Several years after wireless unlimited data plans became grandfathered or riddled by speed throttling, America’s third and fourth largest carriers have decided the marketplace wants “unlimited everything” after all and is prepared to give customers what they want, at least until they read the fine print.

Several years after wireless unlimited data plans became grandfathered or riddled by speed throttling, America’s third and fourth largest carriers have decided the marketplace wants “unlimited everything” after all and is prepared to give customers what they want, at least until they read the fine print.

T-Mobile Announces “The Era of the Data Plan is Over”: T-Mobile ONE

T-Mobile CEO John Legere used a video blog to announce a major shakeup of T-Mobile’s wireless plans this morning, centered on the concept of “unlimited everything.”

“The era of the data plan is over,” said Legere. T-Mobile’s new plan — T-Mobile ONE — does away with usage caps and usage-based billing and offers unlimited calls, texting, and data on the company’s 4G LTE network. The plan becomes available Sept. 6 at T-Mobile stores nationwide and t-mobile.com for postpaid customers. Prepaid plans will be available later.

“Only T-Mobile’s network can handle something as huge as destroying data limits,” said Legere. “Dumb and Dumber can’t do this. They’ve been running away from unlimited data for years now, because they built their networks for phone calls, not for how people use smartphones today. I hope AT&T and Verizon try to follow us. In fact, I challenge them to try.”

Legere

T-Mobile claims the savings with its unlimited plan are enormous compared to its bigger competitors AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

Verizon’s largest LTE usage-capped data plan would cost a family of four $530/month. That’s $4,440 more than T-Mobile ONE will charge.

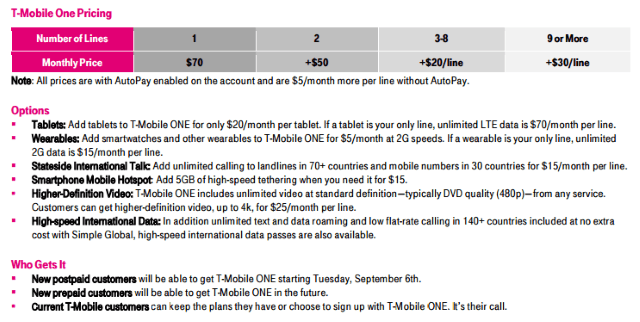

T-Mobile ONE costs $70 a month for the first line, $50 a month for the second, and additional lines are $20 a month, up to 8 lines with auto pay (add $5 per line if you don’t want autopay). Customers can add tablets for an extra $20 a month.

T-Mobile does offer some caveats in the fine print which are relevant to customers:

- All video streaming on this plan is throttled to support a maximum of 480p picture quality. Higher video quality is available with an HD add-on plan for $25/mo per line;

- Tethering is included with T-Mobile ONE, but it is painfully speed-limited to 2G speeds — around 70kbps, just a tad faster than dial-up. At that speed, a web page that will take less than five seconds to load on a 4G network will take 17-25 seconds. A 60 second YouTube video will take nearly five minutes to watch, and downloading apps or sharing images is often impossible because of timeouts. If you want 4G tethering, that will be $15 a month for 5GB, please;

- Customers identified as among the top 3% of data users, typically those who use more than 26GB of 4G LTE data a month will find themselves in the same data doghouse T-Mobile’s Simple Choice customers are in. That means during peak usage periods on busy cell towers, heavier users are deprioritized on T-Mobile’s network, but we’re not sure if that results in slight speed reductions or the kind of drastic 2G-like experience these kinds of “fair usage” policies often deliver.

Our analysis:

While we’re happy to see unlimited data plans return to prominence, T-Mobile is continuing to punish high bandwidth applications, tethering, and usage outliers with frustrating speed throttles.

While we’re happy to see unlimited data plans return to prominence, T-Mobile is continuing to punish high bandwidth applications, tethering, and usage outliers with frustrating speed throttles.

T-Mobile’s biggest source of increasing traffic is coming from online video. About a year ago, Legere introduced T-Mobile’s Binge On program, which offers streaming video from T-Mobile’s partners without it counting against your usage allowance. This program had the potential of causing problems with the Federal Communications Commission’s Net Neutrality rules.

