Netflix continues to step up its attacks on providers who implement Internet Overcharging schemes on their wired broadband customers.

Netflix continues to step up its attacks on providers who implement Internet Overcharging schemes on their wired broadband customers.

That concern is understandable as Netflix increasingly transitions to broadband streaming instead of mailing DVD’s to customers.

Getting in the way are five of the nation’s seven largest broadband providers, all imposing limits on customers just as they discover they might be able to do without cable television.

Netflix’s streamed HD shows now consume around 2GB per hour, according to Netflix general counsel David Hyman. That can eat through usage allowances quickly. Hyman penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal last year blasting the practices of usage caps and consumption billing.

“Wireline bandwidth is an almost unlimited resource due to advances in Internet architecture,” Hyman wrote. “The marginal cost of providing an extra gigabyte of data—enough to deliver one episode of 30 Rock from Netflix—is less than one cent, and falling.”

That doesn’t seem to matter much to Comcast, CenturyLink, Charter Communications, and Cox. All four providers have introduced hard usage limits on customers — a usage cap. Exceeding it gives any of those providers the right to cut off your broadband service. AT&T, always one to see a financial angle, charges for excess use of their DSL and U-verse service — $10 for every 50GB. Time Warner Cable recently announced its own experimental “optional” usage pricing package for very light users who consume fewer than 5GB per month. It will slap overlimit fees on those participating customers who break through the 5GB ceiling at a rate of $1/GB, an enormous markup.

Providers with strict caps usually argue they come as a result of their own network’s capacity problems. Cable operators who do not consistently manage their network traffic can experience traffic clogs by overselling service without upgrading capacity to sustain user demand. But providers like Comcast, Cox, and Charter resolved those capacity problems with upgrades to DOCSIS 3 technology, which offer operators an exponentially bigger pipeline for Internet traffic.

Although Comcast promised to regularly review and adjust usage caps since implementing them four years ago, the nation’s largest cable operator has thus far seen no need to raise them.

“We feel that that is an extraordinarily large amount of data,” says Comcast’s Charlie Davis. “That limit is there to make sure we provide a great online experience for every single paying customer.”

Wall Street bankers have closely monitored the industry’s early results from Internet Overcharging, and have been encouraged, so long as operators implement it carefully.

Credit Suisse in a 2011 report to its investor clients suggested the key for successful usage-based pricing is to introduce it slowly and keep “sticker shock to a minimum in the early days” to reduce backlash by consumers and lawmakers.

Once established, the sky is the limit.

Once established, the sky is the limit.

Netflix itself is also battling an Internet Overcharging scheme it faces — double-dipping by cable operators like Comcast. In addition to the fees Comcast collects from customers for its broadband service, the cable operator also wants to be paid directly by Netflix to allow the movie service’s traffic on its network.

That’s an Internet toll booth, charges Netflix and consumer groups. It’s also uncompetitive, says Hyman.

This month Comcast unveiled its own movie and TV show streaming service — Xfinity Streampix — from which, unsurprisingly, the cable company has not sought extra traffic payments from itself.

Three providers which don’t cap customers don’t see a reason to try.

Verizon Communications says its fiber network FiOS has plenty of capacity and has no plans to restrict customers’ enjoyment of the service. In 2009, Cablevision’s Jim Blackley told one panel discussion usage caps are not in the cards.

“We don’t want customers to think about byte caps so that’s not on our horizon,” Blackley said. “We literally don’t want consumers to think about how they’re consuming high-speed services. It’s a pretty powerful drug and we want people to use more and more of it.”

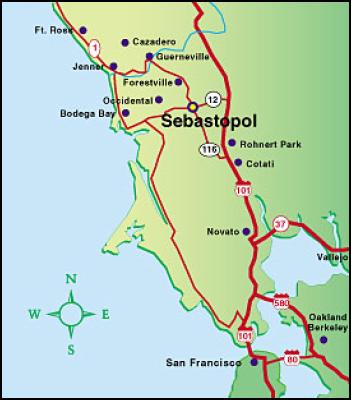

California’s Sonic.net Inc., goes even further. Its CEO, Dane Jasper, believes the Federal Communications Commission needs to be more assertive about protecting America’s broadband revolution and the customers that depend on the service.

The fact different operators can take radically different positions on the subject, despite running similar networks, suggests technical necessity is not the reason providers are implementing usage restrictions and extra fees on customers.

As Hyman writes:

Bandwidth caps with fees piled on top are a lousy way to manage traffic. All of the costs of supplying residential broadband are for supporting peak usage. Bandwidth consumed off-peak is completely free. If Internet service providers really wanted to manage traffic efficiently, they would limit speeds at peak times. If their goal is instead to increase revenues or lessen competition, getting consumers to pay per gigabyte is an excellent strategy.

Consumer access to unlimited bandwidth is good for society. It fosters innovation, drives commerce, and advances political and social discourse. Given that bandwidth is cheap and plentiful and will only grow more so with time, there is no good reason for bandwidth caps and fees to take root.

Consumers and regulators need to take heed of what is happening and avoid winding up like the proverbial frog in a pot of boiling water. It’s time to jump before it’s too late.

Subscribe

Subscribe