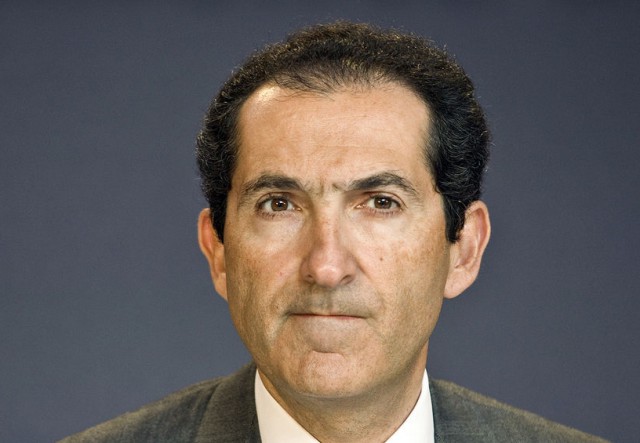

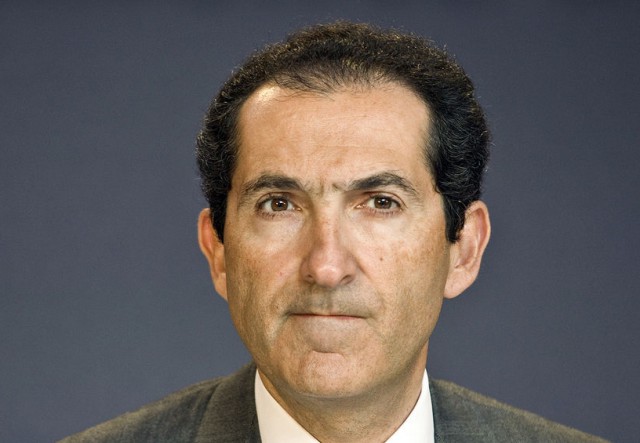

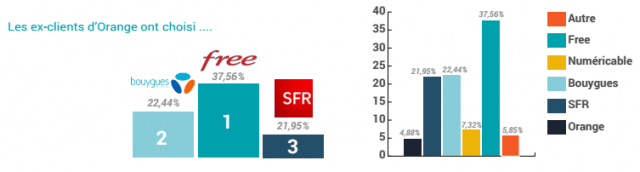

THE FRENCH SLASHER: Patrick Drahi’s cost-cutting methods have caused an uproar in France, leading nearly two million customers to flee his telecom companies for other providers.

Even as Patrick Drahi’s Altice promises state regulators expensive upgrades and better service for Cablevision subscribers in return for permission to buy the cable operator, complaints from Altice customers in France are now achieving an unprecedented high, with French media reports implicating Drahi’s demands for severe cost cutting in disastrous consequences for customers that face service outages that can last weeks.

SFR, one of France’s largest telecom service providers, has been the subject of ongoing media attention across France as customers continue to complain about promised network improvements that have ground to a halt, deteriorating infrastructure and service outages, poor customer service, and what French telecom experts claim is a clear case of cost-cutting being given precedence over good service.

Rarely has a company executive charged with putting a company’s case to the media and the public had a more difficult time explaining away the thousands of complaints that media outlets receive when they ask readers and viewers to comment about Altice-owned companies.

Salvatore Tuttolomondo, a regional director of relations for SFR, could only muster, “For now, we are not very good, but we are not bad,” in defense.

The French Association of Telecom Users (AFUTT) reports complaints about what is now one of the worst-performing telecom providers in France have exploded. SFR has seen a doubling of complaints from its wired customers between 2014 and 2015 and complaints about wireless service are also up by 50%.

“Even Free.fr and MVNOs do better,” says Denis Leboeuf, from the AFUTT.

For many French consumers, Altice teaches the lesson of bewaring promises of vast service improvements from an executive with a well-known demand to cut costs to the bone.

Capital reports the reason for SFR’s troubles is easy to identify.

