Phillip “Speaking as a Customer” Dampier

Two defenders of large Internet Service Providers are coming to the defense of the broadband industry by questioning a Guardian article that reported major Internet Service Providers were intentionally allowing a degradation in performance of Content Delivery Networks and other high volume Internet traffic in a dispute over money.

Richard Bennett and Dan Rayburn today both published articles attempting to discredit Battle for the Net’s effort highlighting the impact interconnection disputes can have on consumers.

Rayburn:

On Monday The Guardian ran a story with a headline stating that major Internet providers are slowing traffic speeds for thousands of consumers in North America. While that’s a title that’s going to get a lot of people’s attention, it’s not accurate. Even worse, other news outlets like Network World picked up on the story, re-hashed everything The Guardian said, but then mentioned they could not find the “study” that The Guardian is talking about. The reason they can’t find the report is because it does not exist.

[…] Even if The Guardian article was trying to use data collected via the BattlefortheNet website, they don’t understand what data is actually being collected. That data is specific to problems at interconnection points, not inside the last mile networks. So if there isn’t enough capacity at an interconnection point, saying ISPs are “slowing traffic speeds” is not accurate. No ISP is slowing down the speed of the consumers’ connection to the Internet as that all takes place inside the last mile, which is outside of the interconnection points. Even the Free Press isn’t quoted as saying ISPs are “slowing” down access speed, but rather access to enough capacity at connection points.

Bennett:

In summary, it appears that Battle for the Net may have cooked up some dubious tests to support their predetermined conclusion that ISPs are engaging in evil, extortionate behavior.

It may well be the case that they want to, but AT&T, Verizon, Charter Cable, Time Warner Cable, Brighthouse, and several others have merger business and spectrum auction business pending before the FCC. If they were manipulating customer experience in such a malicious way during the pendency of the their critical business, that would constitute executive ineptitude on an enormous scale. The alleged behavior doesn’t make customers stick around either.

I doubt the ISPs are stupid enough to do what the Guardian says they’re doing, and a careful examination of the available test data says that Battle for the Net is actually cooking the books. There is no way a long haul bandwidth and latency test says a thing about CDN performance. Now it could be that Battle for the Net has as a secret test that actually measures CDNs, but if so it’s certainly a well-kept one. Stay tuned.

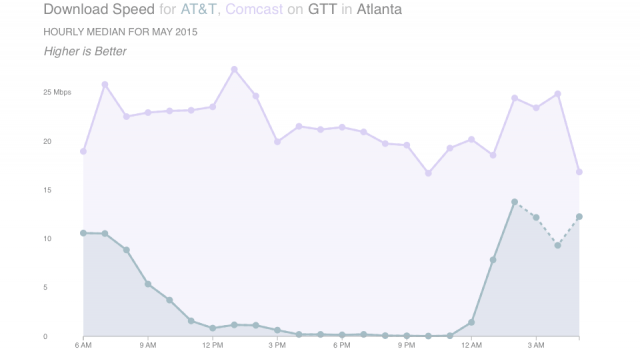

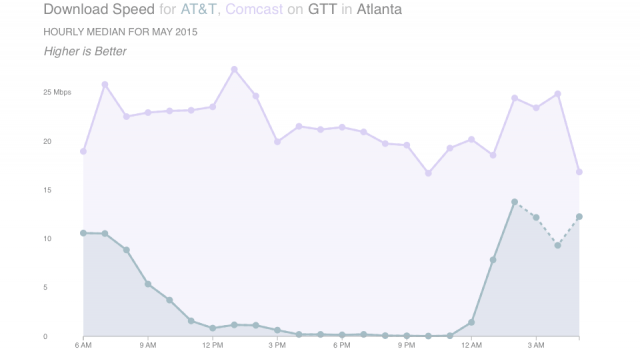

The higher line measures speeds received by Comcast customers connecting to websites handled by GTT in Atlanta. The lower line represents speeds endured by AT&T customers, as measured by MLab.

Stop the Cap! was peripherally mentioned in Rayburn’s piece because we originally referenced one of the affected providers as a Content Delivery Network (CDN). In fact, GTT is a Tier 1 IP Network, providing service to CDNs, among others — a point we made in a correction prompted by one of our readers yesterday.

Both Rayburn and Bennett scoff at Battle for the Net’s methodology, results, and conclusion your Internet Service Provider might care more about money than keeping customers satisfied with decent Internet speeds. Bennett alludes to the five groups backing the Battle for the Net campaign as “comrades” and Rayburn comes close to suggesting the Guardian piece represented journalistic malpractice.

Much was made of the missing “study” that the Guardian referenced in its original piece. Stop the Cap! told readers in our original story we did not have a copy to share either, but would update the story once it became available.

We published our own story because we were able to find, without much difficulty, plenty of raw data collected by MLab from consumers conducting voluntary Internet Health Tests, on which Battle for the Net drew its conclusions about network performance. A review of that data independently confirmed all the performance assertions made in the Guardian story, with or without a report. There are obvious and undeniable significant differences in performance between certain Internet Service Providers and traffic distribution networks like GTT.

