New Zealand’s forthcoming transformation to fiber-based telecommunications infrastructure has some important lessons to teach those interested in improving broadband in North America.

New Zealand’s forthcoming transformation to fiber-based telecommunications infrastructure has some important lessons to teach those interested in improving broadband in North America.

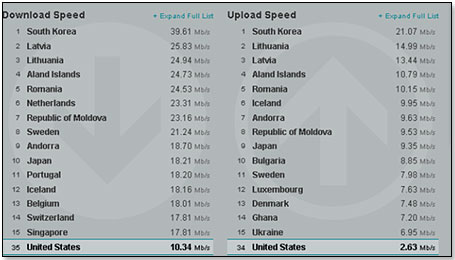

While Ottawa and Washington depend on the private sector to deliver 21st century broadband, other countries are recognizing private providers alone may not be able to deliver the essential networks of the 21st century, especially in smaller communities and rural areas still bypassed by even 20th century broadband. For Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and beyond — government and the private sector are working together to deliver advanced fiber-optic-based networks that will likely power broadband for at least the next decade or more. More importantly, they are doing so on terms that best serve the interests of the public, not just a handful of shareholders and investment bankers.

Priority number one is getting advanced networks built. Marketplace realities, particularly in North America, constrain private companies from taking risks on fiber networks that will take more than a few years to realize a healthy return on investment. Without that essentially-guaranteed payback, many providers refuse to think in terms of “revolutionary” broadband, relying on incremental “evolutionary” upgrades instead. That formula has also allowed many providers to ignore rural America, deemed too costly to wire.

In a country like New Zealand, these rules also apply, but in spades. Not only do Kiwis face a broadband experience that resembles service offered in the U.S. a decade ago, they are also punished by a lack of international capacity. With just one international provider delivering nearly all of New Zealand’s connectivity with the United States and beyond, prices are high and data caps are low.

Domestically, many Kiwis have traditionally had just one realistic choice for broadband service — Telecom New Zealand’s DSL technology. Although competitors have been allowed to resell DSL service over Telecom’s network, the limitations of the technology remain a constant problem for every provider on that network.

New Zealand has decided the best way to handle these challenges is to transform the telecommunications foundation across the country, starting with a new public-private fiber broadband network. NZ’s National Broadband Plan, dubbed “Ultra Fast Broadband,” establishes as its foundation the principle that broadband is too important to allow the country to languish waiting for private providers to step up.

Rosalie Nelson from IDC – the independent market intelligence advisory service, explores the pro’s and con’s of a nationwide fiber network for New Zealand. But it’s a lesson not just applicable to broadband in the South Pacific. Stop the Cap! is sharing this video seminar with our own Viewer’s Guide to help draw parallels to broadband closer to home. As an added bonus, you will come to understand different broadband technologies we regularly discuss.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/IDC Ultra Fast Broadband.flv[/flv]

IDC analyzes New Zealand’s new Ultra Fast Broadband — National Fiber Network in this seminar with Rosalie Nelson. It’s definitely a long view, but you will gain enormous insight into the challenges of delivering the next generation of broadband, not only in New Zealand, but in other countries around the world. (39 minutes)

Stop the Cap! Viewer’s Guide

To help draw comparisons with broadband in the South Pacific with that in the United States and Canada, we bring you this viewer’s guide to follow as you watch.

Part One

Nelson

In part one, Nelson explores the recent history of telecommunications in New Zealand, particularly focused on Telecom New Zealand, created from the former state monopoly for landlines and data circuits. Although the company began to open its network to competitors several years ago, the biggest transformation came in the last few years. New Zealand experienced its own version of the Bell System breakup, only this time that transformation came from the New Zealand government, not the courts.

When complete, what was once a single company became three — one for wholesale access, namely by independent competitors reselling service over Telecom lines, retail — the public face of the company that continues to market service under the Telecom brand to consumers and businesses, and Chorus, the entity that maintains Telecom’s infrastructure.

In North America, the equivalent would be the breakup of AT&T or Bell, with competitors allowed to lease access to their respective networks at prices and terms that could not favor either parent company.

While the debate rages over whether broadband expansion came as a result of Telecom’s breakup, or in spite of it, one thing everyone agrees on: New Zealand is one of the fastest growing broadband markets in the OECD, with a growth rate of nearly 35 percent every two years.

New Zealand’s telecom market is perhaps five or more years behind the United States and Canada. The rapid erosion of landlines for mobile or Voice Over IP service is only just starting in New Zealand. Telecom, like many phone companies in North America, still depends on the enormous pool of revenue landline service provides. Even as landlines decline domestically, phone companies like AT&T, Bell, Telus, Verizon, Frontier, and CenturyLink still treat this revenue as the critical foundation on which other products and services can be offered. It will be years before this base revenue erodes to the point of irrelevance.