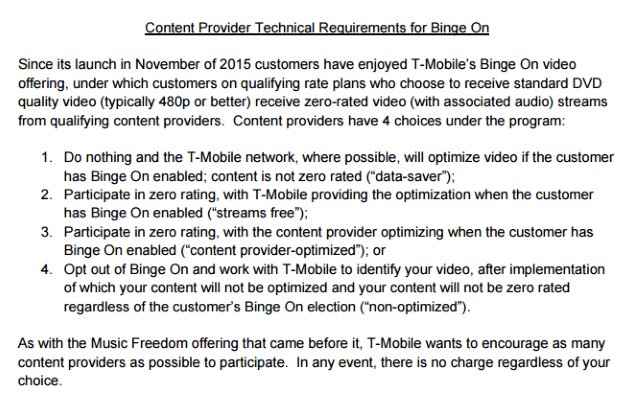

Legere seemed to avoid trouble by revealing enough information about Binge On to make it clear why the program exists — to reduce video traffic’s impact on T-Mobile’s network. That might seem counterintuitive until one looks at what it takes to be a Binge On partner — allowing T-Mobile’s Binge On-related traffic to be “optimized” to Standard Definition video (around 480p). No money changes hands between T-Mobile and its Binge On partners.

T-Mobile makes it easy to be a Binge On participant.

Binge On was an important factor in freeing up bandwidth on T-Mobile’s network. Some analysts suggest two-thirds of T-Mobile’s video traffic load disappeared after Binge On was introduced. Video is likely the single biggest bandwidth consuming application on wireless networks today. If a customer is watching on a smartphone or even a small tablet, 480p video is generally adequate and has a lower chance of stopping to buffer.

Another clue about the impact of online video on T-Mobile’s network is the same video throttling strategy is built into T-Mobile ONE and applies to all online video, whether the provider partners with T-Mobile or not. Also consider the extraordinary cost of the optional HD Video add-on, which defeats video throttling: a whopping $25 per month per device. That kind of pricing clearly suggests 1080p or even 4K video is a major resource hog for T-Mobile, and customers looking for this level of video quality are going to pay substantially to get it.

Another clue about the impact of online video on T-Mobile’s network is the same video throttling strategy is built into T-Mobile ONE and applies to all online video, whether the provider partners with T-Mobile or not. Also consider the extraordinary cost of the optional HD Video add-on, which defeats video throttling: a whopping $25 per month per device. That kind of pricing clearly suggests 1080p or even 4K video is a major resource hog for T-Mobile, and customers looking for this level of video quality are going to pay substantially to get it.

T-Mobile is also clearly concerned about tethering, relegating hotspot and tethered device traffic to 2G speeds, which will quickly deter anyone from depending on it except in emergencies. Again, traffic is the issue. Some semi-rural customers unserved by cable but able to get a 4G signal from a T-Mobile tower may think of using T-Mobile as their exclusive source of internet access. At speeds just above dial-up, they won’t consider this an option.

We’re also disappointed to see 26GB of usage a month as the threshold for potential speed throttling. T-Mobile ONE is not cheap, and without more detailed information about how often those exceeding 26GB face speed slowdowns, how much of a slowdown, and how quickly those speed reductions disappear when the tower gets less congested would be very useful. Until then, customers are likely to interpret 26GB as a type of soft usage allowance they will not want to exceed.

T-Mobile ONE also delivers a powerful signal to Wall Street because it raises the lowest price a T-Mobile postpaid customer can pay to become a customer from $50 to $70 a month for a single line. That’s quite a burden for some customers who will have to look to prepaid plans or resellers to get cheaper service. Other carriers rushed to meet T-Mobile’s $50 2GB plan when it was introduced, which has served as an entry-level price range for occasional data dabblers. If those carriers don’t immediately raise prices as well, they will undercut T-Mobile. That could provoke an increase in cancellations among customers buying on price, not plan features. T-Mobile is banking consumers will appreciate unlimited data enough to pay extra for peace of mind.

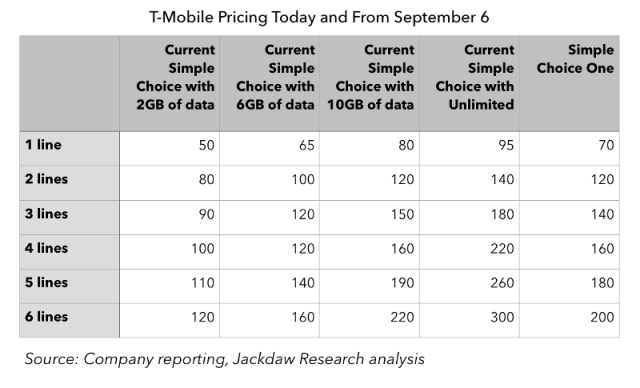

Jackdaw Research found customers enrolled in 2GB and 6GB T-Mobile plans will see a price increase with T-Mobile ONE. Those signed up for 10GB or unlimited service will pay the same or slightly less.

