Last week, AT&T announced its intention to abandon an appeal of a decision of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals granting the Federal Trade Commission the right to continue its lawsuit against AT&T for speed throttling its “unlimited data” wireless customers.

Last week, AT&T announced its intention to abandon an appeal of a decision of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals granting the Federal Trade Commission the right to continue its lawsuit against AT&T for speed throttling its “unlimited data” wireless customers.

The notification came in a surprising four sentence notice filed with the court May 30:

At the May 10, 2018 case management conference in this matter, AT&T informed the Court that it expected at that time to request a 60-day extension from the Supreme Court of the deadline to file a petition for certiorari. See Audio Recording of May 10, 2018 Hr’g at 7:22. Since that hearing, AT&T has decided not to request such an extension and not to file a petition for certiorari to review the decision of the en banc Ninth Circuit, see 883 F.3d 848 (9th Cir. 2018). The deadline to file a petition for certiorari lapsed on May 29, 2018.

AT&T spokesman Mike Balmoris later told reporters: “We have decided not to seek review by the Supreme Court, to focus instead on negotiating a fair resolution of the case with the Federal Trade Commission.”

AT&T’s sudden change of heart surprised many observers, including some closely following the case at the 9th Circuit, which has held regular court supervised meetings to prepare for the widely expected Supreme Court challenge. AT&T notified the court in early May it would file its appeal as soon as May 29, and the court was preparing new discovery guidelines and deadlines between the two parties as the case proceeded.

AT&T had achieved a major victory in 2017 when a three-judge panel at the Ninth Circuit agreed with AT&T’s argument that the FTC had no jurisdiction over the company because part of its business includes traditional telephone service, something defined in law as being regulated exclusively by the FCC. At the same time, the FCC did not seem to have jurisdiction either, because wireless data throttling took place over a network not subject to common carrier service regulations.

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals — San Francisco.

The Ninth Circuit then agreed to hear the case once again, this time “en banc” — meaning the full court would re-hear the case instead of a limited panel of three judges. In February, the court unanimously found the FTC did have regulatory jurisdiction over AT&T after all:

We conclude that the exemption in Section 5 of the FTC Act – “except . . . common carriers subject to the Acts to regulate commerce” – bars the FTC from regulating “common carriers” only to the extent that they engage in common-carriage activity. By extension, this interpretation means that the FTC may regulate common carriers’ non-common-carriage activities.

[…] This statutory interpretation also accords with common sense. The FTC is the leading federal consumer protection agency and, for many decades, has been the chief federal agency on privacy policy and enforcement. Permitting the FTC to oversee unfair and deceptive non-common-carriage practices of telecommunications companies has practical ramifications. New technologies have spawned new regulatory challenges. A phone company is no longer just a phone company. The transformation of information services and the ubiquity of digital technology mean that telecommunications operators have expanded into website operation, video distribution, news and entertainment production, interactive entertainment services and devices, home security and more. Reaffirming FTC jurisdiction over activities that fall outside of common-carrier services avoids regulatory gaps and provides consistency and predictability in regulatory enforcement.

In short, AT&T’s “get out of regulatory oversight free”-card was revoked, much to its consternation. The company promised a fast appeal to the Supreme Court. The case concerned a number of observers, not the least of which was the Federal Communications Commission, which has been so concerned about AT&T’s novel argument to escape regulation, it filed a brief supporting the FTC with the court:

If the en banc Court were to adopt AT&T’s position that the FTC Act’s common-carrier exception is “status-based” rather than “activity-based,” contrary to the reasoned analysis of the district court below, the fact that AT&T provides traditional common-carrier voice telephone service could potentially immunize the company from any FTC oversight of its noncommon-carrier offerings, even when the FCC lacks authority over those offerings—creating a potentially substantial regulatory gap where neither the FTC nor the FCC has regulatory authority.

That approach is contrary to a common-sense reading of the relevant statutes and could weaken or eliminate important consumer protections. While AT&T may prefer to offer services in a regulatory no man’s land, the law does not dance to AT&T’s whims.

While AT&T publicly expressed confidence about its appeal right up to the day it abandoned it, minutes from the Ninth Circuit trial scheduling and progress conferences reveal AT&T and the FTC were already privately talking with each other to avoid further litigation:

While AT&T publicly expressed confidence about its appeal right up to the day it abandoned it, minutes from the Ninth Circuit trial scheduling and progress conferences reveal AT&T and the FTC were already privately talking with each other to avoid further litigation:

“Parties reported that they are conducting settlement negotiations.”

All observers agree a successful appeal by AT&T to the Supreme Court could have put telecommunications laws and regulations into chaos. Had AT&T successfully restored the three-judge panel’s decision, any telecommunications company could walk away with impunity from FCC and FTC oversight by simply starting a small telephone company serving just a handful of customers. Just one product or service subject to common carrier rules could effectively immunize a phone or cable company from regulations indefinitely, or until Congress changed the law to close that loophole.

Some observers predict AT&T’s decision not to appeal is a prelude to an imminent, favorable permanent settlement of the four-year old case. The evidence strongly suggests AT&T will likely escape any significant monetary punishment, and affected consumers may not get significant (if any) compensation for AT&T’s prior acts:

- The FCC shows no sign of following through on a 2015 press release threatening AT&T with $100 million in fines for its failure to properly disclose its speed throttling policy arbitrarily imposed on unlimited data customers who exceeded a company-defined amount of data usage. At the time the press release was issued, there were three Democrats and two Republicans serving on the Commission. Both of those Republicans opposed the fine and are now part of the Republican majority at the FCC under the Trump Administration. The FCC admitted in court papers that no further action has been taken to fine AT&T. The case was largely left in the hands of the FTC.