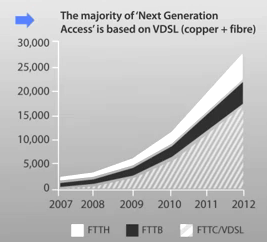

In Western Europe, VDSL has a significant head start in delivering next generation broadband. Similar to AT&T's U-verse or Bell's Fibe network, this technology delivers fiber to the neighborhood, but relies on traditional existing copper wire phone lines to reach individual subscribers.

Telecom is also highly involved in the mobile market. Just as in North America, when we talk about industry investment in networks, wireless is usually the largest recipient, sometimes at the expense of the landline network.

IDC, which is independently analyzing New Zealand’s forthcoming transformation to a fiber-based network, is excited about the transformational aspects of such a network, and recognizes public investment may be the only way to execute its rollout in a world where short term results and recouped investment can make all the difference between a green light and a red one among private providers.

Part Two (begins at 7:30)

In the second part of the video, Nelson succinctly explains some of the different technologies we talk about regularly on Stop the Cap!

For instance, most telephone and cable companies both use fiber cables for at least part of their network. Telephone companies like Frontier use fiber between their headquarters, local exchanges (a/k/a central offices), and occasionally even to remote exchanges, used to reduce the amount of copper wire between your home or office and their exchange. Many phone companies, including AT&T, use what Nelson calls “cabinets” to contain the interface between fiber and copper networks.

These are often dubbed lawn refrigerators — big four foot metal boxes installed on top of a concrete slab or attached to the side of a telephone pole. On one end, fiber optic cable from the central office arrives. On the other, individual copper wire lines exit, connecting to every customer up and down the street throughout the neighborhood. With additional fiber, phone companies selling DSL Internet access can increase speeds and offer service where it was not available before. AT&T can use a more advanced form of DSL as a platform for its U-verse service. Bell’s Fibe service in Canada is another example of this technology in use. CenturyLink is also deploying it for some of their service areas.

Cable companies use fiber to deliver their signals out to individual towns and parts of cities. From there, coaxial cable travels to homes and offices, on which we receive television, telephone, and broadband service. In large parts of Asia and Europe, cable television is much less common than it is in North America, so it’s a technology more unique to North America than to Europe or the Pacific.

Nelson also reminds us fiber is increasingly important for cell phone companies too, which use the technology to support the increasing amount of traffic that passes through cell towers. Fiber can help keep mobile broadband speeds at a reasonable level during peak usage periods. Where fiber isn’t available, the maximum amount of data that can travel between the cell tower back to the cell phone company’s data center can be significantly lower.

Nelson’s larger point is that there is a very real cost-benefit analysis to explore when considering whether the next generation broadband network should be 100% fiber-based, such as Verizon’s FiOS network, or a combination of fiber and more economical, already installed copper wire, such as AT&T’s U-verse. The initial expense of providing 100% fiber, direct to the home, is greater than repurposing part of our existing landline network. But with current technology, fiber can deliver a faster and more reliable level of service, and is future-proof. It also requires less maintenance once installed.

Part Three (begins at 16:20)

In the third part of the video, Nelson explores the political landscape in New Zealand, and with some minor differences here and there, the gap between the telecommunications market in Canada and New Zealand is not too different.

Xtra, the ISP owned by Telecom New Zealand, remains the country's largest service provider.

While the United States broke up the Bell System in the mid-1980s, Canada still relies heavily on behemoth Bell/BCE to deliver broadband access throughout the Atlantic provinces, Quebec, and Ontario. SaskTel and Telus deliver service to central and western Canada. Cable companies, primarily owned by Rogers, Shaw, and Videotron deliver service in major Canadian cities and nearby suburbs.

In New Zealand, Telecom was the former state-controlled monopoly telephone company. In recent years, that monopoly has been broken up, but broadband still relies heavily on Telecom’s landline network to deliver Internet access, primarily by DSL. In the past, Telecom was -the- Internet Service Provider. But now the company must sell access to their last mile network to all-comers at a regulated wholesale access rate. Canadians will recognize this kind of wholesale access policy — Bell has one for independent service providers to this day.

In the United States, things are a bit different. While there are instances of competitors providing DSL through landlines owned by familiar phone companies like AT&T, Verizon, CenturyLink, Frontier, and Windstream, very few customers know about them. Instead, cable television is the more familiar competitor, and the two players regularly beat each other up in marketing campaigns. If you ask an ordinary American consumer what companies sell broadband service, they will typically answer with the name of the telephone company and the cable company, if one serves their area. They are unlikely to answer Earthlink, which sells service over some telephone company and cable lines.