So let’s take a closer look at the issues Rayburn and Bennett either dispute or attempt to explain away:

- MLab today confirmed there is a measurable and clear problem with ISPs serving around 75% of Americans that apparently involves under-provisioned interconnection capacity. That means the connection your ISP has with some content distributors is inadequate to handle the amount of traffic requested by customers. Some very large content distributors like Netflix increasingly use their own Content Delivery Networks, while others rely on third-party distributors to move that content for them. But the problem affects more than just high traffic video websites. If Stop the Cap! happens to reach you through one of these congested traffic networks and your ISP won’t upgrade that connection without compensation, not only will video traffic suffer slowdowns and buffering, but so will traffic from every other website, including ours, that happens to be sent through that same connection.

![MLab: "Customers of Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon all saw degraded performance [in NYC] during peak use hours when connecting across transit ISPs GTT and Tata. These patterns were most dramatic for customers of Comcast and Verizon when connecting to GTT, with a low speed of near 1 Mbps during peak hours in May. None of the three experienced similar problems when connecting with other transit providers, such as Internap and Zayo, and Cablevision did not experience the same extent of problems."](https://stopthecap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GTT-tata-640x357.png)

MLab: “Customers of Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon all saw degraded performance [in NYC] during peak use hours when connecting across transit ISPs GTT and Tata. These patterns were most dramatic for customers of Comcast and Verizon when connecting to GTT, with a low-speed of near 1 Mbps during peak hours in May. None of the three experienced similar problems when connecting with other transit providers, such as Internap and Zayo, and Cablevision did not experience the same extent of problems.”

:

Our initial findings show persistent performance degradation experienced by customers of a number of major access ISPs across the United States during the first half of 2015. While the ISPs involved differ, the symptoms and patterns of degradation are similar to those detailed in last year’s Interconnections study: decreased download throughput, increased latency and increased packet loss compared to the performance through different access ISPs in the same region. In nearly all cases degradation was worse during peak use hours. In last year’s technical report, we found that peak-hour degradation was an indicator of under-provisioned interconnection capacity whose shortcomings are only felt when traffic grows beyond a certain threshold.

Patterns of degraded performance occurred across the United States, impacting customers of various access ISPs when connecting to measurement points hosted within a number of transit ISPs in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Many of these access-transit ISP pairs have not previously been available for study using M-Lab data. In September, 2014, several measurement points were added in transit networks across the United States, making it possible to measure more access-transit ISP interconnection points. It is important to note that while we are able to observe and record these episodes of performance degradation, nothing in the data allows us to draw conclusions about who is responsible for the performance degradation. We leave determining the underlying cause of the degradation to others, and focus solely on the data, which tells us about consumer conditions irrespective of cause.

Rayburn attempts to go to town highlighting MLab’s statement that the data does not allow it to draw conclusions about who is responsible for the traffic jam. But any effort to extend that to a broader conclusion the Guardian article is “bogus” is folly. MLab’s findings clearly state there is a problem affecting the consumer’s Internet experience. To be fair, Rayburn’s view generally accepts there are disputes involving interconnection agreements, but he defends the current system that requires IP networks sending more traffic than they return to pay the ISP for a better connection.

Rayburn’s website refers to him as “the voice of industry.”

- Rayburn comes to the debate with a different perspective than ours. Rayburn’s website highlights the fact he is the “voice of the industry.” He also helped launch the industry trade group Streaming Video Alliance, which counts Comcast as one of its members. Anyone able to afford the dues for sponsor/founding member ($25,000 annually); full member ($12,500); or supporting member ($5,500) can join.

Stop the Cap! unreservedly speaks only for consumers. In these disputes, paying customers are the undeniable collateral damage when Internet slowdowns occur and more than a few are frequently inconvenienced by congestion-related slowdowns.

It is our view that allowing paying customers to be caught in the middle of these disputes is a symptom of the monopoly/duopoly marketplace broadband providers enjoy. In any industry where competition demands a provider deliver an excellent customer experience, few would ever allow these kinds of disputes to alienate customers. In Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Chicago, for example, AT&T has evidently made a business decision to allow its connections with GTT to degrade to just a fraction of the performance achieved by other providers. Nothing else explains consistent slowdowns that have affected AT&T U-verse and DSL customers for months on end that involve GTT while Comcast customers experience none of those problems.

We also know why this is happening because AT&T and GTT have both confirmed it to Ars Technica, which covered this specific slowdown back in March. As is always the case about these disputes, it’s all about the money:

AT&T is seeking money from network operators and won’t upgrade capacity until it gets paid. Under its peering policy, AT&T demands payment when a network sends more than twice as much traffic as it receives.

“Some providers are sending significantly more than twice as much traffic as they are receiving at specific interconnection points, which violates our peering policy that has been in place for years,” AT&T told Ars. “We are engaged in commercial-agreement discussions, as is typical in such situations, with several ISPs and Internet providers regarding this imbalanced traffic and possible solutions for augmenting capacity.”

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting.

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting.

