generation of WiMAX, dubbed WiMAX 2, many of the world’s largest wireless carriers were already preparing to move on. In particular, China Mobile (and its 600 million customers) became the decisive factor that turned WiMAX 2 into a bad bet. China Mobile decided the better choice was TD-LTE, a variant of LTE technology. With China Mobile providing service to 10 percent of the world’s mobile users all by itself, support for TD-LTE grew and attracted equipment manufacturers that saw the earnings potential from selling tens of millions of base stations.

Despite the promise of greatly enhanced data speeds with the next generation of WiMAX, dubbed WiMAX 2, many of the world’s largest wireless carriers were already preparing to move on. In particular, China Mobile (and its 600 million customers) became the decisive factor that turned WiMAX 2 into a bad bet. China Mobile decided the better choice was TD-LTE, a variant of LTE technology. With China Mobile providing service to 10 percent of the world’s mobile users all by itself, support for TD-LTE grew and attracted equipment manufacturers that saw the earnings potential from selling tens of millions of base stations.

TD-LTE is an excellent upgrade choice for WiMAX operators because it was designed to work best at high frequencies ranging from 1850-3800MHz — the same frequency bands that WiMAX already uses.

Sprint expects to decommission at least 6,000 of its 17,000 WiMAX cell sites. Another 5,000 of those sites have already gotten TD-LTE technology, a part of Sprint’s broader LTE network upgrade. Sprint will combine its FDD-LTE network in its 800MHz and 1.9GHz spectrum with a TD-LTE network in its 2.5GHz spectrum. Sprint Spark customers are being offered tri-band equipment that can access either technology. Sprint can use its massive expanse of 2.5GHz spectrum to offload data usage from its lower frequency spectrum, especially in large cities.

Another 5,000 legacy Clearwire cell sites will be upgraded to TD-LTE between now and the end of next year. Sprint expects to deploy TD-LTE more widely than WiMAX, potentially serving 100 cities and 100 million base stations by 2016.

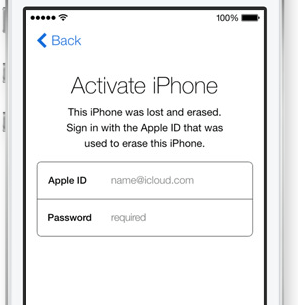

Sprint has protected much of its postpaid customer base from the transition by repeatedly encouraging customers to upgrade to LTE service, now being rolled out as part of its Network Vision plan. But firms like FreedomPop and others that now lease access to the WiMAX network will leave their customers with a shorter upgrade path when WiMAX equipment stops working, requiring users to upgrade to LTE equipment.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Sprint Spark – Today is already the future 10-30-13.mp4[/flv]

Sprint hypes its new tri-band Sprint Spark network, which combines two different LTE networks to deliver faster data speeds. (1:18)

Subscribe

Subscribe

Since 2002, New York Tax Law has required mobile phone companies to collect and pay sales taxes on the full amount of the monthly access charges for their calling plans. For example, when a customer pays Sprint a fixed monthly charge of $39.99 for 450 minutes of mobile calling time, the law requires Sprint to collect and pay sales taxes on the entire $39.99. According to the Attorney General’s complaint, starting in 2005, Sprint illegally failed to collect and pay New York sales taxes on an arbitrarily set portion of its revenue from these fixed monthly access charges.

Since 2002, New York Tax Law has required mobile phone companies to collect and pay sales taxes on the full amount of the monthly access charges for their calling plans. For example, when a customer pays Sprint a fixed monthly charge of $39.99 for 450 minutes of mobile calling time, the law requires Sprint to collect and pay sales taxes on the entire $39.99. According to the Attorney General’s complaint, starting in 2005, Sprint illegally failed to collect and pay New York sales taxes on an arbitrarily set portion of its revenue from these fixed monthly access charges.

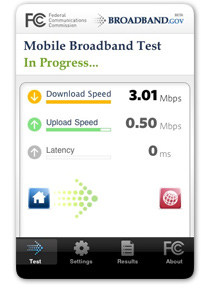

Are you getting the mobile broadband speeds your provider advertises for its whiz-bang 4G network? How do you know which carrier really delivers?

Are you getting the mobile broadband speeds your provider advertises for its whiz-bang 4G network? How do you know which carrier really delivers? Millenicom customers have had their ups and downs over the last two weeks coping with e-mail notifications they would lose, keep, and once again lose their unlimited wireless data plan.

Millenicom customers have had their ups and downs over the last two weeks coping with e-mail notifications they would lose, keep, and once again lose their unlimited wireless data plan. Blue Mountain Internet (BMI) offers an “unlimited plan” that isn’t along with several usage allowance plans. BMI strongly recommends the use of their Mobile Broadband Optimizer software that compresses web traffic, dramatically improving speeds and reducing consumption:

Blue Mountain Internet (BMI) offers an “unlimited plan” that isn’t along with several usage allowance plans. BMI strongly recommends the use of their Mobile Broadband Optimizer software that compresses web traffic, dramatically improving speeds and reducing consumption: There is a $100 maximum on overlimit fees, but BMI reserves the right to suspend accounts after running 3-5GB over a plan’s allowance to limit exposure to the penalty rate. The compression software is for Windows only and does not work with MIFI devices or with video/audio streaming. BMI warns its wireless service is not intended for video streaming. Customers are not allowed to host computer applications including continuous streaming video and webcam posts that broadcast more than 24 hours; automatic data feeds; automated continuous streaming machine-to-machine connections; or peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing.

There is a $100 maximum on overlimit fees, but BMI reserves the right to suspend accounts after running 3-5GB over a plan’s allowance to limit exposure to the penalty rate. The compression software is for Windows only and does not work with MIFI devices or with video/audio streaming. BMI warns its wireless service is not intended for video streaming. Customers are not allowed to host computer applications including continuous streaming video and webcam posts that broadcast more than 24 hours; automatic data feeds; automated continuous streaming machine-to-machine connections; or peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing.

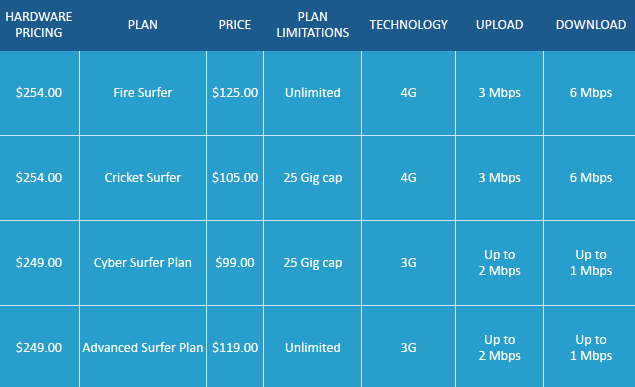

Wireless ‘n Wifi

Wireless ‘n Wifi