Subscriber Numbers Falling…

“To restore margins, the operator has sacrificed the quality of its network and its customer service,” the magazine reports.

Capital lays out an indictment of Drahi’s way of doing business, one that has occasionally left his customers in peril when they were unable to summon emergency assistance over failing telephone lines or ruined one town’s tourist season when service problems made it difficult to impossible for visitors to register for events and arrange bookings.

It was never supposed to happen this way. On April 7, 2014, a triumphant Patrick Drahi announced his company Altice trumped rivals like Bouygues Telecom to acquire SFR from French conglomerate Vivendi for about $17 billion dollars. The first thing Mr. Drahi promised was to invest heavily in SFR to improve network quality and cut unnecessary costs. Those promises are now familiar to Cablevision subscribers as regulators in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey contemplate approving the sale of the cable company to Altice.

Much of France is still waiting for those promised upgrades. SFR’s DSL equipment is ‘downright lousy,’ delivering dead last performance among French telecom operators. SFR wireless data is no prize either, with customers howling complaints about slow to unresponsive service. Even texting over SFR’s network is dreadful, reports La Voix du Nord: “Carrier pigeons are faster,” it reported. Widespread complaints of texting failures lasting hours are legion. Customers know when service is restored when the dozens of unanswered texts they didn’t receive during the business day suddenly arrive in the middle of the night.

…While complaints are rising.

One nurse discovered her best bet is to go and stand near her toilet, where cell reception is just good enough to roam on a cell network operating across the border in Belgium. Other customers have to go outside to find a signal, because many of SFR’s cell towers are often affected by service interruptions which can last weeks.

Several French cities were the unlucky recipients of SFR service outages in December. Parts of Pas-de-Calais had the displeasure of being “cut off from the world” by a complete service outage lasting 15 days. French businesses sent employees to coffee shops and other venues during the business day with their cell phones to find a wireless signal to conduct business for more than two weeks.

La Voix du Nord confirmed one subscriber’s account that The Grand Wireless Failure of 2015 in Desvres came as a result of an antenna that fell into disrepair. The problem was identified in the first week of December, but an employee-engineer brusquely admitted “maintenance [to restore service] will not take place before Wednesday, Dec. 16” — at least two weeks later. Whether the repair could be completed quickly or not made no difference. Cost controls at SFR controlled the calendar.

French telecom watchdog ARCEP has learned to take Altice’s promises and commitments with a grain of salt. It suggested the “gap between promises and reality” had grown into a chasm over SFR’s appallingly awful 3G service. Altice replied it was “undertaking a major renovation program of its mobile network that is not without impact on service quality, but it is an investment for the next 15 years.”

Waiting on hold

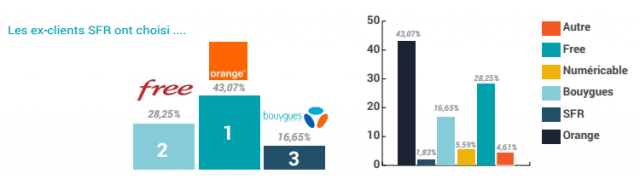

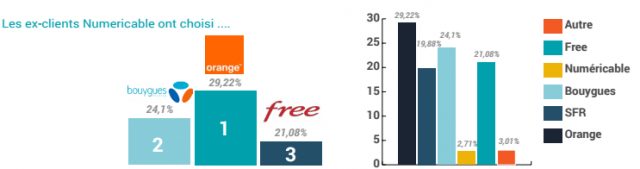

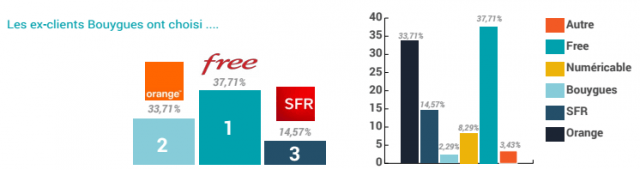

More than a few customers wonder if that means it will take 15 years to get reasonable service. More than 1.6 million so far have decided not to wait and find out.