Sprint: Unlimited Freedom: Two Lines of Unlimited Talk, Text, and Data for $100/month

Sprint: Unlimited Freedom: Two Lines of Unlimited Talk, Text, and Data for $100/month

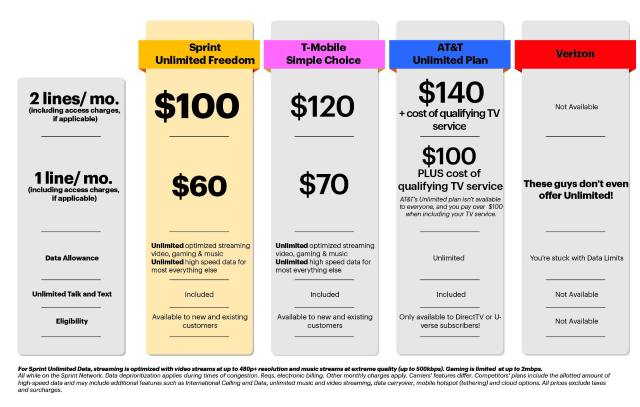

Not to be outdone by T-Mobile, Sprint CEO Marcelo Claure today announced his own company’s overhaul of wireless plans, featuring the all-new Sprint Unlimited Freedom plan, which offers two lines of unlimited talk, text and data for $100 a month, with no access charges or hidden fees.

Starting Friday, Aug. 19, Sprint customers can sign up for the new plan, which costs $60 for the first line, $100 for two lines, and $30 for each additional line, up to 10. Sprint pounced on the fact its Unlimited Freedom plan for two is $20 less than T-Mobile charges.

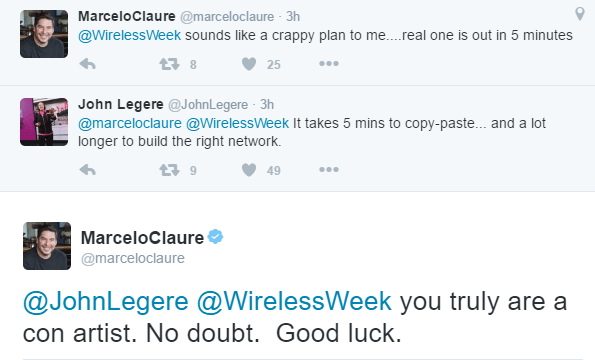

Otherwise the two plans are remarkably similar — too similar for the CEOs of both companies that spent part of today engaged in a Twitter war.

T-Mobile CEO John Legere and Sprint CEO Marcelo Claure traded tweet barbs this morning.

“Sprint’s new Unlimited Freedom beats T-Mobile and AT&T’s unlimited offer – only available to its DirecTV subscribers – while Verizon doesn’t even offer its customers an unlimited plan,” read Sprint’s press release.

“Wireless customers want simple, worry-free and affordable wireless plans on a reliable network,” said Marcelo Claure, Sprint president and CEO. “There can be a lot of frustration and confusion around wireless offers, with too much focus on gigabytes and extra charges. Our answer is the simplicity of Unlimited Freedom. Now customers can watch their favorite movies and videos and stream an unlimited playlist at an amazing price.”

“Wireless customers want simple, worry-free and affordable wireless plans on a reliable network,” said Marcelo Claure, Sprint president and CEO. “There can be a lot of frustration and confusion around wireless offers, with too much focus on gigabytes and extra charges. Our answer is the simplicity of Unlimited Freedom. Now customers can watch their favorite movies and videos and stream an unlimited playlist at an amazing price.”

Sprint has also essentially joined the T-Mobile optimization bandwagon, limiting streaming video to 480p, but it goes further with optimization of games — limited to 2Mbps, and music — limited to 500kbps. There does not seem to be any option to pay more to avoid the “optimization” and Sprint is not offering a tethering option with this plan.

“While we initially questioned using mobile optimization for video, gaming and music, the decision was simpler when consumers said it ‘practically indistinguishable’ in our tests with actual consumers,” said Claure. “In fact, most individuals we showed could not see any difference between optimized and premium-resolution streaming videos when viewing on mobile phone screens. Both provide the mobile customer clear, vibrant videos and high-quality audio. Mobile optimization allows us to provide a great customer experience in a highly affordable unlimited package while increasing network efficiency.”