Some of Nelson’s anaysis about the changes in policy relating to the Ultra Fast Broadband network are no longer in effect with last week’s decision to abandon the “regulatory holiday” concept. The government’s original fiber network proposal has been modified repeatedly to fit into the business realities of the New Zealand ISP market. Some examples include recognizing the value and importance of the existing copper wire network, which will remain relevant in some rural areas not scheduled for wireless or fiber access — and will of course also be in operation as the fiber network is built. The government is also trying to promote private investment, and under pressure from large telecom companies, the government in power is looking for ways to assure investors of a return on their investment. Critics have charged the government leaned too far towards providers in effectively handing them at least eight years of monopoly service under a “regulatory holiday,” without oversight by the all-important Commerce Commission. A revised proposal seeks to guarantee investors a certain level of return, even if prices drop in the future, but retains regulatory oversight.

Big Phone Companies...

This policy is unique to New Zealand, and has not been tried in North America. Canada’s national broadband plan is long overdue and the one in the United States relies on some government stimulus money to incrementally expand broadband in unprofitable rural areas, but relies mostly on private providers for the bulk of the expansion. The Federal Communications Commission is exploring revamping its rural subsidy currently charged to every telephone line in the United States with the hope of diverting money to broadband development in rural areas. Private providers are expected to upgrade their networks through private investment for most of the rest.

New Zealand is proposing a totally new way of delivering broadband service with the establishment of an independent company responsible for the fiber network — a company not affiliated with any Internet Service Provider. That would make Telecom New Zealand no more or less important than any independent provider. Each ISP will succeed or fail based on price and value-added services, because the basic network experience is likely to be the same regardless of the provider selected. Some may deliver speed boosting features or sell content to customers. Others may deliver cheaper, slower speed plans for budget-minded customers. Some might even bundle free tablets or computers in return for fixed-length contracts.

But Nelson explains there is a risk. Once a fiber network is in place, it effectively becomes a utility, and it may or may not be able to earn sufficient revenue to embark on innovative new technologies that venture capital might otherwise afford. Because of market dynamics, for the same reason very few North Americans cities have more than one cable and one phone company, investors are unlikely to pour money into a competing technology if a fiber network is dominant.

...Often Think and Act Alike...

For a legacy phone company like Telecom, past regulatory requirements are also under review at the request of the telephone company. Telecom argues if a national fiber network is to be established, Telecom should be freed of its regulated responsibility to continue investing in its copper network, and the facilities used to support it.

This is similar to arguments AT&T and other phone companies have been making in their efforts to secure deregulation at the state level, for but different reasons. AT&T, as an example, argues that their aging copper wire network and its upkeep is a responsibility it agreed to in a different era, when landline service was ubiquitous and virtually everyone had a traditional phone line. Phone companies argue that as landline disconnections accelerate, the regulatory responsibilities assigned to it are no longer fair, and requires the company to continue investing capital in a network fewer and fewer customers are using. They argue investments would be more appropriately spent building next generation broadband and wireless networks.

AT&T might have a point, except for the collateral damage impacting rural customers, which AT&T may decide to abandon for the same reasons the company uses when it won’t provide broadband in rural areas — return on investment considerations. Those investments AT&T seeks to make would disproportionately benefit urban customers, at the expense of rural ones.

Part Four (begins at 29:15)

In the fourth part, Nelson explores the impact of the fiber project on Telecom, which is considering restructuring itself to compete under the new broadband model.

Nelson argues the company’s revenues are expected to be flat in the near future and predicts Telecom will be forced to begin a cost-cutting program, simplify its business, and target growth areas. Nelson ignores the most common strategies providers have used in this arena, however. In addition to job cuts, the other common way to increase revenue is to raise prices. Chorus, which administers Telecom’s broadband network, is the only real money maker inside Telecom these days, and that comes from broadband demand.

...Even When They Are Thousands of Miles Apart.

Nelson, like investors, opposes anything resembling a price war in New Zealand, one that could come as copper-based DSL providers slash prices to remain competitive with service on the much faster (but likely more expensive) fiber network. She sees such competition as a “war of attrition” where shareholder value is lost, along with incentives for further private investment.

Nelson’s final question ponders whether Telecom, still a dominant player in the New Zealand market, has the ability to change and adapt fast enough to the country’s fiber network.

Conversely, we wonder if Telecom will attempt to throw up roadblocks in an effort to curtail the new network as a defense strategy against those required changes to its business model.

We also wonder how much return on investment will be sufficient for investors. For some, anything short of “the sky is the limit” may fuel investment of a different kind — into special interest campaigns and lobbying to ensure there is no limit on the money they can earn from a network that could have a monopoly position in the marketplace.

Subscribe

Subscribe