Laurence joined the exodus of customers canceling service this month. Many customers leave angry, such as the parade of residents from the “digital eco-district” of Issy-les-Moulineaux who are “exasperated by repeated failures” of SFR’s wired broadband and television service equipment. Of the 40 days Laurence was a customer, he lacked Internet service for 17 of them.

Altice officials call the horror stories anecdotal and note they have millions of happy customers. But La Voix du Nord isn’t so certain that is true either. (They are also an SFR customer suffering service problems.) Since Drahi took over as the new owner, the newspaper surveyed its readers starting in March 2015 for their thoughts about Altice-owned SFR. In less than 24 hours, their Facebook page melted down with 3,760 mostly critical responses. Orange, the cell phone company the French usually love to hate, skated by with ten times fewer complaints than SFR. Altice officials promised things were about to get much better in response.

Slightly.

Heading for the exit

Last fall, the newspaper repeated the survey and 2,700 comments and replies arrived, again overwhelmingly negative. More than 100 customers were so angry, they wanted to share details of their service tragedies in private messages. The reader service representative eventually had to ask people to stop, saying she had at least 100 more unread in her inbox.

Customers were promised upgrades before. Thomas Detrain of Nœux-les-Mines received word he should expect one disruption lasting three weeks back in November 2014. Since that time, the outages keep on coming and SFR has offered him one time compensation of approximately $44 on one bill amounting to about $52. SFR now expects to be paid in full, whether the service is working or not.

Charlotte Dabrowski of Bourbourg has had her problems with service quality, too. But at least she has some service. “What makes me the most pissed off is that I was told: ‘You’re lucky, you are on the right side of our antenna.’ Was this supposed to be funny?”

Tuttolomondo: You can’t trust our customers.

SFR has resolved to either downplay its legendary bad press or blame someone else for all the troubles.

Tuttolomondo attempts the former, dismissing the thousands of Facebook complaints the newspaper had received.

“You have how many comments from dissatisfied customers, 2,000?,” Tuttolomondo asked. “We have about 500,000 customers in the region, so this is less than 0.5%.”

When asked if SFR would automatically compensate customers for its significant service outages, Tuttolomondo implied his customers would take advantage of him if he tried.

“It’s case by case,” said Tuttolomondo. “I’m not going to promise a general compensation, otherwise even customers who do not have to worry will ask me for money. But our customer service is really alert. You think it makes me happy to have unhappy customers? We’ll never get 100% satisfied.”

Tuttolomondo also seemed exasperated with his own customers, implying the company’s poorly rated 4G service “sometimes comes from incompatible phones” owned by customers who didn’t know better.

SFR’s customer service call center… in Tunisia.

Tuttolomondo’s line matches that of SFR’s customer service representatives, now relocated to call centers sprinkled across the exotic North African desert lands of the Maghreb, where workers with passable French language skills are willing to work cheap. But not cheap enough. Recently Drahi has been looking for an even better deal from subcontractors in Portugal, Mauritius and Madagascar. Customers lament it will probably be difficult to get a call center employee living with a few hours of electricity a day and no telephone service at home to comprehend why SFR’s fiber to the home service is not meeting its broadband speed objectives.

Drahi yes-man Jerome Yomtov, the Deputy Secretary General of SFR, decided it would be more productive to blame someone else for everything — Vivendi, the former owner, in particular.

“For our 3G and 4G networks, we pay the price of under-investment from the previous [owner],” explains Yomtov. He added the sale disrupted upgrades for two years. SFR had reduced its investments by 10% after it knew it was going to be put up for sale. But Capital reports after Drahi arrived, investments froze almost completely, which caused ever-increasing delays for network repairs and upgrades to keep up with traffic demands, not to mention commissioning new cell sites to improve coverage.

The reason for the delay was a Drahi-inspired Lord of the Flies-style bidding war among vendors and subcontractors.