Also, beginning Friday, Aug. 19, Sprint’s leading prepaid brand, Boost Mobile introduces its own unlimited offer, Unlimited Unhook’d:

Also, beginning Friday, Aug. 19, Sprint’s leading prepaid brand, Boost Mobile introduces its own unlimited offer, Unlimited Unhook’d:

- Unlimited talk, text and optimized streaming videos, gaming and music

- Unlimited nationwide 4G LTE data for most everything else

- $50 a month for one line

- $30 a month for a second line up to five total lines

In addition to the Unlimited Unhook’d plan, Boost Mobile will also unveil the $30 Unlimited Starter plan, which includes unlimited talk, text and slower network data (2G or 3G) with 1GB of 4G LTE data. Customers looking for more high-speed data can add 1 GB of 4G LTE data for $5 per month or 2 GB of 4G LTE data for $10 per month. Multi-line plans are also available for families looking to save some money for an additional $30 a month per line.

“There’s a lot of confusion and clutter in prepaid, but is doesn’t have to be that way. Boost Mobile is offering the simplest solution with plans that are easy to understand,” said Claure. “Boost has something for everyone, whether you need a truly unlimited plan with 4G LTE data or want to save extra money with a low-cost plan.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Some of America’s largest telecommunications companies continue to pay almost nothing in federal taxes even as state taxing authorities hungry for revenue are getting more aggressive about denying access to tax loopholes and suing some for failing to pay their fair share.

Some of America’s largest telecommunications companies continue to pay almost nothing in federal taxes even as state taxing authorities hungry for revenue are getting more aggressive about denying access to tax loopholes and suing some for failing to pay their fair share. Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court turned away

Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court turned away  While $300 million sounds like a lot, it pales in comparison to the money Verizon manages to dodge paying the Internal Revenue Service. The phone company is the poster child of corporate tax dodging according to Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Sanders targeted Verizon because between 2008-2013, Verizon not only did not pay a nickel in federal taxes, it actually received a refund from the federal government after achieving a federal tax rate of -2.5%, despite booking $42.5 billion in profits. American taxpayers effectively subsidized Verizon when it got its refund check.

While $300 million sounds like a lot, it pales in comparison to the money Verizon manages to dodge paying the Internal Revenue Service. The phone company is the poster child of corporate tax dodging according to Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Sanders targeted Verizon because between 2008-2013, Verizon not only did not pay a nickel in federal taxes, it actually received a refund from the federal government after achieving a federal tax rate of -2.5%, despite booking $42.5 billion in profits. American taxpayers effectively subsidized Verizon when it got its refund check. Bruce Kushnick, executive director of the New Networks Institute, claims

Bruce Kushnick, executive director of the New Networks Institute, claims

Sprint customers will once again have to endure service interruptions and disruptions and the possibility of degraded service after the cellular company quietly announced it was terminating leases with Crown Castle and American Tower — two of the largest owners of shared communications towers in the country, and relocating Sprint cell sites to government-owned property.

Sprint customers will once again have to endure service interruptions and disruptions and the possibility of degraded service after the cellular company quietly announced it was terminating leases with Crown Castle and American Tower — two of the largest owners of shared communications towers in the country, and relocating Sprint cell sites to government-owned property. The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time,

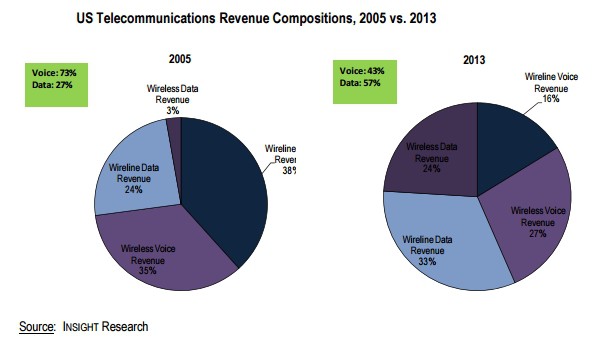

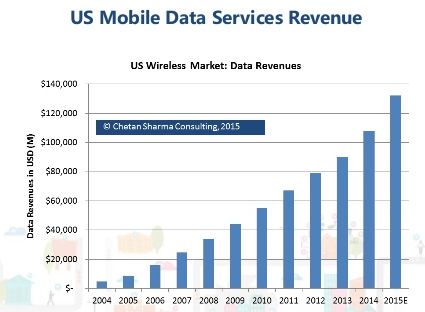

The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time,  Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging.

Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging. The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier.

The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier. Some even expect carriers to eventually

Some even expect carriers to eventually  Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint

Sprint customers thinking about subscribing to an unlimited data plan may want to decide before Oct. 16, when Sprint