- During the Obama Administration, the FTC claimed it was interested in pursuing refunds for affected customers and punishing AT&T for its throttling practices. Last week, Andrew Smith, the FTC’s new director of the Consumer Protection Bureau told an audience today’s priority it to monitor providers over traffic throttling and making sure those practices are transparently disclosed to customers. “We’re planning to examine current practices in the industry,” Smith said. “We’re looking for areas in which ISPs may be engaged in unfair or deceptive practices, and we will bring enforcement action as appropriate.”

Smith

For AT&T, the decision to drop its appeal may have come down to whether it preferred to temporarily escape regulatory oversight until an enraged Congress passed new laws to put AT&T and other telecom companies back under oversight, or living with the kind of “light-to-little touch” regulatory approach favored by the Trump Administration and its regulatory agencies. Whatever deal emerges between AT&T and the Trump Administration’s FTC will likely be “win-win” for the company and the regulator, with consumers offered only token relief.

The goals likely to be achieved in any settlement:

- AT&T would clearly like to avoid a $100 million fine and other enforcement actions, so agreeing to ease throttling (something it has done already) and better disclose the practice would hardly create a problem for the company, especially if fines are dropped as a result.

- The FCC’s new “net neutrality” policy depends almost entirely on effectively abdicating oversight responsibility to the FTC, something embarrassing and hard to justify if AT&T managed to permanently bar the agency from regulating the company.

- The FTC can claim victory by telling consumers they are watching ISPs for undisclosed and unwarranted throttling, without opening up new legal challenges by outright banning of the practice, heavily fining violators, or collecting damages on behalf of customers victimized by prior bad acts.

Subscribe

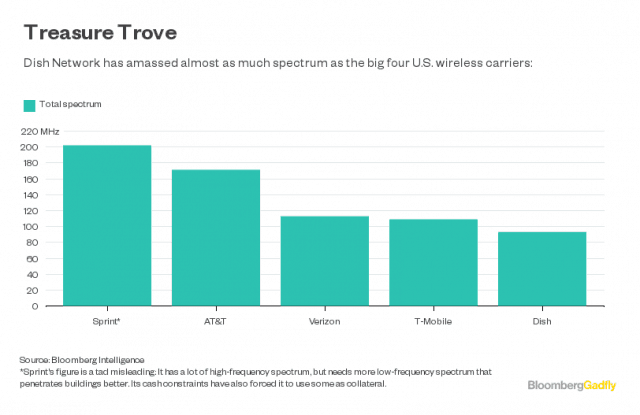

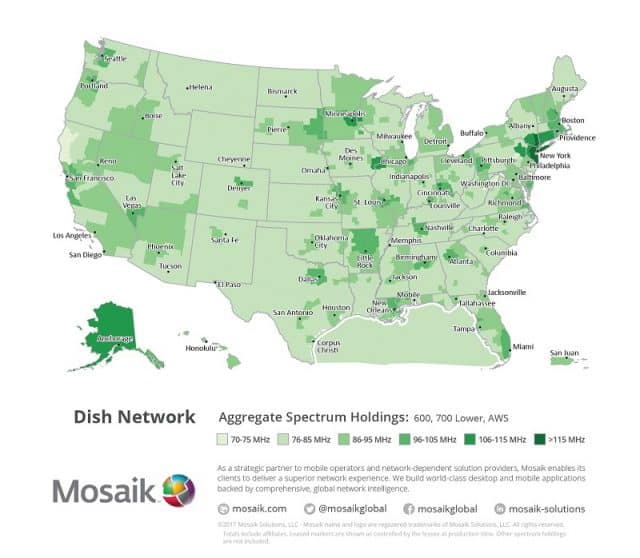

Subscribe Among the major wireless companies with spectrum holdings worth billions, few would suspect that the fifth largest (behind Sprint, AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile) is the satellite television company Dish Networks.

Among the major wireless companies with spectrum holdings worth billions, few would suspect that the fifth largest (behind Sprint, AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile) is the satellite television company Dish Networks. Because time and money is on the line, Dish needs to either build its network quickly or

Because time and money is on the line, Dish needs to either build its network quickly or

AT&T does not see fixed wireless millimeter wave broadband in your future if you live in or around a major city.

AT&T does not see fixed wireless millimeter wave broadband in your future if you live in or around a major city.

Cable and satellite companies are notorious for baiting customers with cheap offers for internet, phone, and television service and then shocking them when the first much-higher-than-expected bill arrives, but Altice’s Optimum/Cablevision takes the bait and switch promotion to a whole new level.

Cable and satellite companies are notorious for baiting customers with cheap offers for internet, phone, and television service and then shocking them when the first much-higher-than-expected bill arrives, but Altice’s Optimum/Cablevision takes the bait and switch promotion to a whole new level. Comcast customers receiving inadequate Wi-Fi coverage while using a company-provided wireless gateway can now buy a mesh-style wireless solution starting at $119.

Comcast customers receiving inadequate Wi-Fi coverage while using a company-provided wireless gateway can now buy a mesh-style wireless solution starting at $119.