With taxpayer subsidies on the horizon, phone companies cut back investing their own money on rural broadband expansion hoping taxpayers would cover funding themselves.

That is the conclusion of Dave Burstein, a long-standing and well-respected industry observer and publisher of Net Policy News. Burstein is concerned the unintentional consequence of Obama and Trump Administration rural broadband funding programs has been fewer homes connected than what some carriers would have managed on their own without government subsidies.

“Since 2009, carrier investment in broadband in rural areas has gone down drastically,” Burstein wrote.

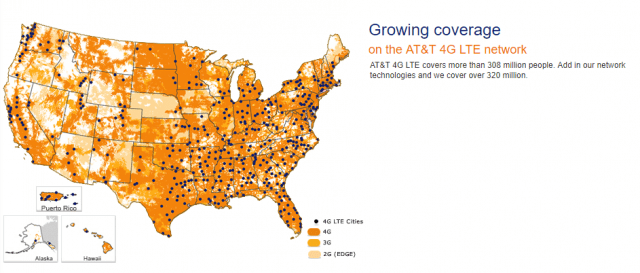

As a result, FCC Chairman Ajit Pai announced plans to spend $4.53 billion from a public-financed Mobility Fund over the next decade to advance 4G LTE service, primarily in rural areas that would not be served in the absence of government support. Burstein suspects much of that money could end up being unnecessarily wasted.

“Under current plans, most of the money is likely to go where telcos would build [4G] without a subsidy, [or will be used to] buy obsolete technology, or give the telcos two or three times what the job should cost,” Burstein wrote. “Any spending on wireless except where towers or backhaul is unavailable should be assumed wasteful until proven otherwise. Realistic costs need to be developed and subsidies allocated on that basis.”

AT&T’s rural fixed wireless expansion program, funded substantially by U.S. taxpayers and ratepayers, is a case in point. AT&T is receiving almost $428 million a year in public funds to extend wireless access to 1.1 million customers in 18 states, the FCC says. Much of that investment is claimed to be spent retrofitting and upgrading existing cell towers to support 4G LTE service. But AT&T claims 98% of its customers already have access to 4G LTE service — more than any other carrier in the country, so AT&T is actually spending the money to bolster its existing 4G LTE network, something more likely to benefit its cell customers, not a few thousand fixed wireless customers.

“An AT&T exec in California said communities didn’t need to worry about the impact of the CAF-funded project, since it was almost all going to be on existing towers,” Burstein wrote, allaying fears among members of the public that money would be spent on lots of new cell towers. “I don’t know what loophole AT&T is using to get the money, but it’s a pretty safe guess they would have upgraded most of them without the government paying. 4G service now reaches all but 3-5 million of the 110-126 million U.S. households. Probably half [of the less than five million] targeted would soon be served without a subsidy – if the telcos knew no subsidy was likely. Before spending a penny on subsidies, the FCC needs to do a thorough assessment of what would be built without government money.”

Wireless executives were delighted when the U.S. government in 2009 committed to spending $7 billion in taxpayer funds on broadband stimulus funding as part of a full-scale economic stimulus program to combat the Great Recession.

“Both George Bush in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2008 had promised to bring affordable broadband to all Americans,” Burstein noted. “The clamor to reach these last few million was so loud, telcos became confident the government would pay for it if they just stopped their own investment. They aren’t stupid and refused to spend their own money. Before 2009 and the expected huge stimulus program, most telcos expanded their networks each year, based on available capital funds.”

Burstein believes some phone companies became better experts at milking government money to pay for needed network upgrades than frugally spending public funds on rural broadband expansion. As a result, after eight years and massive spending, Burstein notes fewer than two million of the “unserved” six million homes were reached by wireline or wireless broadband service when the funding ran out.

Under Chairman Pai’s latest round of rural broadband funding, Burstein believes much of this new money is also at risk of being wasted.

“[Pai] needs to dig into the details of what he’s proposing,” Burstein wrote. “Nearly all cells with decent backhaul will be upgraded to 4G; Verizon and AT&T have already reached 98% of homes. Government money should go to building towers and backhaul where that’s missing, not filling in network holes the carriers would likely cover.”

Rural advocacy groups have been frustrated for years watching rural telephone companies deliver piecemeal upgrades and service expansion, often to only a few hundred customers at any one time. When they learn how much was spent to extend broadband service to a relatively few number of customers, they are confused because companies often spend much less when they budget and pay for projects on their own without government subsidies.