In a more competitive marketplace, we believe no ISP would ever allow these disputes to impact paying subscribers, because a dissatisfied customer can cancel service and switch providers. That is much less likely if you are an AT&T DSL customer with no cable competition or if your only other choice cannot offer the Internet speed you need.

- Consolidating the telecommunications industry will only guarantee these problems will get worse. If AT&T is allowed to merge with DirecTV and expand Internet service to more customers in rural areas where cable broadband does not reach, does that not strengthen AT&T’s ability to further stonewall content providers? Of course it does. In fact, even a company the size of Netflix eventually relented and wrote a check to Comcast to clear up major congestion problems experienced by Comcast customers in 2014. Comcast could have solved the problem itself for the benefit of its paying customers, but refused. The day Netflix’s check arrived, problems with Netflix magically disappeared.

More mergers and more consolidation does not enhance competition. It entrenches big ISPs to play more aggressive hardball with content providers at the expense of consumers.

Even Rayburn concedes these disputes are “not about ‘fairness,’ it’s business,” he writes. “Some pay based on various business terms, others might not. There is no law against it, no rule that prohibits it.”

Battle for the Net’s point may be that there should be.

Comcast will challenge cord cutting and entice cord-nevers with an online video package of about a dozen television channels it will sell for $15 a month and likely exempt from its usage cap.

Comcast will challenge cord cutting and entice cord-nevers with an online video package of about a dozen television channels it will sell for $15 a month and likely exempt from its usage cap. Comcast will deliver Stream over the same network it uses for content delivery to game consoles that does not count against Comcast’s trialed usage caps. Watching competitor Sling TV does count against your Comcast usage allowance because it is delivered over the public Internet.

Comcast will deliver Stream over the same network it uses for content delivery to game consoles that does not count against Comcast’s trialed usage caps. Watching competitor Sling TV does count against your Comcast usage allowance because it is delivered over the public Internet.

Subscribe

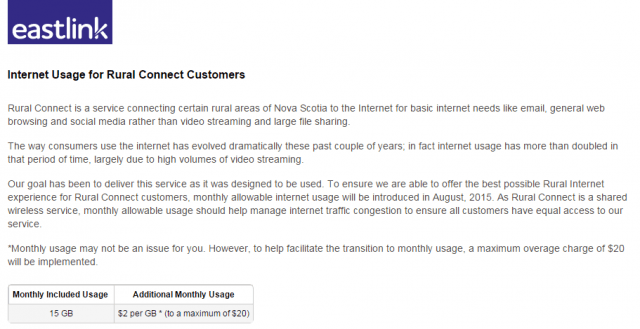

Subscribe A plan to place a 15GB monthly usage cap on Eastlink broadband service in rural Nova Scotia has led to calls to ban data caps, with a NDP Member of the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia leading the charge.

A plan to place a 15GB monthly usage cap on Eastlink broadband service in rural Nova Scotia has led to calls to ban data caps, with a NDP Member of the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia leading the charge.

Fournier suspects Eastlink has not invested enough to keep up with a growing Internet because the service originally advertised itself as a way to listen to online music and watch video. But he also wonders if the data cap is an attempt to force the government to fund additional upgrades to get Eastlink to back down.

Fournier suspects Eastlink has not invested enough to keep up with a growing Internet because the service originally advertised itself as a way to listen to online music and watch video. But he also wonders if the data cap is an attempt to force the government to fund additional upgrades to get Eastlink to back down.

![MLab: "Customers of Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and Verizon all saw degraded performance [in NYC] during peak use hours when connecting across transit ISPs GTT and Tata. These patterns were most dramatic for customers of Comcast and Verizon when connecting to GTT, with a low speed of near 1 Mbps during peak hours in May. None of the three experienced similar problems when connecting with other transit providers, such as Internap and Zayo, and Cablevision did not experience the same extent of problems."](https://stopthecap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GTT-tata-640x357.png)

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting.

Missing from this discussion are AT&T customers directly affected by slowdowns. AT&T’s attitude seems uninterested in the customer experience and the company feels safe stonewalling GTT until it gets a check in the mail. It matters less that AT&T customers have paid $40, 50, even 70 a month for high quality Internet service they are not getting. Customers paying $7.99 a month for what used to be called Hulu Plus will be able to add Showtime to their Hulu subscription for an extra $8.99 a month — two dollars less than what Showtime will charge Apple TV and other online video customers.

Customers paying $7.99 a month for what used to be called Hulu Plus will be able to add Showtime to their Hulu subscription for an extra $8.99 a month — two dollars less than what Showtime will charge Apple TV and other online video customers. Hulu customers who subscribe to Showtime will have access to every Showtime original series ever produced along with Showtime’s full catalog of the same movies, documentaries, specials and sports programming available to cable television customers. Hulu will also carry the east and west coast feeds of Showtime’s primary channel for those who want to watch live events.

Hulu customers who subscribe to Showtime will have access to every Showtime original series ever produced along with Showtime’s full catalog of the same movies, documentaries, specials and sports programming available to cable television customers. Hulu will also carry the east and west coast feeds of Showtime’s primary channel for those who want to watch live events.