Altice Cost Cutters: It was either this…

“The new management has replaced our usual subcontractor bidding process with that used by Numericable [another Drahi-owned company],” a network technician tells Capital. The result was endlessly repeated bidding rounds as subcontractors tried to undercut each other to win Drahi’s business. The technician reports Drahi allowed the bidding to run up to four months, resulting in one of the last rounds to scrape together a bid offering savings of just 5,000 Euros (just over $5,000) over a previous round.

“Drahi wanted to see how far they would be willing to come down,” the technician said. “The standoff would have [eventually] enabled SFR to save 10-15% of its infrastructure costs.” In the end, the priority given to cost-savings (at the cost of deteriorating service) caused a stagnancy of upgrades lasting almost nine months, claimed one project manager.

ARCEP revealed that SFR now has France’s smallest high-speed 4G network, with only 39% of the population covered. SFR officially claims 65% coverage, but that difference comes largely from coverage rented from competing Bouygues Telecom. Over the first 11 months of 2015, Altice’s subsidiary has managed to launch only 962 new antennas, three times less than the notoriously cheap Free.fr.

More stories of Altice’s so-called “Cost-Killing Madmen” — the company’s bean counters sent in after Drahi closes on a deal — have also since emerged. Employees tell the French press their cost-cutting schemes are bizarre and ruthless. Employees in one office were suddenly given orders to discard the office’s plants strategically placed to help improve the working environment.

“They told us it’s that or the toilet paper,” sighed the employee. Many thought the cost-cutters were joking at first, until they remained stone-faced during the nervous laughter shared by employees.

…or this

At the headquarters of La Plaine Saint-Denis, visitors may notice things are looking a little worse for wear in the office. That may be because the carpet is no longer cleaned weekly. The bean counters think once every two weeks is enough. But the toughest conditions are now probably experienced by the janitorial staff, who have been ordered to clean and maintain 46 office restrooms and given only three hours each work cycle to complete the task. At least 700 workers in Lyon were denied doctor visits for several days when the cost-cutters decided medical expenses were too high. It took the Works Council a few angry moments with company executives to rescind that budget cut.

Despite the plight of the workers, Drahi has some headaches of his own. He is hard at work conquering the most exclusive neighborhood in Geneva, Switzerland. Drahi, who boasts about his cost cutting and his ability to pay minimal wages, has splurged on two enormous villas in the commune of Cologny. His deputies and financial partners are not far away, having spent small fortunes on expensive housing in Vésenaz and Prangins. Now one of Drahi’s protegés, Jean-Luc Berrebi, member of the board and chief financial officer at Altice-owned Israeli telecom company HOT, has strategically moved himself right next door to Drahi, spending nearly $28 million dollars to buy Drahi’s second villa just 100 meters away. At the same time Drahi was closing on that deal, ordinary Israelis are shelling out considerably more for service from HOT, after the company announced sweeping rate hikes.

Exempt from cost-cutting: One of two Drahi villas in Switzerland, recently sold to a protegé for about $28 million. Drahi still lives next door.

Investors initially seemed pleased to learn cost cutting and reduced investment helped SFR increase its margin 18% since the beginning of 2015, which has allowed the company to deliver some impressive results to shareholders, at least in the short-term. But that good news was tempered by the veritable stampede of customers fleeing SFR for better service from other providers. Many in the French media now question whether Drahi has not just damaged SFR’s service, but also permanently tainted the image of its brand.

