Shammo

Verizon’s vision of broadband economics depends on the technology used to provide the service, according to some insights shared by the company’s chief financial officer at yesterday’s Deutsche Bank Access Media, Internet & Telecom Conference.

Fran Shammo outlined two strategies the company is using to profit from its broadband services. For wireless, Verizon has “flipped the model” from the traditional voice plan that starts with a bucket of voice minutes towards monetizing broadband usage instead. Today, customers buy plans that focus on anticipated data usage with unlimited voice and texting thrown in. But marketing broadband on Verizon’s fiber optic FiOS network is markedly different because the company is focused on speed over consumption.

“We are now shifting into concentrating on the broadband piece of that product, and the speed that the fiber to the home can give you we believe can’t be matched with anyone,” Shammo told an audience primarily made up of Wall Street analysts and investors. “We have a superior product.”

Shammo explained Verizon intends to “monetize speeds” that fiber broadband is capable of providing. That is important because Verizon FiOS now represents 70 percent of Verizon’s wired business, as traditional landline revenue continues to decline.

That is welcome news to broadband advocates that prefer current pricing models based on broadband speeds, not usage. Verizon FiOS intends to capitalize on its superior speed to differentiate itself from the cable competition, especially when some of those competitors are slapping usage limits on their customers.

Another important new revenue source for Verizon comes from switching legacy DSL users to FiOS technology.

In 2012, Verizon commenced its copper-to-fiber migration in FiOS areas. At least 200,000 homes formerly served by copper-based DSL were transitioned to fiber. In 2013, Verizon plans to migrate another 300,000 customers. When customers are switched to the fiber network, their former DSL speeds remain the same, but now Verizon’s marketing department has an opportunity to target upgrade offers for faster speeds.

“We give them the choice to start upgrading that speed [to] 15, 25, or 50Mbps,” Shammo reports. “What we are seeing is people are willing to pay for that additional speed, so we can monetize that fiber network more.”

However, Shammo reiterated that beyond what Verizon has already committed to in FiOS agreements with local municipalities, Verizon plans no additional expansion of FiOS in 2013.

The foundation for future profits come from data usage.

Unintended Consequences of Share Everything: Customers do an end run around Verizon’s “device fee.”

The conference also provided new insights into Verizon’s Share Everything wireless plans and the company’s other strategies.

Shammo admitted customers have done an end run around the “device fee” for multiple add-on devices.

Verizon expected mobile wireless-enabled tablet sales would increase as the cost to add a tablet to a Verizon Wireless account no longer required a separate data plan. But Verizon’s “device fee,” charged for each device connected to a Share Everything plan, has backfired. Customers are instead adopting Verizon’s “Mi-Fi” wireless hotspot device or other tethering solutions. Customers can then connect up to five Wi-Fi enabled devices through the hotspot and bypass paying multiple device fees that range from $5-20 per device.

Living Off the Revenue from a 3G Network Verizon Has Stopped Expanding, Improving

Shammo also noted Verizon has stopped further investments in its 3G wireless network.

“We are not investing any more capital in that network other than to keep it up and running, so no more coverage [expansion] capital, no more capacity [expansion] capital,” Shammo said. “If I can keep that network up and running that just generates more [revenue] for us.”

Verizon plans to keep a moratorium on further expansion of its fiber to the home service except in areas where it has existing agreements to deliver service.

Verizon’s Plans to Reduce Device Subsidies, Discounts

Customers have grown to expect a free or low-cost upgrade to a new smartphone every two years. But wireless companies find the costs of fronting device subsidies troubling because it affects the short-term bottom line. As wireless providers trim discounts, tighten upgrade policies, raise prices, and introduce new upgrade and activation fees, the $200-400 device subsidy recouped over the life of a two-year service contract remains a fat target for pruning.

But Verizon and other cell phone companies do not want to cut plan prices that are now inflated by $10-15 a month to cover paying back phone subsidies. The best of both worlds: eliminating device upgrade discounts –and– keeping prices the same for wireless service, banking the extra revenue as profit.

Verizon’s current solution is a middle-ground approach that gradually reduces device subsidies while hoping increased competition among device manufacturers will lower retail prices. For the consumer, that means prices will remain generally the same. But for Verizon, it means higher revenue from paying out lower subsidies while being able to maintain current pricing.

“I am a believer that over the next two to three years subsidies will start to decrease just because of the ecosystem,” said Shammo.

Verizon’s conversion to LTE means the day of a pure LTE-only smartphone is not far off. It will not include added-cost chips to support legacy technology, particularly older data networks and CDMA.

Wall Street Pressures Verizon to Talk Customers into Less-Costly (Anything but an iPhone) Smartphones

Brett Feldman, an analyst at Deutsche Bank who moderated the question and answer session with Shammo pointedly noted the Apple iPhone is the most-costly phone to subsidize.

“Are there things you can do with your sales force where you would proactively incentivize them to maybe sell different devices,” asked Feldman.

“It is critical that we don’t do that,” Shammo explained. “What is more important for us is a customer walks out with a phone that they will be happy with and not return under our 30-day guarantee. Because the worst thing that can happen for us is for me to incent a salesperson to get you into a phone thinking you are going to like and in three days you come back because you don’t. Now I’ve just subsidized two smartphones because that phone you used I can’t resell as a new phone.”

Subscribe

Subscribe

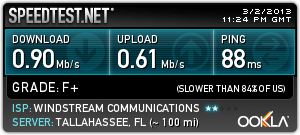

“I do not think it is ethical for companies like Windstream, already benefiting from taxpayer dollars, to back a bill that will keep municipalities from offering their residents something better,” said Creekmore.

“I do not think it is ethical for companies like Windstream, already benefiting from taxpayer dollars, to back a bill that will keep municipalities from offering their residents something better,” said Creekmore.

Alex Dudley, a specialist in corporate crisis communications, has left Time Warner Cable after serving as the cable company’s group vice president of public relations, to take an executive position at Charter Communications.

Alex Dudley, a specialist in corporate crisis communications, has left Time Warner Cable after serving as the cable company’s group vice president of public relations, to take an executive position at Charter Communications.