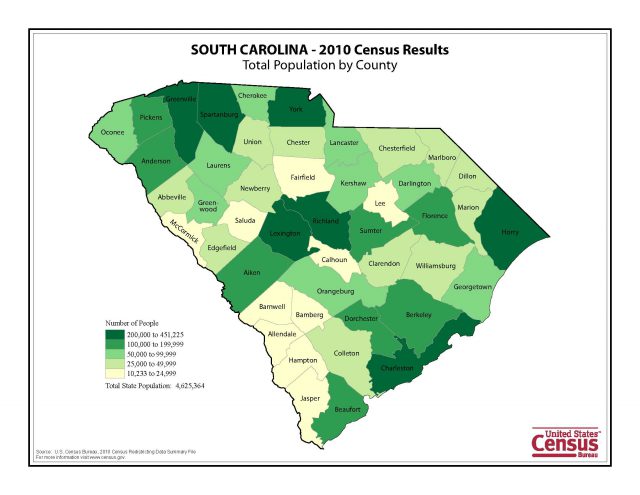

Burstein is currently suspicious about the $200 million approved in subsidy funding to extend rural broadband in parts of upstate New York. Burstein notes Pai is factually wrong about his claim that the hundreds of millions set aside for New York would be spent on “unserved areas of rural New York.”

“Most of that money will not go to unserved areas,” Burstein reports. “Some grants are going to politically connected groups. I’ve read the rules and the approved proposals. The amounts look excessive based on the limited public details.”

Telephone companies have become skilled negotiators when it comes to wiring their rural service areas. Most want more money than the government has previously been willing to offer to help them meet their Return On Investment expectations. Burstein noted that under normal circumstances, a government program offering a 25% subsidy to extend rural broadband into areas considered unprofitable to serve would be enough in most cases to get approval from rural phone companies like CenturyLink and Frontier Communications. But many phone companies, including AT&T, Verizon, and Qwest (now a part of CenturyLink) did not even file applications to participate in early funding rounds. Qwest’s lack of interest was especially problematic, because the former Baby Bell served the Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain regions where some of the worst broadband accessibility problems persisted.

Burstein claims Jonathan Adelstein, then Rural Utilities Administrator, had to double his subsidy offer to get Qwest’s attention with a 50% subsidy.

“Qwest refused, demanding 75%,” Burstein noted. “That was probably twice the amount necessary and Adelstein rightly refused. They knew the government had few ways to reach those unserved without paying whatever the telcos demanded. A few years later, Qwest is part of Centurylink. Many of those lines are now upgrading under [public] Connect America Funds with what amounts to a greater than 100% subsidy.”

Net Neutrality appeared to have no impact on telephone company investment decisions, even in rural areas. The investment cuts followed a trend that began even before President Barack Obama took office. Wireless carriers slash investments in rural areas when management is confident the government is motivated to step in and offer taxpayer dollars to expand rural broadband service. When those funds do become available, a significant percentage of the money isn’t spent on constructing new infrastructure to extend the reach of wired and wireless networks into unserved rural areas. Instead, it pays for expanding existing infrastructure that may coincidentally reach some rural customers, but is still primarily used by existing cellular customers.

“In many extreme rural areas, only the local telco has the ability to deliver broadband at a reasonable cost,” noted Burstein. “You need to have affordable backhaul and a local staff for repairs. Because the ‘unserved’ are in very small clusters, often less than 100 homes, it’s usually impractical for a new entrant to bring in a backhaul connection.”

Instead, AT&T is attempting to fill some of the gaps with fixed wireless service from existing cell towers. While good news for customers without access to cable or DSL broadband but do have adequate cellular coverage to subscribe to AT&T’s Fixed Wireless service, that is not much help for those in deeply rural areas where AT&T isn’t investing in additional cell towers to extend coverage. In effect, AT&T enjoys a win-win for itself — adding taxpayer-funded capacity to their existing 4G LTE networks at the same time it markets data-cap free access to its bandwidth-heavy online video services like DirecTV Now. That frees up capital and reduces costs for AT&T’s investors. But it also alienates AT&T’s competitors that recognize the additional network capacity available to AT&T also allows it to offer steep discounts on its DirecTV Now service exclusively for its own wireless customers.

Subscribe

Subscribe