Executives at Orange can sigh some relief watching the chaos unfold at SFR and Numericable. Customers that swore off Orange with protestations of “never again,” are now increasingly calling the perennial bad boy of wireless “the lesser evil.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Patrick Drahi’s Altice — new owner of Suddenlink and presumed next owner of Cablevision —

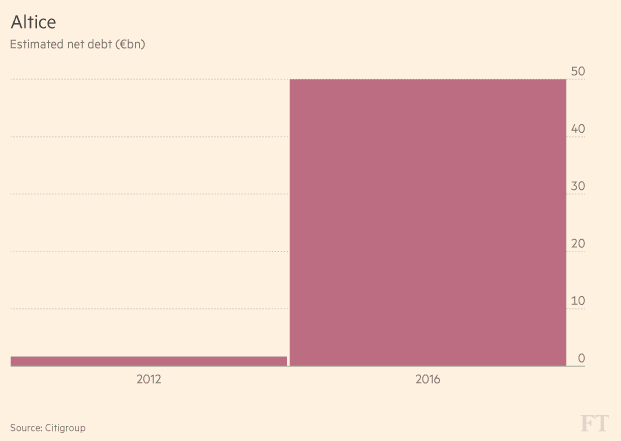

Patrick Drahi’s Altice — new owner of Suddenlink and presumed next owner of Cablevision —  The company’s massive debt load also continues to be a major concern. This week, Altice

The company’s massive debt load also continues to be a major concern. This week, Altice

Billionaire cable magnate and

Billionaire cable magnate and  Critics of the deal include consumer groups concerned about the poor performance of other Drahi-run cable systems and Cablevision’s organized labor force, unhappy about Drahi’s statements to Wall Street that he prefers to pay only minimum wage wherever possible. Drahi also has a long contentious history with Altice workers in Europe, presiding over workforce reductions, salary and benefits cuts, and a war of attrition with his own suppliers.

Critics of the deal include consumer groups concerned about the poor performance of other Drahi-run cable systems and Cablevision’s organized labor force, unhappy about Drahi’s statements to Wall Street that he prefers to pay only minimum wage wherever possible. Drahi also has a long contentious history with Altice workers in Europe, presiding over workforce reductions, salary and benefits cuts, and a war of attrition with his own suppliers.

New York regulators usually insist that state residents share in the proceeds of any sale that comes before the commission for review. In most cases, this is in the form of an agreement to invest in infrastructure or service improvements, improve customer service standards, and protect jobs. As with Time Warner Cable and Charter, the staff recommended the commission first consider a roughly 50/50 share of any deal savings or synergies, evenly split between customers and shareholders.

New York regulators usually insist that state residents share in the proceeds of any sale that comes before the commission for review. In most cases, this is in the form of an agreement to invest in infrastructure or service improvements, improve customer service standards, and protect jobs. As with Time Warner Cable and Charter, the staff recommended the commission first consider a roughly 50/50 share of any deal savings or synergies, evenly split between customers and shareholders. “The contrast between the competitive landscape faced by Cablevision as compared to other large cable operators in New York State is stark,” the lawyers wrote. “Verizon FiOS is available in just two Comcast communities, 3% of Time Warner Cable communities, and zero Charter communities in the state.”

“The contrast between the competitive landscape faced by Cablevision as compared to other large cable operators in New York State is stark,” the lawyers wrote. “Verizon FiOS is available in just two Comcast communities, 3% of Time Warner Cable communities, and zero Charter communities in the state.”

The Communications Workers of America has told the New York Public Service Commission it should reject Altice’s proposal to buy Cablevision for more than $17 billion, claiming it’s a bad deal for customers and employees alike.

The Communications Workers of America has told the New York Public Service Commission it should reject Altice’s proposal to buy Cablevision for more than $17 billion, claiming it’s a bad deal for customers and employees alike. “As late as the morning of Feb. 5, [the Joint Applicants] have continued their grudging and incomplete disgorgement of relevant and probative material to which CWA is entitled,” the CWA wrote. “CWA now possesses documents and data which are contradictory and require reconciliation.”

“As late as the morning of Feb. 5, [the Joint Applicants] have continued their grudging and incomplete disgorgement of relevant and probative material to which CWA is entitled,” the CWA wrote. “CWA now possesses documents and data which are contradictory and require reconciliation.” New York City’s Office of the Public Advocate is no fan either. In

New York City’s Office of the Public Advocate is no fan either. In